For the past 25 years, Lake Palcacocha, perched above the Peruvian city of Huaraz high in the Andes, has been filling up with water. It sits just at the foot of a glacier, and as the glacier has retreated, the lake has flooded to six times its 1995 levels. It now covers an area the size of about 200 football fields and is nearly 300 feet deep in some places.

The lake is held back by a rim of glacial debris, reinforced by manmade structures. “You’ve got a very precarious situation,” says Gerard Roe, a glaciologist at the University of Washington. “Were an avalanche or rockslide to land in this lake, it would create a tsunami-like wave that would breach the boundary, and send a torrent of water down the valley.” Within an hour, it would hit the city as a mass of debris.

The last time such a flood occurred, in 1941, 1,800 people died. A similar incident in the present-day city could kill 6,000.

Now, research published in Nature Geoscience finds that the risk to all of those lives are directly attributable to climate change. That research is the latest step in the growing field of climate change attribution science, which connects day-to-day events like heat waves, floods, and superstorms to human-caused warming.

“There are a significant number of people threatened by this potential flood,” says Rupert Stuart-Smith, one of the study authors who researches legal liability and climate attribution at the University of Oxford. “So there’s significant public interest in knowing what the role of climate change is in this setting. And we realized that we have the tools to investigate.”

The looming danger to Huaraz has long been attributed to climate change, and in 2015, a farmer and mountain guide who lives in Huaraz filed a lawsuit alleging just that. His complaint, which is working its way through the German courts, argues that the German utility RWE should pay part of the cost of strengthening the city’s flood defenses.

This research could provide a key piece of evidence in that case, by directly connecting emissions to the growth of the glacial lake.

“The fundamental principle underpinning climate change attribution science is counterfactual analysis,” Stuart-Smith says. In other words: What would have happened if humans hadn’t warmed the climate? And how does that differ from reality?

To establish that climate change had directly caused the flood risk, the researchers had to link together three points. First, they needed to show exactly how much anthropogenic warming had shifted temperatures around Lake Palcacocha. Second, they had to prove that the glacier’s retreat was in fact due to those temperature changes. Finally, the flood risk at the lake had to be directly linked to that melting ice.

That relied in part on research by Roe and his colleagues at the University of Washington, who had recently developed a method for attributing glacial melts to climate change. “Glaciers are icons in the public and scientific imagination,” Roe says. “So it was one of those things that everybody knew, but hadn’t been officially demonstrated in the literature.”

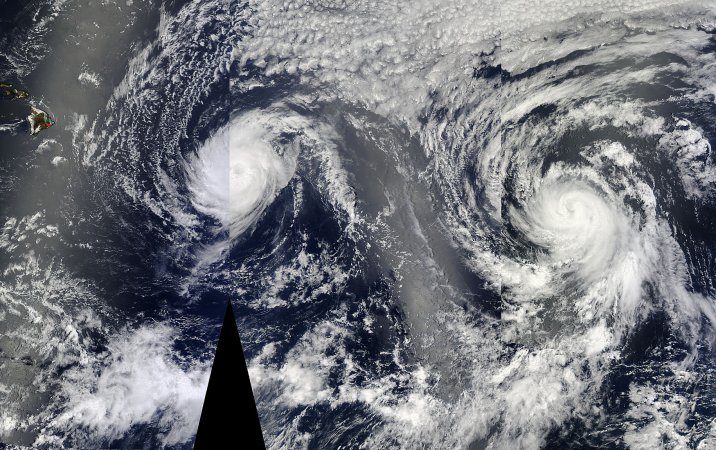

[Related: Slow, meandering hurricanes are often more dangerous—and they’re getting more common]

“What we found was that in the absence of climate change, the observed retreat of the glacier would not have been possible,” Stuart-Smith says. Therefore, climate change was directly responsible for the threat that meltwater posed to the city.

Among the most surprising results, Roe says, is that human-induced climate change not only elevated the future risk of floods from Lake Palcacocha—it was responsible for the flooding in 1941. “That’s shockingly early in most people’s view of when anthropogenic climate change became an issue.”

“Glaciers end up being purer signals of climate change than … thermometers or pressure gauges,” Roe says, and humans have been warming the planet since the 1850s. “Therefore, the signal of climate change showed up quite early relative to other things we think about more commonly, like the temperature record.”

Although the research was conducted independently, it’s likely to have important implications for the suit against RWE.

The study provides firmer ground for climate litigation, says Aisha Saad, a fellow at Harvard Law School’s Program on Corporate Governance. (She collaborates with Stuart-Smith on other projects, but was not involved in the research.) That’s in part because the findings establish evidence in a way that the legal system can interpret.

“It could be it that the scientific evidence exists to support a legal claim,” she says “But it’s not being framed in that way.”

In past civil liability cases, especially those concerning cigarettes and tobacco, courts and scientists have figured out how to develop language in common. As climate lawsuits proceed across the United States and across the world, Saad says there are glimmerings of that emerging. One district court judge, William Alsup, invited climate scientists to give him a tutorial as he prepared for two suits filed by California cities against petrochemical companies. (He ended up ruling against the cities, although the case is still in appeals.)

Stuart-Smith has been involved in other research that began establishing a direct link between climate and human health, including a December paper in Health Affairs that outlined strategies for attributing heat wave deaths and hospitalizations, among other things, to climate change. The scientific tools exist, he says, to begin connecting emissions not only to physical events, but all the way through to the illness and death that those events can cause.