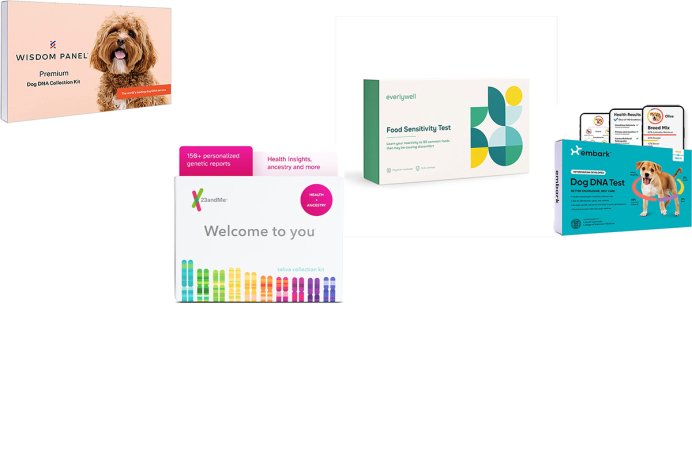

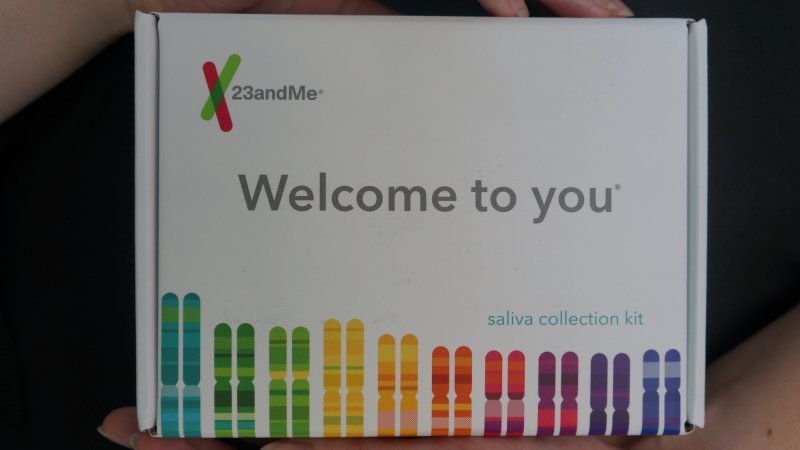

The Food & Drug Administration is finally allowing 23andMe to provide testing for the breast cancer-related genes BRCA1 and 2. Back in 2013, when the direct-to-consumer company originally starting selling the test, the FDA clamped down and forced 23andMe to verify its genetic health risk evaluations. 23andMe had to prove the genes they were testing for were related to a health condition, and show that the tests were accurate.

Now you’ll be able to buy your BRCA test online and get your results a few months later, all without ever seeing a genetic counselor or doctor. In some ways, this is a wonderful advent of technology. It democratizes health information. It empowers people to take control of their lives and mitigate risks.

But it also means we’re handing out data to people who might not be adequately prepared to hear it, and who might not actually understand what they’re getting. Testing positive for a genetic mutation often doesn’t mean you’ll get the associated disease, and we still don’t really understand how exactly genes impact your overall health. Before, when you had to get your genetic information through a counselor, a trained expert walked you through the process and explained the complex factors that go into disease risk. Now you get your answer from a website.

There’s a lot to unpack about this new BRCA test, so let’s take a few minutes to discuss what’s at stake here.

What is BRCA, anyway?

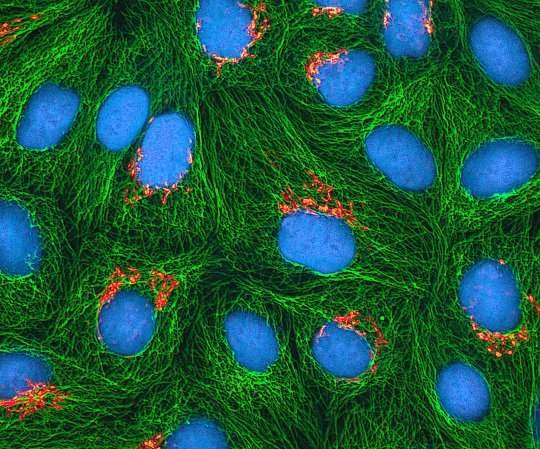

Inside your cells, you have a set of proteins whose only job is to identify and fix mistakes in your DNA. Every time your cells divide (which, by the way, happens millions of times a day), they have to replicate your genetic code to pass it along. Individual mutations—which is what we call any mistake in your DNA—happen all the time, but your repair proteins fix most of them before they cause any harm. Mutations most often come in the form of one DNA building block being swapped for another, but sometimes they occur because a DNA strand breaks, and the repair protein mends the strand imperfectly. Maybe a piece is lost, or the wrong end of the strand gets stuck back on. If just one strand snaps, the repair proteins can usually match the right end. But if both strands break at once, repair proteins struggle to make it right.

The BRCA1 and 2 genes produce some of these double-stranded DNA repair proteins. When they work normally, they can do the job pretty well. But if they have certain mutations, they stop being able to glue the broken DNA back together in the right orientation. This leads to a ton of glitches in the rest of your DNA, because the ends get stuck back in different spots. Cancer happens when you hit a critical mass of tumor-promoting mutations—tweaks that promote runaway growth—within a cell. So by increasing the odds and rates of mutations, faulty repair proteins can make you much more likely to develop cancer.

This is why the majority of women with BRCA1 and 2 mutations go on to develop breast cancer. In the general population, 12 percent of women develop the disease at some point in their life. But having certain BRCA1 or 2 mutations ups those odds to 72 and 69 percent, respectively. It also increases your chance of getting ovarian cancer, though not by nearly as much.

These mutations are inherited, so women with a strong family history of breast cancer—especially family members who got cancer in both breasts and/or at an early age—are often encouraged to get a genetic test. Being a carrier of these mutated genes doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll develop breast cancer, but it increases your odds so much that doctors tell people with positive results to get screened for cancer earlier and more often.

Does the 23andMe test work?

In order to get greenlit by the FDA, 23andMe had to prove that their test was clinically valid, meaning it can detects BRCA1/2 mutations with high accuracy and precision.

The big caveat here is that the 23andMe test only looks for three possible mutations out of more than 1,000 known variations. Not all of those are harmful, but many are, and the 23andMe test can’t tell you whether or not you have most of them. A negative result means you don’t have the three most common BRCA1/2 mutations, but you might have others.

It’s also worth noting that these three mutations are almost exclusively found in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Though you may have Jewish heritage that you’re unaware of, most people not of Ashkenazi descent are going to test negative through 23andMe regardless of whether or not they’re actually a carrier for other BRCA mutations.

Should I get the 23andMe BRCA test?

Very few physicians would recommend BRCA testing for the broad population. Less than one percent of people have a BRCA1/2 mutation, so screening everyone isn’t practical or ethical. You’d end up with a lot of false positives—meaning the test says you have a mutation, even though you don’t—because no test is 100 percent accurate. But it is often recommended that you get a test if you have a family history of breast cancer, or if a family member has a known BRCA mutation.

Before home DNA tests, you’d have to go to a genetic counselor to discuss whether you should get a BRCA test at all. The National Society for Genetic Counselors argues that this should still be the standard. “Anyone who has a strong personal or family history of breast or ovarian cancer and is interested in finding out more about their individualized risk should consult with a genetic counselor to discuss their genetic testing options, or to discuss their results,” said Erica Ramos, President of the NSGC, in a statement. Though it’s never a bad idea to go talk to a counselor, not everyone still agrees with that idea.

“I have become more open to the fact that not every person who gets BRCA testing needs a pre-emptive counseling session with a certified genetic counselor,” wrote Leonard Lichtenfeld, Deputy Chief Medical Officer for the American Cancer Society, on his official ACS blog. “Even the genetic counselors have told me they have better things to do with their time, and that there are acceptable alternatives to informing those who want to know more about the test before they get it, such as computer-based information modules.”

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which reviews evidence for various screening tests and offers a recommendation, says that women should first be screened for a family history of cancer and that “women with positive screening results should receive genetic counseling and, if indicated after counseling, BRCA testing.” They recommend against getting screened if you have no family history suggesting BRCA mutations.

“Given the importance of integrating medical and family history in understanding the implications of the results, it is similarly important that these be considered when deciding which tests are needed,” says Michael Watson, Executive Director of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. “Not only is it important to have knowledgeable professionals involved in interpreting the clinical implications of the results of these tests for a specific individual, it’s equally important that these knowledgeable professionals be involved in informing people of which test is most useful for them, if any.”

He notes that many of the other health conditions that direct-to-consumer tests look at don’t have a lot of clinical relevance. If you find out you’re predisposed to certain eye diseases, it probably won’t change what your doctor recommends you do to stay healthy. But Watson explains that the BRCA mutations do change your situation. Some women will have preventative mastectomies or hysterectomies to confront an extremely high likelihood of cancer.

There’s no one right or wrong answer to the question of whether you should get the test or whether you should talk to a counselor. But it can’t hurt to talk to a medical professional.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that companies who profit from selling you a genetic test are the ones encouraging you to take said test. It used to be that DNA testing companies got their business through doctors and genetic counselors. Now those companies are coming directly to consumers, and we shouldn’t assume they have our best interests at heart.

23andMe receives a steady stream of income from selling customers’ genetic information. Some of it goes to research institutions, but they also sell to for-profit companies who use that data to try to develop new drugs. Though they may have nothing but good intentions, 23andMe only profits if people take their tests. It’s not in their interest to tell you that this may not be the right choice for you.

That being said, 23andMe is also a fairly cheap and easy way of looking at genetic markers for health risks. It’s probably not the ideal way to learn about those risks—that’s why we have counselors—but it’s not the worst. And if you’re unaware of your family history—if you’re adopted or estranged from your biological family—getting a test like 23andMe can be an accessible way to learn some basics.

What happens if my test says I’m positive?

Should your test say you have a BRCA1/2 mutation, now you should definitely talk to a genetic counselor. 23andMe doesn’t directly provide those services, so your best bet is to use the NSGC’s “Find a Counselor” tool. You’ll also probably want to talk to your primary care doctor about the results, since they should be aware of your situation. It’s possible they’ll ask you to consider some proactive treatments, depending on how high your risk is. And if you test positive for one of the common BRCA mutations, they’ll definitely want to put you on a more intense cancer screening regimen than the general population.

You may think that if you know what the results mean and don’t care to do anything about them, you don’t need to see a counselor. But here’s the thing: you don’t know what you don’t know. Genetic counselors are trained to talk to people who have just received what is, undeniably, life-changing news. They will know what you need to be aware of, and should you experience any anxiety or depression from the news, they’ll get you help. And perhaps even more importantly, they’ll know if you should follow your 23andMe results with a more in-depth genetic screening. There are many other mutations out there related to breast cancer, and some of them can raise your risk for other kinds of cancer, too.

23andMe repeatedly brings up the study they did showing that receiving a positive BRCA test didn’t have negative impacts on their customers. That may very well be true, but you should also know the conclusion came from interviewing just 32 people who responded to a request to participate in the study, out of 136 people who tested positive. Out of those, 16 were men. Male carriers still have a significantly elevated risk, but their lifetime risks of 1.2 and 6.8 percent for BRCA 1 and 2 respectively are still lower than the average woman’s breast cancer risk. It also slightly elevates the risk of prostate cancer.

When asked about their emotional response to the news, three women and one man reported that they were moderately upset, indicating they “couldn’t stop thinking about the result.” Another three women and 6 men were somewhat upset, meaning they felt “initial disappointment” or “felt anxious at first but then anxiety went away.” Nine women and eight men were neutral (some of these may have been people who already knew they were carriers, since five women reported they had already been tested).

None of this meant is to scare you away from getting the BRCA test if you want it. Plenty of people find out they’re carriers and continue to live perfectly happy lives. But some people don’t. This is just to prepare you for the idea that you could get a result that genuinely changes your outlook. It may help you better prepare for a day when you do get breast cancer, or it could give you anxiety about that possibility—or both. But you won’t know until you get the results. Just because you can now do it with a few clicks doesn’t mean it’s a test to be taken lightly.

And what if it’s negative?

Since the test only looks for three mutations, a negative result on the 23andMe test isn’t a guarantee of anything. If you have a family history of breast cancer, you should go to a genetic counselor and ask about getting a full screening. It’s only with a broader test that you’ll know whether you’re truly a carrier, which can inform your future plans for cancer screenings like colonoscopies and mammograms. So unless you also want to take 23andMe for other reasons, it doesn’t make much sense to use it for BRCA. Just skip right to talking to your doctor. 23andMe may be cheaper if you’re trying to get tested without insurance, but it’s still not going to do you much good when you’re left with incomplete results.

What if I don’t want to know?

Our healthcare system is trending toward more knowledge. In general, that’s great. Patients deserve to know all the information they want about their own health. And it’s absolutely true that having a full genetic panel can give you the sort of advance warning that might save your life.

But it’s also okay to want a bit of ignorance. Some people would rather not know. You can’t unring the bell that tells you you’re very likely to get cancer, and it’s understandable if you’d like to put off the looming specter for as long as possible. Of course you should do your best to follow medical advice based on your family history. But if you already know you need to be vigilant about mammograms and other tests, it’s okay to decide that’s enough. And if your family and personal medical history gives you no reason to think you’re at an elevated risk for breast cancer, there are many experts who would tell you that the slight chance of finding a dangerous mutation isn’t worth the risk of a false positive.

No genetic test is to be taken lightly, so everyone should consider the possible outcomes before they get one. Maybe it’s right for you, maybe it isn’t. Just think about it first. And if you’re at all willing or able to do so, talk to a doctor or genetic counselor, too.