In late November 1974, the world of archeology changed when scientists discovered Lucy (a nod to a famous Beatles track played over and over at the dig site), a 40-percent complete fossil of a young female Australopithecus afarensis in Ethiopia. This species of ancient hominid was living and walking around on two feet in East Africa 3.7 to 3 million years ago, long before the earliest stone tools were made. While Lucy and her relatives were shorter, more ape-like, and had smaller brains than Homo sapiens, they showed just how long human-like creatures were evolving and strolling about on Earth.

Just recently, scientists uncovered that Lucy, whose remains are housed in a specially constructed safe in the National Museum of Ethiopia, may have been even more like us than we thought—and considerably more muscular in the legs department. According to a new paper published on June 13 in the journal Royal Society Open Science, Lucy could walk around upright just as well as a person.

[Related: The ‘granddaddy’ of all early hominins walked on Earth a lot longer than we thought.]

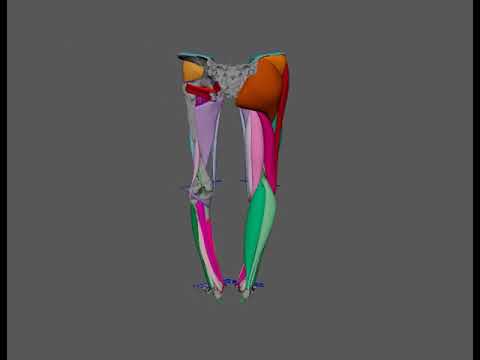

Previously, paleoanthropologists disagreed on Lucy’s bipedal stance. Some thought she likely waddled around with her back hunched over, not unlike today’s chimpanzees. However, Ashleigh Wiseman, a paleoanthropology research associate at the University of Cambridge, created 3D models of the leg and pelvis muscles of the 3.2 million-year-old Australopithecus afarensis. After recreating 36 muscles in each of the ancient hominids’ legs, she found that Lucy’s stance was quite similar to humans.

Not only could she walk like a Homo sapien, but she was considerably more muscular than us—her calves and thighs were more than twice the size of those of modern humans. Her thighs in particular were made up of 74 percent muscle, compared to the average 50 percent split between fat and muscle in our species today.

This shouldn’t be too surprising, however, given the world ancient hominids lived in. To manage life in East Africa 3 million years ago, Lucy and her cousins would’ve had to roam wooded grasslands, while swiftly switching to climbing forest canopies, Wiseman said in a statement.

“We are now the only animal that can stand upright with straight knees. Lucy’s muscles suggest that she was as proficient at bipedalism as we are, while possibly also being at home in the trees,” Wiseman added. “Lucy likely walked and moved in a way that we do not see in any living species today.”

[Related: 2.9 million-year-old tools found in Kenya stir up a ‘fascinating whodunnit’.]

3D models have previously been used to reconstruct the muscles of other lost species. In fact, Wiseman mentions that the method has helped paleontologists figure out the shockingly slow running speeds of T. rexes. But recreating the builds of our ancestors lets us see how far we’ve come—and how much muscle we’ve lost as our lifestyles have shifted.

“Of course, in the fossil record we are left looking at the bare bones,” Wiseman told CNN. “But muscles animate the body—they allow you to walk, run, jump and even dance. So, if we want to understand how our ancestors moved, we first need to reconstruct their soft tissues.”