Centuries before COVID-19 brought the world to a screeching halt in March 2020, a tiny bacteria called Yersinia pestis–AKA the plague–killed roughly 25 million people throughout the Fourteenth Century alone as it spread across Eurasia, North Africa, and eventually the Americas for 500 years. Plague still exists today, particularly in the American west, and parts of Africa and Asia, but it can be treated with antibiotics.

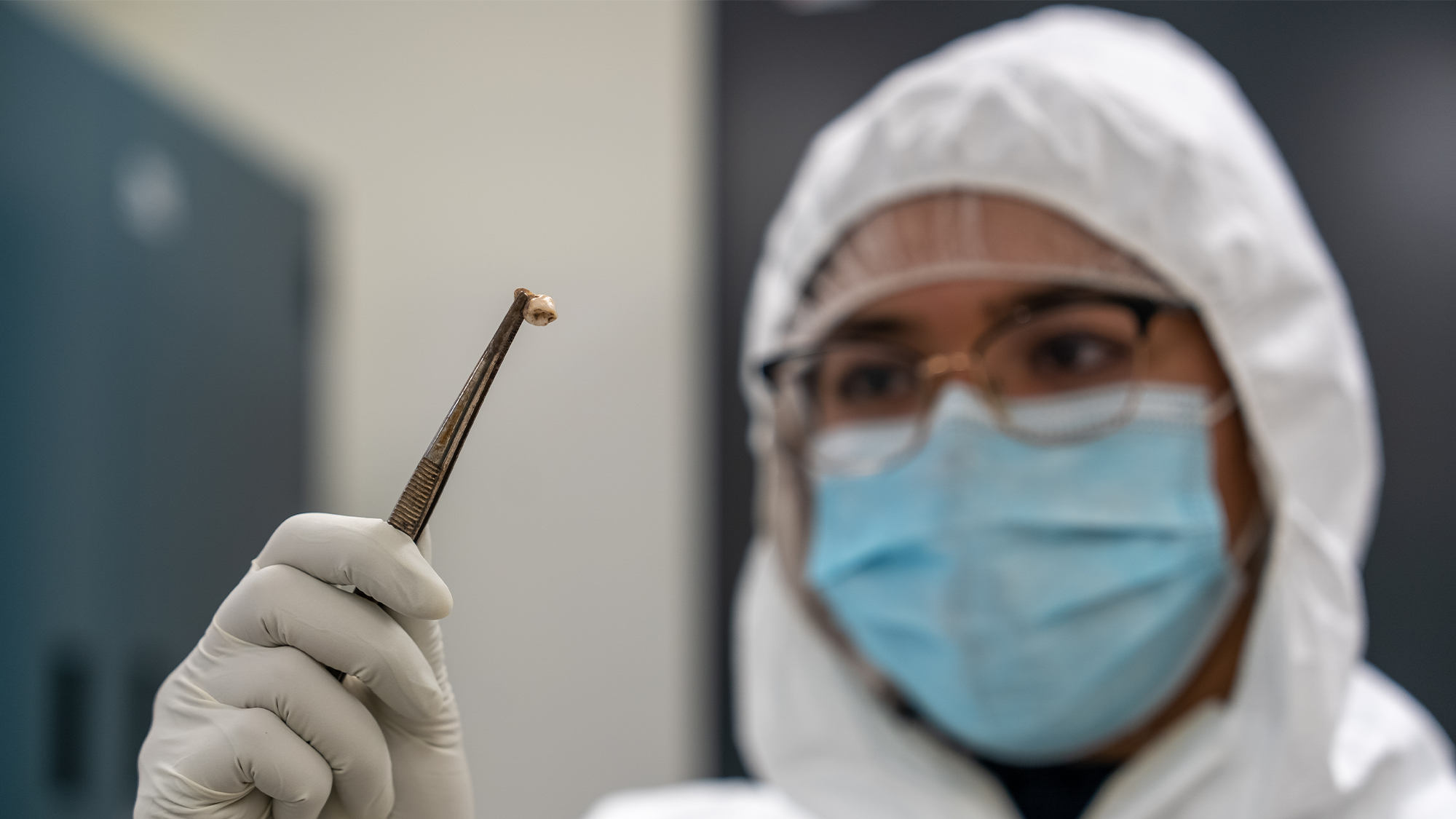

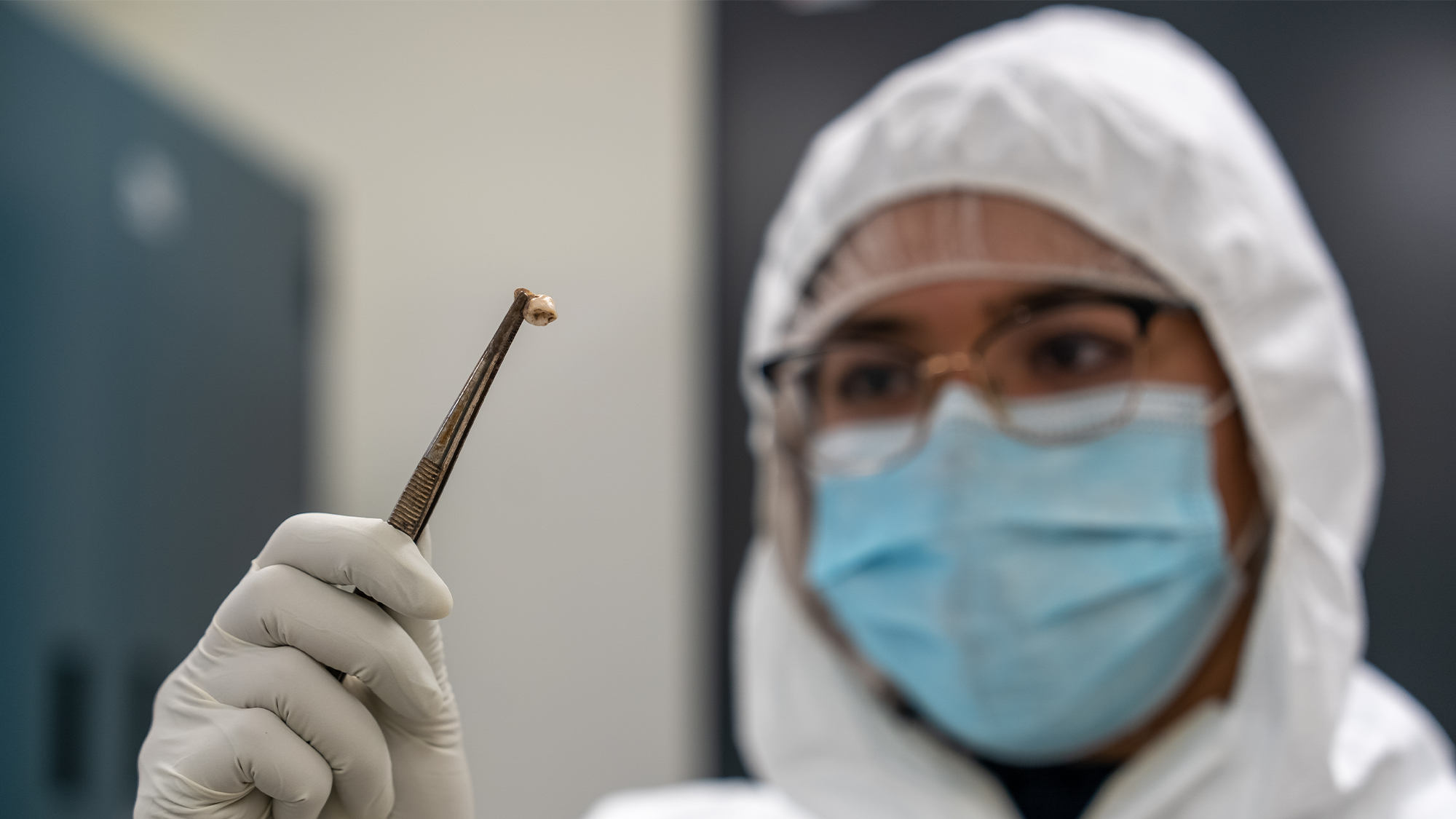

Now, a team of scientists studying the origins and evolution of the plague are using human teeth from Denmark to help them answer burning questions on how it arrived, persisted, and spread in Scandinavia.

[Related: What a 5,000-year-old plague victim reveals about the Black Death’s origins.]

Their study, published February 24 in the journal Current Biology, focused on a timeline of 800 years (1000 to 1800 AD) and used almost 300 samples collected at 13 archeological sites around Denmark. They used the samples from the teeth to reconstruct Yersinia pestis (Y. pestis) genomes that were present at the time. Teeth can preserve traces of blood-borne infection for centuries and proved to be a valuable resource for this kind of genetic detective work.

What they found is that the plague was reintroduced to the Danes in multiple ways over that time period via human movement.

“We know that plague outbreaks across Europe continued in waves for approximately 500 years, but very little about its spread throughout Denmark is documented in historical archives,” said study co-author Ravneet Sidhu, a graduate student at McMaster University’s Ancient DNA Centre, in a statement.

The analysis was conducted at McMaster and the team worked with historians and bioarchaeologists in Denmark and Manitoba, Canada to examine how the different strains of the plague that were present in Denmark during this period of time were related.

After reconstructing the genomes, the team then compared these older specimens with each other and their modern-day Y. pestis relatives. They found samples positive for plague in samples from 13 individuals who lived over a period of 300 years. From this pool, nine samples had enough genetic information to make evolutionary conclusions about how the plague persisted in Denmark, showing how urban and rural populations alike faced constant waves of the disease.

“The high frequency of Y. pestis reintroduction to Danish communities is consistent with the assumption that most deaths in the period were due to newly introduced pathogens. This association between pathogen introduction and mortality illuminates essential aspects of the demographic evolution, not only in Denmark but across the whole European continent,” said Jesper L. Boldsen, the skeletal collection curator and paleodemographer at the University of Southern Denmark, in a statement.

[Related: These skeletons might be evidence of the oldest known mercury poisonings.]

The analysis also showed that Y. pestis sequences from Denmark were interspersed with medieval and early modern strains that originated in other European countries, including the Baltics and Russia, instead of coming from a single Denmark specific cluster that reemerged from natural virus reservoirs over time.

“The evidence for plague in Denmark, both historical and archaeological, has been far more sparse than in some other regions, such as England and Italy. This study identified plague for the first time from medieval Denmark, therefore enabling us to connect the experience in Denmark to disease patterns elsewhere,” said co-author and University of Manitoba anthropologist Julia Gamble, in a statement.

The study proposes that the earliest known appearance of Y. pestis in Denmark dates back to 1333 in the southwestern town of Ribe around the time of the Black Death. It appeared in rural areas like Tirup and disappeared by 1649. Most of the places hit in Denmark were port cities, but one of the final outbreaks hit smaller rural sites in the central portion of the country that did not have access to water for transportation. The team believes that this suggests that humans were moving the pathogens around via rodents or lice.

“The results reveal new connections between past and present experiences of plague, and add to our understanding of the distribution, patterns and virulence of re-emerging diseases,” said Hendrik Poinar, a study co-author and director of the McMaster Ancient DNA Centre and an investigator with the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research, in a statement. “We can use this study and the methods we employed for the study of future pandemics.”