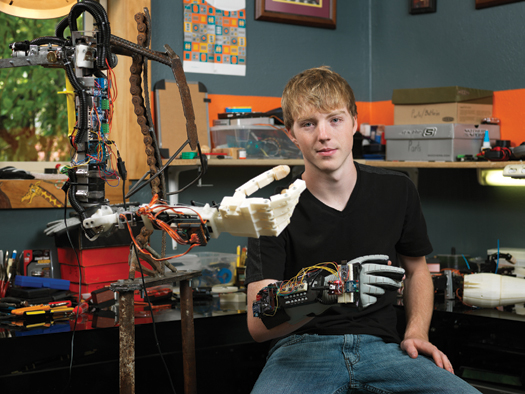

Late one night two years ago, Adam Munich found himself talking with two new acquaintances in a chatroom. One, a Pakistani guy, was complaining about rolling electricity blackouts in his country. The other had broken his leg in a motocross accident in Mexico and said his local hospital couldn’t find a working x-ray machine. The two situations fused in Munich’s mind; he wondered if a cheap, reliable, battery-powered x-ray machine existed—something that could be used in remote areas and function without being plugged in during blackouts. After discovering that the answer was no, he spent two years building one himself out of Nixie tubes, old art suitcases, chainsaw oil, and electronics from across the globe. It was an incredibly ambitious project for anyone, let alone a 15-year-old.

Munich started by reading online about the science of Coolidge tubes, the essential radiation-emitting core of most commercial machines, and eventually found one for sale from a manufacturer in China. “The rest was puzzle-solving,” Munich says. “For something like this, there’s no guide.”

He split the machine into two connected pieces: a control box that houses the electronics and a second case containing the x-ray tube and the high-voltage components that drive it. Batteries alone wouldn’t provide enough power. He needed a voltage multiplier, so he borrowed a design originally used in particle accelerators. When alternating current is applied, it flows into a charge-storing capacitor at its peak and then rushes through a charge-relaying diode when the polarity of the current reverses. This second burst of charge combines with the power stored in the capacitor, doubling the voltage. Using money he earned as a freelance Web designer, Munich bought enough capacitors and ultrafast diodes on eBay to link together four such setups. The voltage increases with each one until it reaches the 75,000 volts required to spark a decent beam of x-rays.

Munich, now 18, has used the machine to x-ray some household items, including a pen and a computer hard drive. Theoretically, he says, it could be used for hands or limbs. Now he is focused on getting the cost under $200 and making the device sturdy enough to help his friends from the late-night chat. But the current version is sure to help with a more immediate concern—impressing college admissions offices.

BUILDING AN X-RAY MACHINE

Time 2 years

Cost $700

See how Munich’s x-ray machine works on the next page.

HOW IT WORKS

Imaging: Inside the x-ray tube, a high-voltage current sends electrons to a tungsten target. The electrons slam into atoms inside the target, lose energy, and emit x-rays. The x-rays then flash ahead and create a shadow image of the subject. Most machines use flat-panel radiation detectors to get these pictures, but they cost about $65,000. Instead Munich bought a scintillation screen, a plastic sheet that turns fluorescent green when it’s hit with ionizing radiation.

Safety: Munich built his own Geiger counter to measure the radiation. The volume of x-rays coming out of the tube was in line with his estimates, and he found that the backscatter, or amount of radiation elsewhere, was very low. Still, he only uses it outside, aiming it at the woods behind his house. Otherwise some of the x-rays could bounce off an interior wall. He also added a speaker that emits a warning buzz when the machine is generating x-rays.

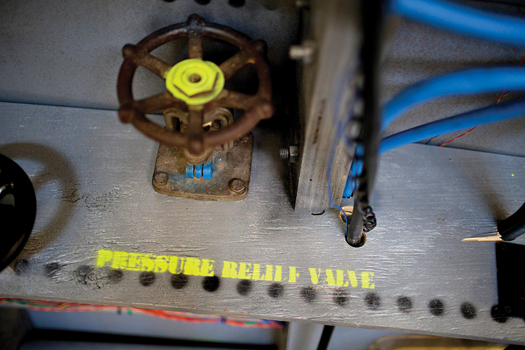

Insulation: Munich placed the high-voltage components and the x-ray tube in a plastic junction box filled with chainsaw oil. He tested the oil’s insulating capacity by dunking two metal plates in it and then sending increasing amounts of current into one. It took 100,000 volts for the charge to move through the oil from one plate to the other. Since the machine uses only 75,000 volts, the oil prevents the voltage from burning through the junction box or other parts.

Design: Matching art suitcases, linked by cable, enclose the two pieces of the machine. Munich cut holes in the lid for an on/off switch, meters that monitor current and voltage, dials to set the exposure time, and a Nixie-tube display from a Ukrainian supplier that counts the exposure time down to the tenth of a second.