The barriers to individual invention are falling away. Amateur scientists and inventors now have access to tools exponentially more powerful and affordable than those a generation ago. They can transform ideas into physical products in a matter of days. And they can directly distribute those innovations—whether a new engine or an entirely new form of life—to a market of billions. The days of dreaming big are over and the era of doing big has just begun.

In March 1968, Stewart Brand, a Stanford University–trained biologist, ex-Army paratrooper and Ken Kesey–inspired Merry Prankster, was sitting on a plane, reading Barbara Ward’s Spaceship Earth, when an idea struck. He would assemble a catalog to connect back-to-the-landers, amateur inventors and proto-hackers with the tools they needed to change the world. If new tools make new practices, as Buckminster Fuller once noted, then better tools would make better practices. In the fall of that year, Brand mailed out the Whole Earth Catalog, a 65-page booklet filled with information about how and where to acquire shovels and seeds, designs for Japanese homes and one-man saw mills, even the world’s first personal computer. In the introduction, he wrote what has since become a rallying cry for a new generation of do-it-yourselfers: “We are as gods and might as well get good at it.”

In the 40 years since, we’ve gotten very good at it. DIY scientists and inventors are now using increasingly powerful tools to tackle challenges once reserved for governments and large corporations. They are delving into robotics, bioengineering, nanotechnology, manufacturing and aerospace design in the same way that hot-rodders in the 1950s remade their cars piece by painstaking piece. They are building unmanned aerial vehicles in their garages and creating customized lifeforms in their kitchens.

All of this came about as a result of one thing: computers. In 1958 Jack Kilby, an electrical engineer at Texas Instruments, developed the first integrated circuit. A few years later, Gordon Moore, while working at Fairchild Semiconductor, observed that the number of integrated-circuit components on a microchip tended to double every 12 months (he later revised the estimate to two years) while the cost per component fell sharply. Moore predicted that the exponential growth would continue “for at least 10 years.” He was right. It continued for 10 years, and then 10 more and continues today.

As computers got faster and cheaper, more people gained access to them and used them to make other digital tools, from microscopic sensors to giant data centers. Those tools, being digital, also became faster and cheaper. This feedback loop saw its most profound realization in the invention of the Internet (which, as it happens, took place right around the time that Stewart Brand was saying that we had become as gods). The Internet is not just a digital tool but a digital tool for communicating, and so communication is getting faster and cheaper—which finally means that innovation itself is accelerating at an exponential rate. More than two billion people are connected to the Web, and nearly any one of them can access most of the same sources a well-funded researcher can. They can receive expert advice on just about anything and outsource any job beyond their ken into a global supply chain of coders, developers, designers and parts manufacturers.

What people are doing with these new capabilities is nothing short of world-changing. In 2010, student bioengineers modified a bacteria to more efficiently remediate toxic waste from oil mining sites. Another student group recently developed bacteria that produce alkanes, the primary compounds in diesel fuel. Consider also the work done by Salman Khan. To help his younger cousins succeed in school, the former hedge fund analyst began posting video tutorials online. There are now more than 3,100 such tutorials, covering topics including basic algebra and advanced biology, and they are watched by more than six million visitors a month. Foldit, a crowdsourced game designed by researchers at the University of Washington, is another success story. The object of the game is to fold proteins, and anyone is free to play. Last year, over a period of three weeks, players determined the structure of an enzyme that could lead to the development of new AIDS drugs. This winter, other players found a way to increase, by 18 times, the rate of the Diels-Alder reaction, one of the most useful in organic chemistry.

The people making these advances are not experts—one of the world’s best protein folders is, by day, an executive secretary in a rehab clinic in Manchester, England. They are simply passionate individuals working to create a world in which abundance, not scarcity, is the norm. By following the seven steps starting here, you could join them.

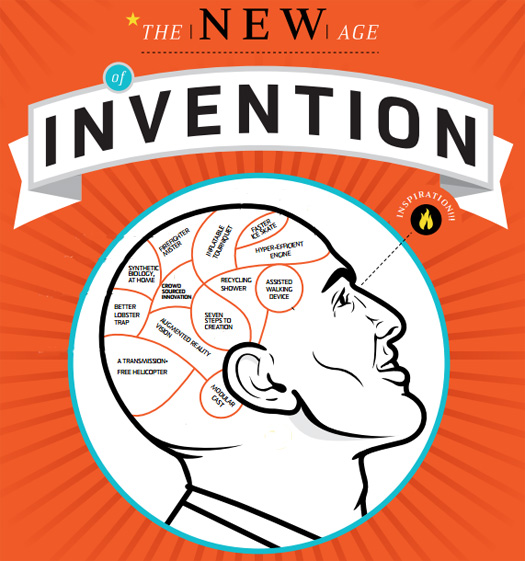

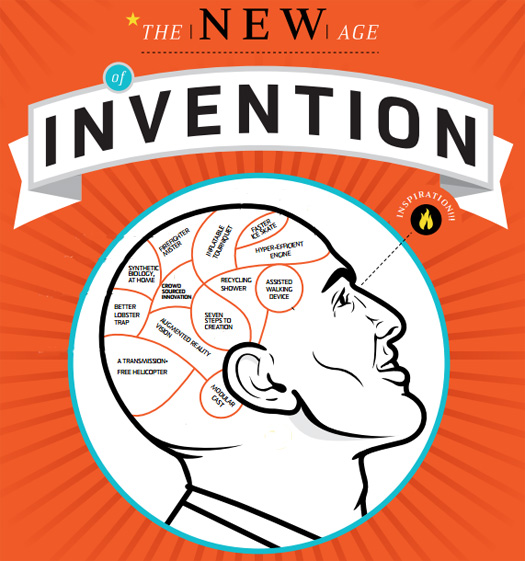

The Other 2012 Invention Awards Winners Are…

- A Spring-Loaded Ice Skate

- A Mister for Firefighters

- A Modular Cast

- An Assisted-Walking Device With Senses

- A Recirculating Shower

- A Higher-Efficiency, Lower-Emission Engine System

- An Inflatable Tourniquet

- A Better Lobster Trap

- A Simple Helicopter Engine

- Augmented-Reality Contact Lenses

- Where Are They Now? Winners From Past Years