With the world’s eyes on Europe during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, energy has become a big topic of conversation. Roughly a quarter of Europe’s oil and 40 percent of its natural gas comes from Russia. The Russian army has also seized Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, which is the largest in Europe.

European countries are developing plans to transform their energy grids as their long-standing reliance on fossil fuels becomes untenable—the escalation of decarbonization efforts are already underway. The European Union has announced it intends to cut Russian gas imports by as much as two-thirds by the end of this year. But when it comes to nuclear power’s role in the transition, nations remain split on what role it should or should not play. Roughly a quarter of Europe’s energy currently comes from nuclear power.

Jacopo Buongiorno, a professor of nuclear engineering at MIT, says the volatile energy source has long been a point of contention in Europe. Opinions on nuclear power, he adds, vary from government to government.

“It’s a checkerboard situation, in that there are some countries that are clearly negative about nuclear, others that are very positive, and also some newcomer countries that are seeking to develop a nuclear program for the first time,” Buongiorno says.

When it comes to countries that are against nuclear power, Buongiorno notes that Germany leads the way. The country decided to phase out its nuclear power plants after the Fukushima meltdown in 2011, and its three remaining plants will be shut down by the end of the year. The country is increasing its renewable energy capacity with new solar and wind facilities to try to make up for the loss of nuclear power.

“They remain steadfast that they don’t want nuclear,” Buongiorno says.

Spain intends to phase out its nuclear power plants by 2035. In 2017, Swiss citizens voted in favor of a referendum to start closing up their plants. Countries like Austria, Denmark and Portugal oppose nuclear power but don’t have any plants. Safety is a major concern across the board for these nations.

As for the pro-nuclear countries, the UK is a big supporter of nuclear power. The country has one nuclear plant under construction, and plans to build multiple new ones in the coming years. The Netherlands is planning on building at least two more nuclear power plants, and France is right with them with a goal to set up 15 new plants by 2050. Finland recently completed a large nuclear power plant that will soon be operational. Meanwhile, Buongiorno says most of Eastern Europe is also pro-nuclear.

“Either they already have it and want more, or they don’t have it and they want it,” he explains. Almost a quarter of Ukraine’s energy comes from nuclear power, for example.

[Related: In 5 seconds, this fusion reactor made enough energy to power a home for a day]

Buongiorno says nuclear power will be an important part of Europe’s transition off of Russian oil and gas—and the transition off of fossil fuels generally. However, there are some issues. As in the US, the construction of nuclear plants has faced significant problems. New projects regularly encounter long delays and significant cost overruns—only one has been completed in the states in the past few years.

“The industry must show that they can deliver new nuclear plants on time and on budget. In the past 10 years, they have not been able to do it,” Buongiorno says. He says a lot of plants end up costing around three times what was promised, and taking longer than a decade to finish.

Buongiorno says one of the main problems is that many of the companies have been focused on servicing, not new construction. Most of Europe’s plants, including Zaporizhzhia, were completed in the late 1980s. He adds that these companies don’t have good project management practices, and that there could be supply chain issue due to the long pause in building new reactors.

“The industry has definitely got to change to make it happen,” Buongiorno says.

Michael Mann, a climate scientist at Penn State, says he’s “skeptical” about Europe’s focus on nuclear power for its energy transition. He says existing plants should be kept running, but building out more nuclear power won’t solve the continent’s problems in an acceptable amount of time.

“It is not plausible that new nuclear construction … could possibly receive the short-term demand on energy caused by the present crisis,” Mann says.

[Related: Why Los Alamos lab is working on the tricky task of creating new plutonium cores]

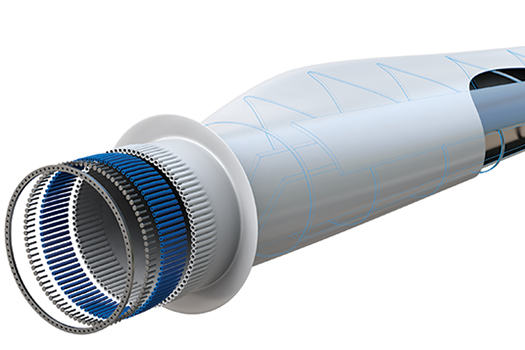

One way for Europe to bring on more nuclear power without such high costs and delays would be with small modular nuclear reactors. As the name implies, these reactors would be as much as 90 percent smaller than traditional ones, could be relocated if needed, and should be easier and cheaper to build overall. However, the designs are all still in the development phase, so they’re not ready to be deployed yet. In the states, only the company called NuScale has received design approval from the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

As much countries want it, it’s clear it’s not going to be easy for Europe to quit Russian oil and gas as quickly , Buongiorno says. It’s going to be a process that will take time and large investments.

“Nobody can snap their fingers and replace 40 percent of their gas overnight,” Buongiorno says. Energy transitions are exactly that, a transition—and that’s become especially true with nuclear power.