Anthropologists are still wrestling with their obligations to the living and dead

One major journal develops a rough draft for handling human remains.

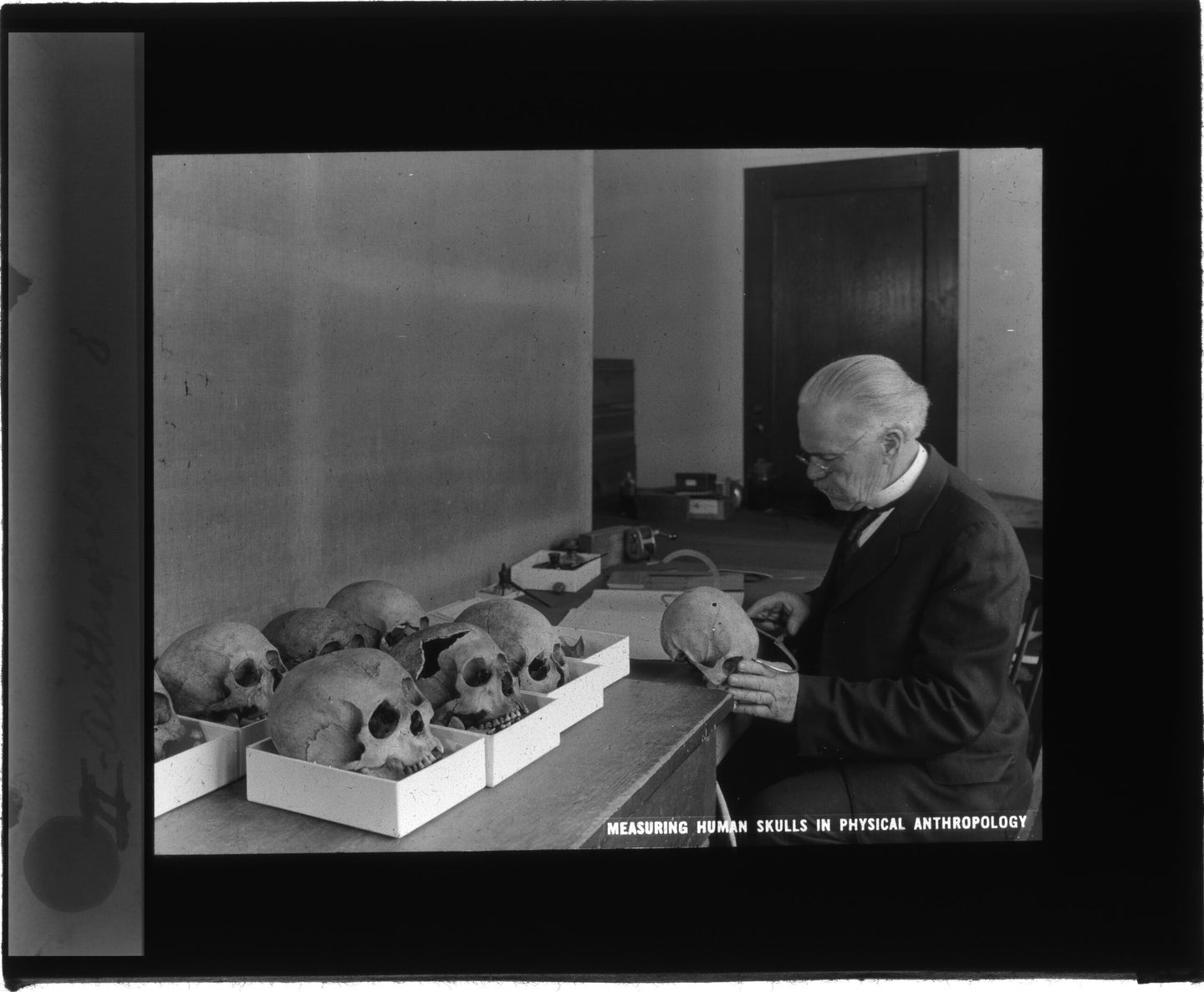

Across the United States, the remains of more than 10,000 people sit in museum and research collections. Some are as small as a fragment of bone. Others are whole bodies. For more than a century, these skeletons have been fundamental to our understanding of how society, culture, and technology have shaped human bodies—and even shaped forensics and epidemiology. Since the 1990s, the anthropological community has developed a framework for returning remains to their descendants. But it’s been slower to address an equally important question: how to conduct research on the bodies of dead humans with the consent and input of their living kin.

Now, researchers are working to formalize how anthropologists consult with descendant communities. In January, the American Journal of Biological Anthropology (AJBA) announced that any submissions to the journal would need to comply with ethical requirements for human remains used in the research.

The decision is part of an ongoing conversation within the field of bioanthropology—a discipline that uses biological tools like genetics to study human life throughout history—to redefine its responsibilities to both its subjects and their descendants. The conversation has taken on a new urgency with the emergence of advanced genetic and molecular techniques that dramatically increase the amount of information that can be learned from a body. That technology can also be uniquely invasive, requiring the destruction of bone, and producing data about living communities. The AJBA represents the perspective of a leading scientific association, the American Association of Biological Anthropologists (AABA), and is one of only a few other major journals in the field to articulate community engagement standards.

The ethics of utilizing human remains in the name of science is set against a dark history. In the 19th and 20th century, early bioanthropologists—including the AJBA’s founder Aleš Hrdlička—robbed Indigenous graves to build collections of human bones, and those collections were used to develop pseudoscientific theories about the biological nature of race. As anthropologist Chris Stantis wrote on Twitter recently, that founder wouldn’t have been able to publish much of his research under the new guidelines.

[Related: Don’t buy stolen artifacts—here’s how to ethically collect science memorabilia]

Trudy Turner, AJBA’s current editor-in-chief who studies the evolution and adaptations of primates at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, has been involved in discussions about the handling of human remains for decades, starting with questions about genetics research.

The new guidelines came about as journal reviewers asked for ethics statements on specific papers submitted to the journal. Until this year, “[the journal] had guidelines for animal studies, clinical trials,” says Turner. “we just didn’t have any set guidelines on the use of human remains.”

Plenty of bioanthropologists have worked closely with descendant communities, and have disproven biological interpretations of race. But the field’s longstanding practices on consent have been harder to shake, leading to high-profile legal battles. In the early 2000s, the Havasupai Tribe in Arizona discovered that their DNA, which they believed had been collected for diabetes research, was used in a wide range of studies on human migration. After suing the university that held the samples, the nation banned further research on their land. Between the 1990s and 2016, anthropologists fought the repatriation of a 9,000-year-old man found in southern Washington, on the basis that he was so ancient as to be culturally unconnected to specific modern Indigenous nations. Last year, Philidelphia medical examiners discovered that bones belonging to two people—believed to be two children—killed in a 1985 bombing by Philadelphia police were held for years in a University of Pennsylvania archive, and had been used in an online course without the knowledge or consent of their relatives.

“What we’re hoping is that as research is being planned, researchers take into consideration their obligations to the community.”

— Trudy Turner, editor-in-chief of the American Journal of Bioanthropology

The new journal requirements apply to research that uses data from a variety of remains, from physical bones, photographs, casts, genetic information, and isotopes extracted from skeletons. Authors submitting papers will need to provide a statement describing how they identified a descendant community, what permissions they received from that community, and a plan “for the free sharing of information with descendent groups while also guarding the privacy of sensitive information.”

The requirements still leave many of the thorniest ethical questions open. The journal doesn’t specify how authors should determine an appropriate descendant community, or what level of community consultation is appropriate. And critically, the requirements only apply to newly collected data—already published “legacy data” is exempted.

Turner stresses that the guidance is “not going to be the final word on everything.” The point of the current guidelines, she says, is to push researchers to begin studies with a different mindset.

“What we’re hoping is that as research is being planned, researchers take into consideration their obligations to the community,” says Turner—obligations like investigating questions proposed by a descendant community, and respecting when they do not want studies conducted. “You wouldn’t get to something contested, because you’ve thought about it ahead of time. That’s the goal.”

But Vanderbilt University geneticist Krystal Tsosie, who is a citizen of the Navajo Nation and ethics and policy director of the Native BioData Consortium, says she’d like to see more clarity from these guidelines to address field-wide concerns. “I see a step in a positive direction for transparency in community engagement, but we really should have more specificity on what [the guidelines] should look like,” she says. “Is this an ethical statement that will be front and center in the main manuscript, or will this be hidden in the supplemental materials?”

Participating in genetics research has not just hurt Indigenous people historically, Tsosie says—it poses ongoing risks. Badly framed research across the field has “reinforced stereotypes relating to genetic ancestry and race,” or assumed that a person’s Indigeneity could be boiled down to their genetic profile. That’s a risk for marginalized people across the world. Earlier this year, Nature documented dozens of papers on DNA from Roma people that used racist language or proposed biological racial distinctions.

[Related: Collecting missing demographic data is the first step to fighting racism in healthcare]

Turner says that AJBA will look to a newly formed AABA task force to continue revising its guidance, called the Task Force on the Ethical Study of Human Materials. The group is still in its early stages.

“What we decided early on is that if we wanted to create something that is adaptable and meaningful to our members, trying to create a roadmap on a global scale is unrealistic,” says Benjamin Auerbach, an evolutionary biologist who specializes in anatomy at the University of Tennessee and co-chair of the task force. “We decided that we would focus on engaging with the African American community in the United States.”

The goal is to develop a framework for identifying communities that have a stake in research on human remains, and creating opportunities for conversations between them and scientists.

“Hopefully we can give [other bioanthropologists] a broad set of tools so they know how to enter into these conversations, and know what they need to communicate,” says Auerbach. “I think the biggest thing they need to learn is to listen, and not just talk at communities.”

“This was a human being, who had a life, who loved, who had all the frailties of every other human being, and deserves to be respected.”

— Fatimah Jackson, co-chair of the Task Force on the Ethical Study of Human Materials

That will require a culture shift within the profession, but one that should benefit science as well as descendant communities, says Fatimah Jackson, an evolutionary biologist who studies population biology at Howard University, and the task force’s other co-chair. “The communities that we tap to do the research, they never hear back from us [scientists] once the research is done,” says Jackson. “In the absence of full disclosure and completing the circle, there’s an opportunity for lots of misunderstanding.”

Addressing that communication gap also requires scientists to provide descendant communities with education to make informed decisions about the research process, she says. Setting clearer expectations for dialogue, Jackson says, will hopefully build a “kind of camaraderie will improve the quality of science.”

Jackson previously served as curator of the W. Montague Cobb collection at Howard, an early anthropological collection of the remains of Black people collected by Cobb, a prominent physician and the first Black person to earn a doctorate in anthropology. During her tenure, part of her work involved training undergraduates to participate in research on the collection. Cobb had kept careful records, and students could study a person’s family, the place they’d grown up, and the conditions of their death.

“I would start off my undergraduates by having them investigate the identities of these individuals,” says Jackson. “It personalized the skeletons, in a way that we’ve lacked in many of the labs where African American material is. This was a human being, who had a life, who loved, who had all the frailties of every other human being, and deserves to be respected.”

Correction (April 20, 2022): A previous version of this story misstated the name of the American Association of Biological Anthropologists.