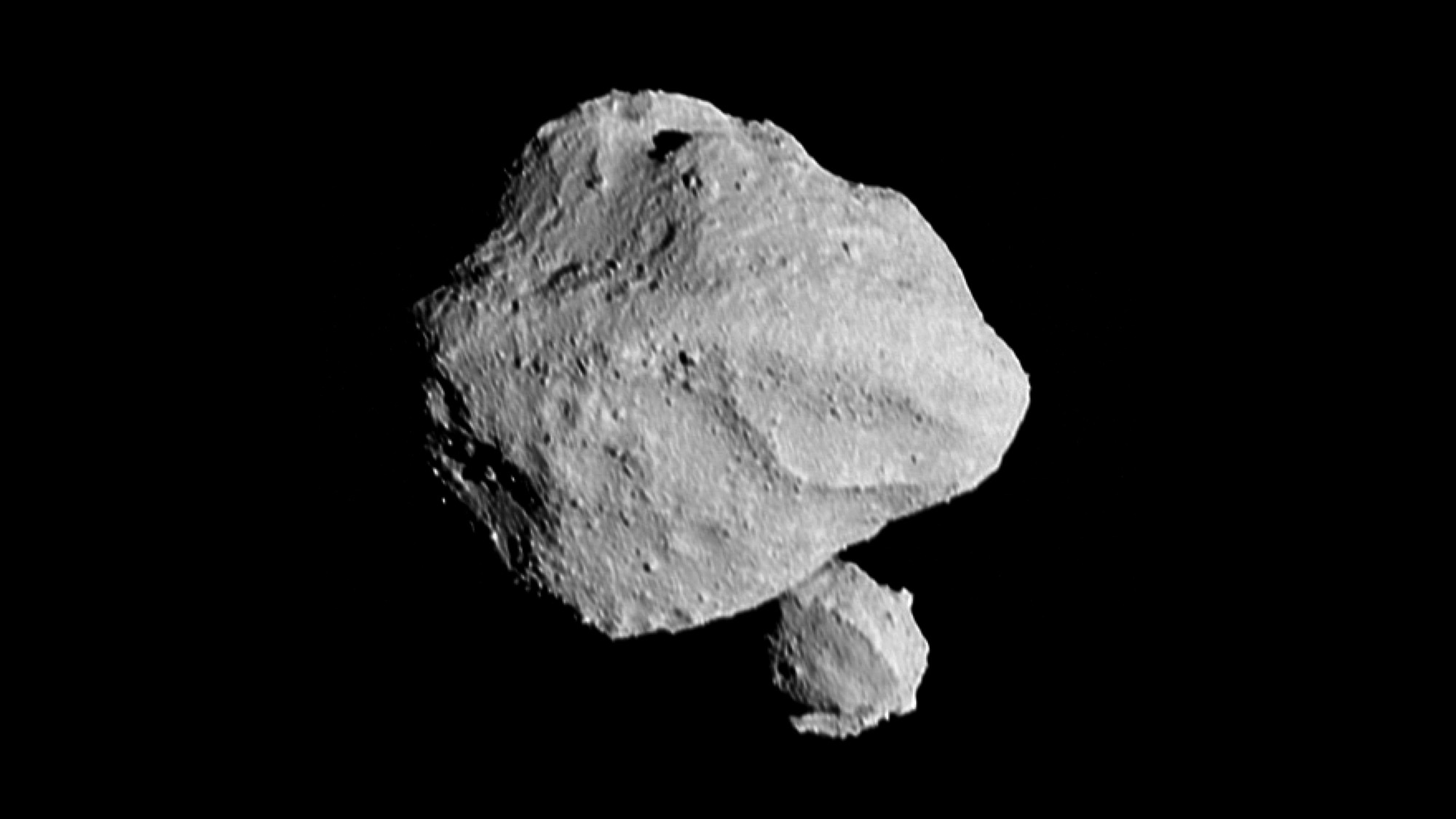

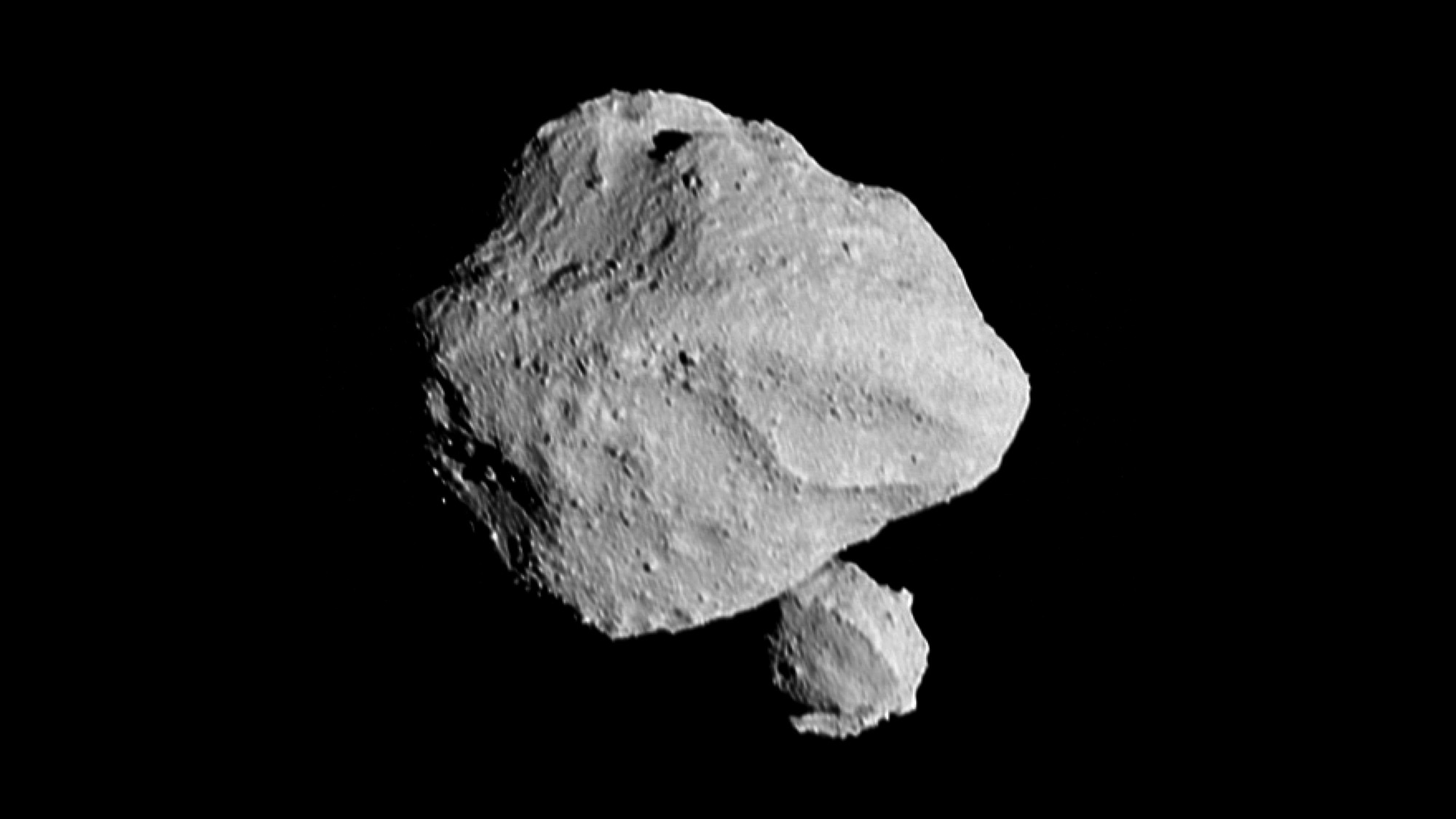

The freshly released images from NASA’s Lucy spacecraft’s first asteroid flyby reveal that Dinkinesh is actually a binary pair. A binary asteroid pair has a larger main asteroid and a smaller satellite orbiting around it. In the weeks leading up to the flyby, the Lucy team had wondered if Dinkinesh was actually a binary system because Lucy’s instruments detected the brightness of the asteroid changing over time. This is a sign that something is getting in the way of the light, likely a body orbiting the main space rock.

[Related: NASA spacecraft Lucy says hello to ‘Dinky’ asteroid on far-flying mission.]

From a preliminary analysis of the first available images, the team estimates that the larger asteroid body is roughly 0.5 miles at its widest and that the smaller body is about 0.15 miles in size.

Dinkinesh is another name for the Lucy fossil that this mission is named after. The 3.2 million-year-old skeletal remains of a human ancestor were found in Ethiopia in 1974. The name Dinkinesh means “marvelous” in the Amharic language.

“Dinkinesh really did live up to its name; this is marvelous,” Hal Levison, Lucy principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute, said in a statement. “When Lucy was originally selected for flight, we planned to fly by seven asteroids. With the addition of Dinkinesh, two Trojan moons, and now this satellite, we’ve turned it up to 11.”

The November 1 encounter primarily served as an in-flight test of the asteroid-studying spacecraft. It specifically focused on testing the system that allows it to autonomously track an asteroid as it whizzes by at 10,000 miles per hour. The team calls this its terminal tracking system.

“This is an awesome series of images. They indicate that the terminal tracking system worked as intended, even when the universe presented us with a more difficult target than we expected,” Lockheed Martin guidance and navigation engineer Tom Kennedy said in a statement. “It’s one thing to simulate, test, and practice. It’s another thing entirely to see it actually happen.”

It will take up to a week for the remainder of the data from the flyby to be downloaded to Earth. This week’s encounter was carried out as an engineering check, but the team’s scientists are hoping this data will help them glean insights into the nature of small asteroids.

“We knew this was going to be the smallest main belt asteroid ever seen up close,” NASA Lucy project scientist Keith Noll said in a statement. “The fact that it is two makes it even more exciting. In some ways these asteroids look similar to the near-Earth asteroid binary Didymos and Dimorphos that DART saw, but there are some really interesting differences that we will be investigating.”

[Related: Why scientists are studying the clouds of debris left in DART’s wake.]

The Lucy team plans to use this first flyby data to evaluate the spacecraft’s behavior and prepare for its next close-up look at an asteroid. This next encounter is scheduled for April 2025, when Lucy is expected to fly by the main belt asteroid 52246 Donaldjohanson. This asteroid is named after American paleoanthropologist Donald Johnson, one the scientists who discovered the Lucy fossils.

Launched in October 2021, NASA’s Lucy mission is the first spacecraft set to explore the Trojan asteroids. This group of primitive space rocks is orbiting our solar system’s largest planet Jupiter. They orbit in two swarms, with one moving ahead of Jupiter and the other lagging behind it.

There are about 7,000 asteroids in this belt, with the largest asteroid estimated to be about 160 miles across. The asteroids are similar to fossils and represent the leftover material that is still hanging around after the giant planets including Saturn, Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune formed.

Lucy will then travel into the leading Trojan asteroid swarm. After that, the spacecraft will fly past six Trojan asteroids, including binary asteroids like Dinkinesh: Eurybates and its satellite Queta, Polymele and its yet unnamed satellite, Leucus, and Orus.

In 2030, Lucy will return to Earth for yet another bump that will gear it up for a rendezvous with the Patroclus-Menoetius binary asteroid pair in the trailing Trojan asteroid swarm. This mission is scheduled to conclude some time in 2033.