Claire Marie Porter is a Pennsylvania-based health and science journalist whose work has been published in Scientific American, The Washington Post, NextCity, WIRED, and Elle, among other publications. Find her on Twitter @_okclaire. This story originally featured on Undark.

In 2018, Kristen Miller, a high school social studies teacher from Cleveland, had an uneventful pregnancy for the first two trimesters—“textbook perfect,” she said. But then at her 32-week prenatal visit, she was told she had excess amniotic fluid, a condition that can slightly increase the risk of complications.

The following morning she went to work but noticed the fetus wasn’t moving much. Feeling something was wrong, she eventually went to the hospital. The attending physician couldn’t find a heartbeat. Miller was told her daughter, whom Miller had named Leighton, would be stillborn.

After the delivery, the doctors discovered that Leighton had suffered from two knots in her umbilical cord. The team told Miller the knots were the cause of the stillbirth—the term used to define a fetus that dies in the womb at or after 20 weeks—and that it was unavoidable. “Everyone said, ‘this is it, look no further,’” says Miller. “But I became obsessed with finding out the why.”

Roughly half of the 26,000 stillbirths per year in the US have an unknown cause, according to the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network, an organization funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Umbilical cord abnormalities—of which there are roughly seven categories, ranging from cord cysts to entanglements to knots—may account for anywhere from 10 percent to more than 25 percent of stillbirths, according to studies in the medical literature. But which types of cord abnormalities can be directly associated with stillbirth, and whether or not those abnormalities can be detected and the stillbirths prevented, is an ongoing matter of contention among medical experts. Without a stronger consensus, the standard of care—how a patient should be treated in accordance with professional guidelines—for people like Miller is unlikely to change.

Miller’s search for answers led her to a support group, where one researcher’s name came up a lot: Jason Collins, a now-retired obstetrician-gynecologist and independent medical researcher. Collins, who practiced for three decades in Louisiana, attests that these kinds of accidents are responsible for a greater number of stillbirths than the literature suggests, and that many can be prevented through extra screening that isn’t included in the current standard of care. “This issue is really not discussed,” says Collins. “There’s no awareness. It’s falling through the cracks.” Some researchers and medical practitioners agree and say the medical community should offer broader education on the topic. But far more aren’t so sure, pointing to the lack of substantial and uniform studies and cautioning against the over-screening of pregnant people.

Determining the relationship between umbilical cord abnormalities and stillbirth is difficult, says Christopher Zahn, vice president of practice activities at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), as many are common in live births as well. “It’s not an all-or-none situation,” he adds, “so establishing a true cause and effect is a challenge that we don’t have the evidence for.”

The umbilical cord is the fetus’ lifeline—it’s a source of oxygen and nutrients, and it eliminates waste. All pregnant animals that give birth to live young have one; the oldest known example is a 380 million-year-old primitive fish fossil with a mineralized umbilical cord discovered by Australian researchers in 2008. In many cultures the cord is seen as a good luck charm and is sometimes eaten as a cure for infertility. A failure of the umbilical cord means a failure of life.

Despite how vital the umbilical cord is for proper fetal development, many of its complexities remain understudied. This is especially true for its pathologies. “There is no question that cord accidents have not gotten the attention they deserve as a potential contributor to poor pregnancy outcomes,” says Alfred Abuhamad, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Eastern Virginia Medical School. Twenty years ago, Abuhamad says he cared for a patient who came to him after a stillbirth linked to a knot in the umbilical cord. He was then able to diagnose the same type of knot in the patient’s second and third pregnancies using an ultrasound and delivered the babies early to avoid complications. It was a rare occurrence, he says, that emphasizes the many unknowns surrounding the risks of umbilical cord abnormalities.

According to Abuhamad, cord accidents are likely overlooked because they exist on a spectrum, making them difficult to diagnose prenatally. Even when a diagnosis is made, there are no standardized guidelines for treatment, he said, because the relevant research and education are lacking.

The largest and most comprehensive study of stillbirths to date was published in 2011 by the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network, according to Uma Reddy, a professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Yale University. The study enrolled 663 women with stillbirths and 1,932 women with live births, and ultimately reported that umbilical cord abnormalities accounted for 10 percent of the stillbirths. That’s as far as the organization could go, stating: “As a potentially preventable cause of stillbirth, cord abnormalities deserve further investigation.”

In 2020, Reddy and colleagues from the University of Utah reexamined the data from the 2011 study and found that half of the stillbirths associated with umbilical cord abnormalities were due to compromise of blood flow through the cord. “So there is interest in understanding this,” she said. “It is a potential risk factor of stillbirth.”

Compounding the issue is the fact that researchers can’t even agree on how to define umbilical cord abnormalities. The 2020 edition of the Oxford Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, considered a leading comprehensive resource for physicians, has less than one page on umbilical cord accidents, and mentions only two possible abnormalities: cases where the cord inserts in the wrong spot, and cords with two umbilical vessels instead of the normal three.

But according to a 2019 study in the journal Medical Science Monitor, umbilical cord defects can be divided into several categories and subcategories. In addition to abnormal insertions and the wrong number of vessels, the study lists abnormal cord length, cysts, and blood clots along the cord. Among the most serious abnormalities, according to the study, are cord knots. In many cases, loose knots, also called false knots, are normal and pose no cause for concern. But diagnosis of a true knot—the cause of Miller’s stillbirth—occurs in up to roughly 2 percent of births and puts the fetus at risk of stillbirth.

The most contentious category in the Medical Science Monitor study is when the cord encircles the fetus’ body. Sometimes the cord wraps around a limb, but it more commonly winds around the neck, called a nuchal cord. Nuchal cords affect up to 37 percent of births. In most cases, a cord looping around the neck or other part of the body is no cause for concern, which is why it’s often excluded from stillbirth studies as the sole cause of a death. But according to the Medical Science Monitor study, multiple loops can pose serious complications, including stillbirth.

Although the evidence is limited, Collins believes all of these abnormalities, plus several more variations within the categories, can cause stillbirth if undetected. That the medical community can’t even agree on which cord defects contribute to stillbirth, Collins said, is due to an “educational void” in obstetric medicine.

Despite the lack of consensus, Collins said the answer to preventing stillbirths related to umbilical cord accidents is simply to perform more screening. In 2012, he laid out his recommended protocol in an article published in the journal BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth.

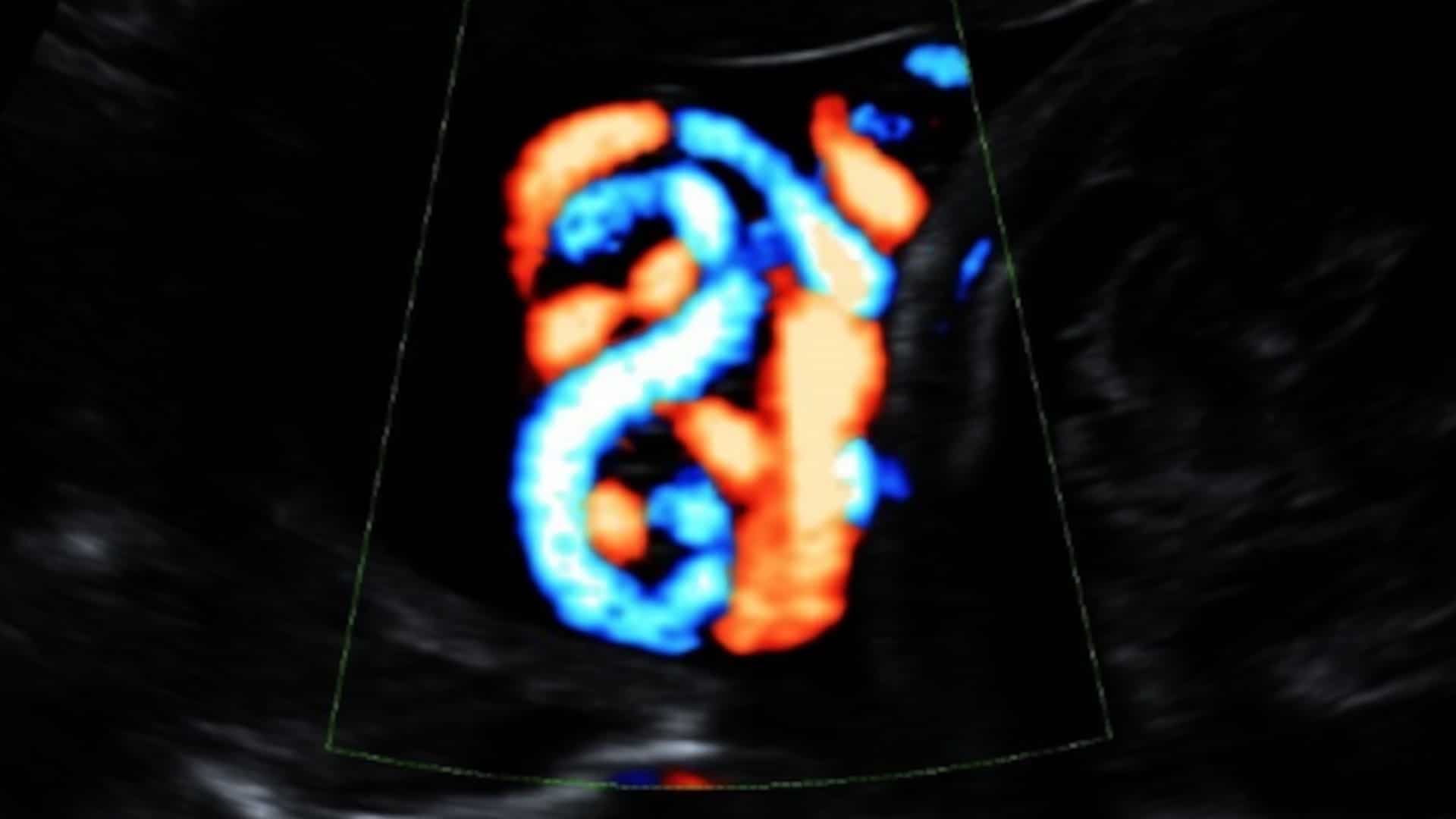

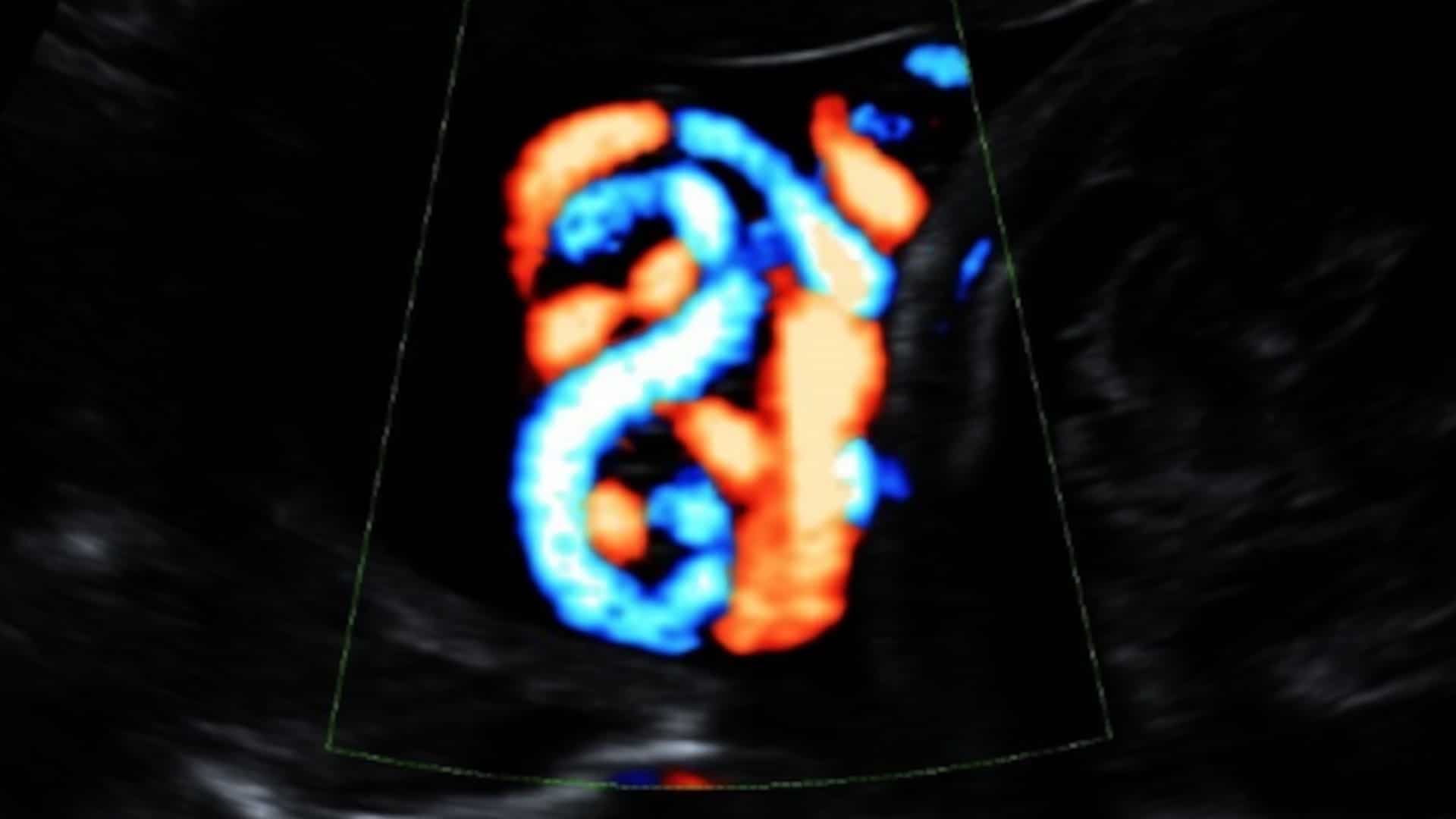

Routine prenatal care already typically involves one or two ultrasounds using a two-dimensional Doppler—which shows a flat, two-dimensional image on a screen— to check on fetal growth and health between weeks 18 and 22 of pregnancy. During these screens, most technicians do examine the umbilical cord, although they only look for blood flow and the proper number of cord vessels. Collins’ protocol calls for additional imaging with a 3D or 4D Doppler, which allows a physician to evaluate the nooks and crannies of the fetus and the cord.

Collins also advocates for the expanded use of at-home heartbeat monitoring to detect fetal stress. People who are pregnant typically go to a doctor’s office or hospital for fetal heartbeat monitoring during the day if their pregnancy is at-risk—this is the same test that Miller’s doctors used to confirm her stillbirth. The more optimal time to do it, Collins contends, would be at night when the parent’s blood pressure is lower and the foremost sign of fetal distress—brief drops in the fetal heart rate—are more likely to occur.

Collins’ protocol suggests that if the additional screening indicates an umbilical cord issue, the pregnant parent should be hospitalized and the baby monitored for 24 hours. If the fetal behavior or heart rate is abnormal, that observation time should be extended, according to the protocol, and if there are still indications of fetal distress, the medical team should consider an early delivery—whether by Caesarean section or induction.

Additional imaging with a 3D or 4D Doppler would allow a physician to evaluate the nooks and crannies of the fetus and the cord.

According to Collins, many pregnant people tell him that they don’t feel like they are getting the medical attention they need after a stillbirth. For instance, when Miller became pregnant again in 2019 with Lincoln, her “rainbow baby,”—what parents often call a pregnancy after a loss—she sought help from Collins in her third trimester. But she says that her doctors seemed offended that she’d done her own research.

“They treated me like I was being hysterical,” she says, and ordered her to stay off of Google and to stop talking to Collins. When she presented the team with her research and communications with Collins, and requested additional cord screenings, she says they would tell her that it just wasn’t the standard practice of care. “Which made me feel bad because after losing Leighton, I didn’t want the standard practice of care,” she says. “I wanted the absolute best of the best to bring Lincoln home.”

Although Collins is recently retired, he responds to daily emails and phone calls from worried parents, and coaches them in how to approach their doctors with their research. Like Miller, a lot of these parents tell him that they are made to feel unhinged by their medical teams, he adds, or that they are acting out of grief, for demanding care that is considered outside the standard.

The standard of care is a legal term, not a medical one. Jill Wieber Lens, a law professor at the University of Arkansas who specializes in stillbirth and medical malpractice, explains that the standard of care is tricky, because in many cases, especially those involving stillbirth prevention, the best option for the patient may not always be clear. In some cases, for instance, a doctor may follow the basic standard of care; in others, they may choose to include some additional screenings or other care. If doctors comply with the standard of care, they don’t “need to worry about malpractice too much,” she says. But if doctors do something “inconsistent with the standard of care and something bad happens, that’s dangerous malpractice-wise.”

Unless professional organizations recommend Collins’ protocol, it’s not going to be considered part of the standard of care. Typically, if ACOG doesn’t say to do it, most doctors will refuse to implement a new or experimental test, according to Lens. In a case of medical malpractice, she adds, juries don’t have a lot of wiggle room. With some exceptions, they have to consider whether the doctor followed the professional standard of care.

Changing the standard of care would require support from the obstetrics community more broadly. “It would mean changing entire protocols, and admitting we can do a better job,” says Karen Finkelstein, an ACOG member and leader of the medical team at Southwest Women’s Oncology in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where she specializes in gynecologic cancers.

Finkelstein lost her son to an umbilical cord accident at 32 weeks, on the same day she received a reassuring non-stress test at her obstetrician’s office. He was born with two nuchal cords and his head was buried deep in her pelvis, pulling tightly on the cords. Since her stillbirth, she has delved deep into the world of fetal monitoring and pregnancy, and said she feels very “underwhelmed” with the current guidelines.

For her two subsequent—and successful—pregnancies, Finkelstein followed Collins’ protocol. “We can change the outcome of the majority of stillbirths, and it isn’t high cost,” she says. “But we’re not doing it. It makes no sense to me.”

In 2020, Finkelstein wrote a letter to ACOG expressing her disappointment in the lack of attention to umbilical cord abnormalities in their most recent bulletin on stillbirth management, noting that the article excludes nuchal cords as a contributor to stillbirth. In her letter, Finkelstein implored the organization for an increase in screening and access to at-home fetal monitoring. She describes the response from ACOG as “passive.”

Updating a standard of care at the ACOG level requires substantial research in order to determine and understand potential links between cord accidents and stillbirth, says Radek Bukowski, a professor and associate chair of discovery and investigation in the department of women’s health at Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin. “The change in the standard of care has to be very well substantiated,” he says. For the research to be done there has to be interest, funding, and participation. All are currently insufficient, according to Bukowski, who says there is not even enough research to even conclude how frequently any umbilical cord accidents—let alone the more controversial ones—contribute to stillbirth.

Until there is enough evidence to establish a direct relationship between cord accidents and stillbirth and determine the strength of that relationship, he adds, talking about the next steps—detection and prevention—is fruitless and could be dangerous, as it may spur unnecessary medical interventions.

Collins maintains that enough research exists, in both humans and other mammals, to support routine screening for umbilical cord abnormalities. He points to a 2015 study published in the journal of the German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics that shows the ability to detect cord abnormalities prenatally with a Doppler, which he said could prevent about half of all stillbirths attributed to umbilical cord abnormalities—thousands of stillbirths worldwide.

For other experts, though, the issue remains murky. “There is evidence to support the association between Collins’ findings and poor pregnancy outcomes,” says Abuhamad, who also acknowledges Collins’ dedication to this research. “He’s contributing to the debate, which will be ongoing.”

ACOG maintains that additional screening for umbilical cord problems might not help. Screening is a population-based tool, not an individual one, says Zahn. This means the reduction of adverse outcomes has to outweigh the potential harms. While the field needs more information, “it’s important to recognize that there is ongoing research in these areas,” he adds. “If we can reduce the risk, we will.”

There are downsides to increasing fetal screening. Extra tests can make pregnant people anxious, for instance, and misdiagnoses can lead to unnecessary labor inductions and C-sections, said Cathrine Ebbing, an obstetrician at Haukeland University Hospital and an assistant professor at the University of Bergen in Norway. Many of those inductions and C-sections would be premature births. Premature infants—defined as those born before 37 weeks of pregnancy—often face serious risks to survival, as well as challenges with feeding and breathing. These babies are also at a greater risk of developmental delays, cerebral palsy, and hearing and vision loss than full-term infants, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. So increased fetal screening may “do more harm than good,” Ebbing wrote in an email. “Finding the balance is very difficult.”

Education about umbilical cord issues was limited, but that this is now changing.

Ebbing’s interest in umbilical cord problems began as a young obstetrician, when one of her patients lost her child during delivery because of a cord abnormality even though it had been diagnosed before birth. The experience, Ebbing says, marked her for life. She is now conducting ongoing research to determine the viability of routine screening for certain cord issues using ultrasound.

In the beginning of her career, Ebbing says education about umbilical cord issues was limited, but that this is now changing. “When I was a trainee I was told that a cord knot could not be the cause of death,” Ebbing wrote. “Now, I and many with me think it obviously represents a cause of death in some cases.”

In a 2018 study of certain cord abnormalities, Ebbing and her colleagues found that having them in one pregnancy more than doubled the risk of recurrence in a subsequent one. Routine cord screening, she says, is fast, relatively easy, and could be done in all pregnancies or only in those at higher risk. There are ongoing studies in Norway evaluating the feasibility of this, but it is not currently standard practice. Whether the findings will translate to other countries is uncertain, though. Health care is universal and free of cost to the public in Norway, and cost effectiveness is a major factor in increased screening and education. Norway’s population is also highly homogenous, which makes the data difficult to compare to the US.

And not all screens are created equal. Ultrasounds—whether the more common 2D version or the 3D and 4D models that Collins recommends—are “the most operator-dependent of all scans,” says Eran Bornstein, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. “It’s only as good as the person using the machine.”

The minimum expectation of cord screening on a typical ultrasound is to look at the vessels, cord insertion, and blood flow. Bornstein’s unit uses a tool called a color Doppler to see if the cord is anywhere near the cervix, which could indicate a cord insertion anomaly or a risk of cord prolapse, where the cord precedes the baby into the cervix, and which can lead to compression of the cord during labor. But that’s not necessarily standard protocol, he says, and could cause “more anxiety than value” if the wrong person is doing it.

“A closer look could be great,” says Bornstein, referring to increased cord screening. “If it’s in the right hands.”

When Kristen Miller became pregnant again in 2019, she sought care from a different medical team within the same clinic.

Lincoln was hiccupping a lot in the third trimester. Daily hiccups occurring after 28 weeks and greater than four times a day necessitate fetal evaluation, Collins had told her, as fetal jerking movements and pervasive fetal hiccups may also be related to fetal blood flow disturbances, especially cord compression. (This recommendation is based on animal studies; for ethical reasons there has not been a study in humans.)

“I brought it to the care team’s attention every week,” she says. They didn’t know it was a problem, she says, but armed with Collins’ research and guidance, she explained that it could indicate a cord issue. The baby was also hyperactive. “He was going bonkers, and it scared me,” she says.

In March of last year, following Collins’ recommendation of weekly non-stress tests and ultrasounds, Lincoln was born by early induction at 37 weeks. Her obstetrician had proposed the plan early on in Miller’s pregnancy because she thought it would give her the best chance of preventing a cord-related stillbirth, while avoiding the health risks of a premature birth.

Miller pointed out that there is no word in the English language to describe a mother who has had a stillbirth or lost a child, though there is a noun to describe others who have had a loss—someone who’s divorced, or widowed, or orphaned. She chooses to refer to herself as a “loss mom.”

She thinks this linguistic hole correlates to a lack of awareness. Which is why she’s found herself advocating for “loss moms” and in the summer of 2019 joined the nation’s leading stillbirth advocacy group, the Star Legacy Foundation, as secretary. She stresses the importance of Collins’ research and puts other loss moms in touch with him if they have a history of umbilical cord issues. “You can carry it silently and alone,” she says, “or you can get out there.”