We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

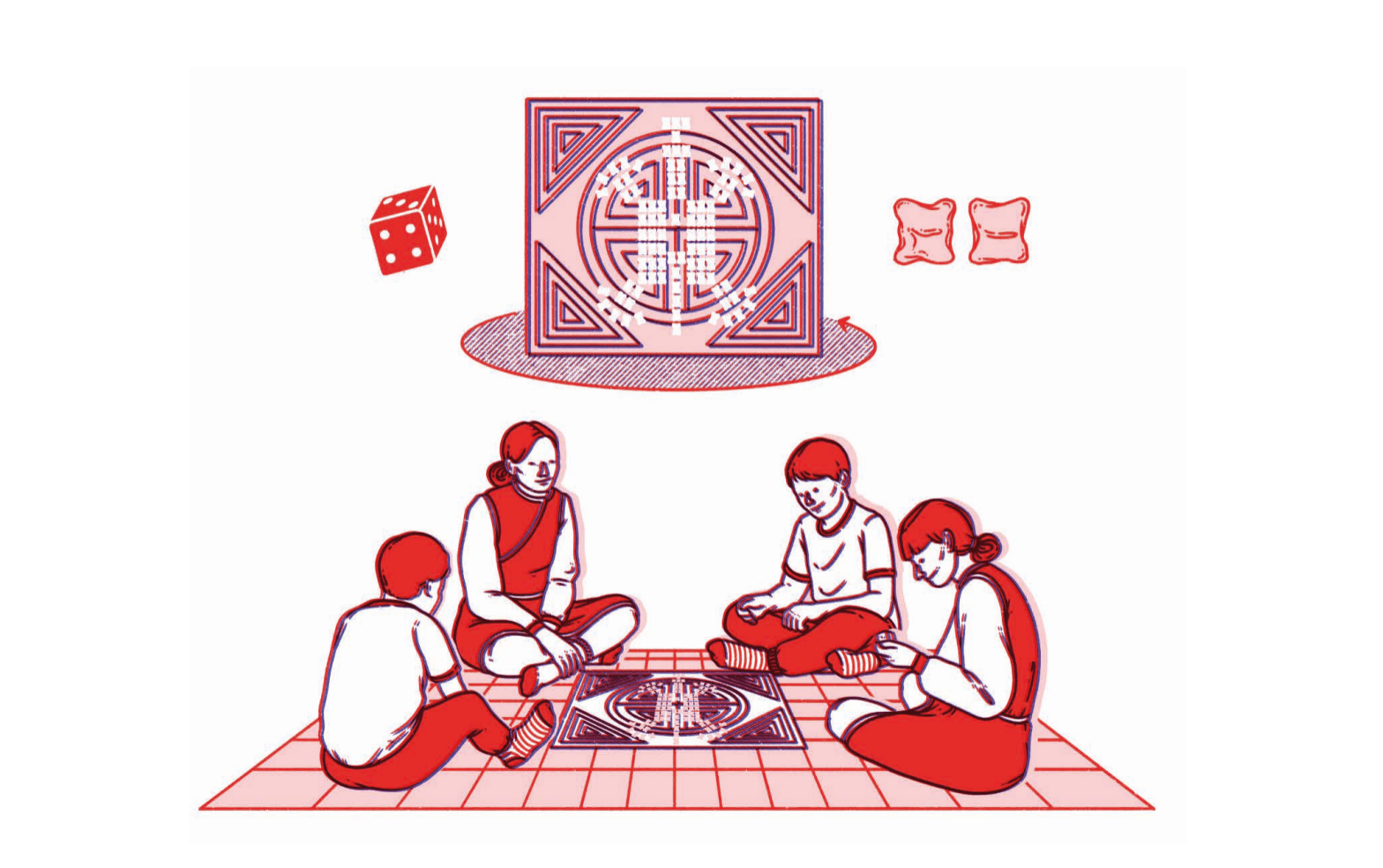

You don’t need to look good to play Алаг мэлхий өрөх, a traditional Mongolian game that translates to “Multicolored Turtle,” but the elders kneeling around the board on cushy rugs all dress to impress. The women wear dangling earrings, rings on each hand, and deels, colorful loose-fitting tunics tied at the waist with silken sashes and ornate buckles.

Resplendent in a red deel with gold spots and a black fur cap, Ts. Maanigumben, a schoolteacher and the oldest of the four players, covers the playing area with a layer of shagai, sheep knucklebones polished and dyed in a variety of vibrant colors.

Mainstream Western games have nothing like Multicolored Turtle, which combines strategic play with ceremonial and storytelling components. But for Indigenous Mongolians, the game is both familiar, and a buttress to their traditional nomadic culture. The turtle is built from 108 shagai, a sacred number in Buddhism, while the colors represent the gemstones and elements that define the cosmos in Mongolian riddles and legend.

Traditional ger homes have red-trimmed bags of shagai hanging from the wall, for use in up to 200 different shagai games. Mongolians shoot shagai with guns or traditional throwing weapons, slide shagai across frozen lakes at targets, read fortunes in the arrangement of cast shagai, toss and grab shagai like jacks, and flick shagai off small launching boards to knock down stacks of yet more shagai. When couples marry, their home is inundated with gifts of shagai; sometimes, the bones are even buried with the dead.

But after centuries of bringing Mongolians together, shagai games like Multicolored Turtle are beginning to fade away. As young people migrate into city areas and turn to Western-based video games, many are forgetting the rules altogether. “Modern families are becoming reluctant to collect anklebones … [T]here is an absence of shagai games during family time,” according to a United Nations program which found that, in each of Mongolia’s 21 governmental aimags, elders were concerned about the decline.

The waning of Multicolored Turtle in Mongolia is just the tip of a globe-spanning problem. In Kenya, in Brazil, in Greece, in Inuit lands, everywhere, traditional games of Indigenous peoples are going dark. With each extinction, a bit of culture is lost. “The public at large has very little, if any, knowledge of the scope and wealth of cultural heritage in terms of traditional games and sports,” a UN report found, though there’s no formal estimate of how many activities might be imperiled.

[Related: Local languages are dying out and taking invaluable knowledge with them]

With some games already lost, in 2007, the UN formally recognized the right of Indigenous people “to maintain, control, protect and develop” traditional games as part of a broader declaration on human rights. That cleared the way for a UN-sponsored initiative that aims to document, digitize, and distribute hundreds of competitive pastimes in the Open Digital Library on Traditional Games, or ODLTG. The sheer scope of the project is difficult to absorb.

Organizers will catalogue every game that exists, and every game that ever existed—and that’s just to start. As they staunch the bleeding of knowledge by creating a global gaming crypt, they will then use technology to build a Noah’s Ark that carries cultural games into a future where they can be played by millions of youngsters with cell phones, Xboxes, and other devices. From there, inventors and designers can adapt them further to match cross-cultural tastes and modern trends.

Ironically, the very technology that has displaced traditional games for children around the globe may be the best hope for making those games relevant to future generations. For years, while quietly hoovering up data sheets on games like Multicolored Turtle, ODLTG has also been developing and harnessing the latest video gaming software and hardware.

Games constantly wink in and out of existence, but the overall trend is one of loss.

Some are already extinct—though tantalizing clues survive. Anthropologists are still stymied by the rules of Senet (or “zn.t n.t ḥˁb”), a grid-based board game that hieroglyphs show was played by ancient Egyptians for 2,000 years. Others, like capoeira (a blend of dance, music and martial arts that originated among Angolan slaves in Brazil in the 1500s), are becoming rarefied as more folks spend time playing monolithic digital blockbusters like Fortnite and Free Fire.

With every passing day putting more at risk, in 2015 the ODLTG began deploying more than 100 people to meet with local cultural experts and comb the streets of a handful of pilot countries. The team captured video, pictures, and text descriptions of 68 games in Brazil, Mongolia, Bangladesh, Greece, Kenya—with more on the way from Morocco, Mexico, and Kazakhstan.

By bringing those ethnographers together with software developers, the ODLTG is creating a space where what they’ve documented can blend into nuanced digital worlds and be accessed through virtual- and augmented-reality interfaces. The corporate partners funding the ODLTG—initially Tencent, a massive Chinese videogame company and currently Venture Gaming, a Tencent affiliate with offices in China and the US—give the project’s diverse gaming DNA access to emerging technologies. Tencent is investing in somatosensory games (they read player gestures to drive the on-screen action, a la Nintendo Wii), on-demand cloud-based streaming games, (which allow play without downloading or purchasing particular gaming devices, a la services like Steam), higher graphic resolution, and sophisticated artificial intelligence systems.

For example, at the Communication University of China, a student-driven ODLTG project allows users to slip on a pair of goggles to enter a meticulous digital recreation of the Qing Dynasty, circa 1644. Here, calligraphy adorns wooden walls above an ornate hand-carved writing desk, and players engage in a rousing traditional game of tou-hu, or “pot casting,” by reciting poetry and throwing arrows into ornate long-necked clay pots.

Traditional game elements are also making their way into existing Tencent properties, like the coveted cultural outfits in the mobile app Love Nikki-Dress Up Game!, and the capoeira challenges in QQX5, a dancing game popular in China.

“Most games have the biases of the colonizers. They almost never take the view of the colonized.”

Rik Eberhardt, program manager of the MIT GAME LAB

Though the project was motivated by a desire to protect traditional games, the biggest beneficiary may be the West’s mainstream gaming community, says Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Rik Eberhardt, who was tapped by UNESCO to give input for the ODLTG.

Eberhardt works as program manager of the MIT Game Lab. He spends part of each work day sitting in his tiny office, hemmed in by the hundreds of board games lining the walls and stacked floor to ceiling.

Far too many of the games piled in his office, he says, feature actions that unconsciously or deliberately reflect a set of four colonial values: exploration, expansion, extermination, and extraction. “Most games,” Eberhardt says, “have the biases of the colonizers. They almost never take the view of the colonized.” Popular games from Stratego to Risk to Monopoly suffer from the fact that they’re all trapped in a paradigm built on fallen global empires, an artificial blinder that obscures the boundless possibilities.

“If you think about Indigenous viewpoints, it’s hard to do if you don’t have them in the room when you’re designing. But the relationships between objects, the relationships between rules, the reasons for rules can be very different,” Eberhardt says.

The ODLTG will help Indigenous values bleed into the Western gaming zeitgeist. This will be made possible by a public-domain database that encourages direct participation from the broadest array of gamers imaginable—elder Mongolians kneeling in a ger, an Ivy League academic game researcher, a Kenyan pre-teen who only has a cast-off Apple phone, Californian high schoolers tinkering with the back end of the latest gaming system.

If they succeed, a user in, say, the Inuit Nunatsiavut community near the Arctic Circle will be able to upload information on a traditional Inuit ear-pulling contest, a pain-inducing tug-of-war in which competitors are tied to each other, ear-to-ear until one submits. Then, another user in, say, Nuremberg can download the information to organize an ear-pulling contest—or create a new, hybrid version that can be uploaded for still more users around the globe to play or tinker with.

“It’s about not letting go of anything,” Eberhardt says. “Acknowledging the old, and the traditional, and acknowledging the new. It’s all valuable.”

But to really achieve that sense of fun, vibrancy, and endless variety, they need to successfully tap the creative potential of the world’s 1.2 billion young people.

Though it is still in a pilot phase, the ODLTG glitters with promise, especially for budding developers who are helping UNESCO and Tencent prototype the first games. In 2017, Chris Preller and Rachel Siegel, students at the NuVu School for Innovation in Cambridge, Massachusetts, waltzed between the outsized video monitor and their computer coding stations, shoulders bobbing to the rhythm of Kanye’s “Life of Pablo”—mouths full of microwaveable mac and cheese.

Preller and Siegel had been studying videos of capoeira. Bare-chested men did handsprings, somersaults and spun like dervishes, throwing precise volleys of roundhouse kicks designed to pass harmlessly within an inch of their partners, while appreciative onlookers chanted and played a percussive beat on Brazilian berimbaus.

Preller wanted to port capoeira’s unique feel into digital competitions against remote opponents in Korea or Iceland. She pictured onscreen avatars mimicking her body movements in real-time, with an automated scoring system and a user-group that could watch the livestream and create a community of friendly onlookers.

To capture body movements, the high schoolers hacked an X-box Kinect, which uses a 30 frame-per-second camera to detect and render shapes from its surroundings. It judges depth by shooting a near-infrared beam of light and measuring the reflected light, resulting in a flood of 9 million pieces of data per second.

Using an API and computer models to smooth out the images, they ran that data stream into a visual design software called Processing, creating avatars that would dance and kick along with the players.

The first effort failed. So did the second. So did the 25th.

Though their erasers were soon worn to nubs, Preller says they didn’t feel the pressure the way many adults would. “We messed around a lot and had a lot of fun with it,” she says.

They were, on some level, children at play. And that approach eventually worked, when they were able to turn around agile, real-time avatars ahead of an international ODLTG delegation, paving the way for the first-ever intercontinental capoeira game.

Their project, which is currently held by UNESCO and awaiting further development, demonstrated that two high school students could digitize the capoeira experience in a way that had appeal to American video gamers.

When the ODLTG goes public (the hoped-for 2020 launch was “stalled due to the COVID-19 pandemic,” according to Jingxiao Wang, a China-based UN coordinator), the energy of Preller and Siegel will be magnified by thousands of young people uploading their own regional games for reuse.

The ODLTG is really two unique efforts: the public-facing side hopes to mainstream a never-before-seen landscape of diverse games that pierce the colonial bubble, and the back end aims to build a platform that embodies the UNESCO ideals of human rights, cultural respect and equal access.

It’s a delicate balancing act. Because they believe the culture of the ODLTG will be driven by its underlying technology, UNESCO’s international team is neck-deep in building a platform where inclusion is not just an aspiration, but a baseline necessity.

When Isabel Bernal, a Madrid-based data-access consultant, sat down to develop guidelines, she drafted an ambitious wish list of functions and features. The roadmap for the library’s digital architecture includes Free and Open Source Software (FOSS), multilingual capabilities, ground-up inputs from the peoples of the world, and an artificial intelligence to minimize the content management labor.

“Opening up access to cultural contents is most exciting when it is repurposed,” Bernal says.

That repurposing will include videos used in classrooms; toys and artifacts serving as grist for 3-D printing companies; geographical data to allow for traditional game tourism; and hackathons where coders will challenge one another to create the best update to a traditional game.

After aborting a first attempt to publish the ODLTG on WordPress, the job of building the platform fell on the shoulders of Chris Gallant, a videogame industry veteran. Gallant’s specialty is a kind of software glue called Islandora: It takes a digital repository program, Fedora Commons, and connects it to a digital presentation program, Drupal.

If you’ve ever gone to the Baseball Hall of Fame website to admire the bat Babe Ruth used to hit 28 home runs for the Yankees in 1927, or browsed researcher notes on the lymphatic glands of whales in the Smithsonian Institution research files, then you’ve probably used Islandora, though it’s largely invisible to the end user.

[Related: How Ubisoft created the detailed world in Assasin’s Creed Valhalla]

After working on the ODLTG for about a year, Gallant says it differs from most digital repositories. First, the curation will be driven by “any old user” from the public, rather than trained academics. Gallant’s team is also fine tuning an artificial intelligence that reviews video and photos to make cross-national connections between games; if a Canadian uploads ice hockey, the system will point users toward other puck-based games, like the Latvian tabletop game of Novuss or the Indian billiards game Carrom.

Of the many struggles, one of the most stubborn is the inability of creating an AI that can identify obscenities across different regions. “Different cultures are going to have different levels of sensitivity to certain things,” says Gallant. In America, “puff” means a bit of smoke, but in Germany, it’s a brothel. “Poes,” meanwhile, signifies a cat in Holland, but is a vulgar slur in South Africa. Instead of trusting a program to navigate those intricacies, the system flags potentially bad words for later review by a network of regional experts who can judge content with knowledge of the relevant culture, and then publish it with the click of a button.

Once the ODLTG goes live, the vast majority of games will be identified and uploaded by the public, and organizers hope that the creative output of the world’s children will help them spawn a new generation of gaming that makes Fortnite look like Pong.

Though the potential upside is huge, Qingyi Zeng, a Hong Kong-based UNESCO coordinator for the project, says that once they’ve rolled out the red carpet, success will depend on whether people turn en masse to the ODLTG and make it their own. “The world,” she says, “is welcome.”