From curing genetic diseases to bringing back extinct species, the applications for gene editing tool CRISPR seem as limitless as the human imagination. And though the enzyme complex is more precise and easier to use than many of its predecessors, it occasionally still makes cuts at places in the genome that the researchers didn’t intend. Now a team of researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital has developed a new variation of CRISPR that eliminates these off-target modifications, according to a study published today in Nature. That could make many of the far-fetched applications—including those that require editing the human genome—more feasible more quickly.

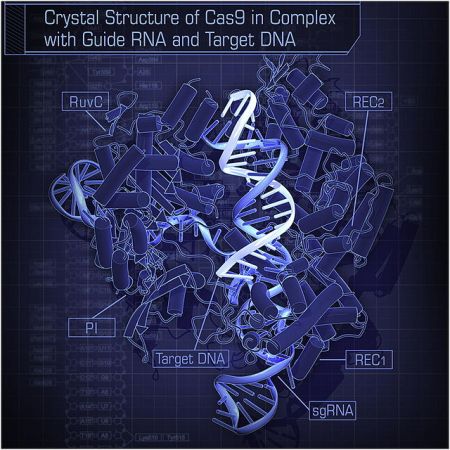

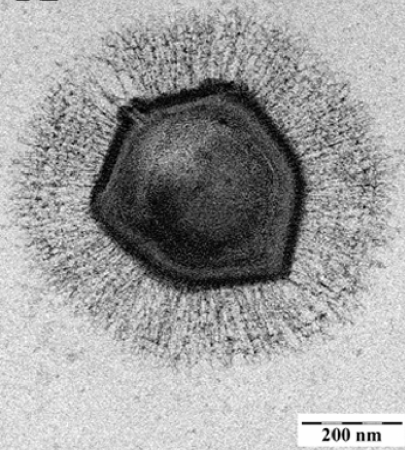

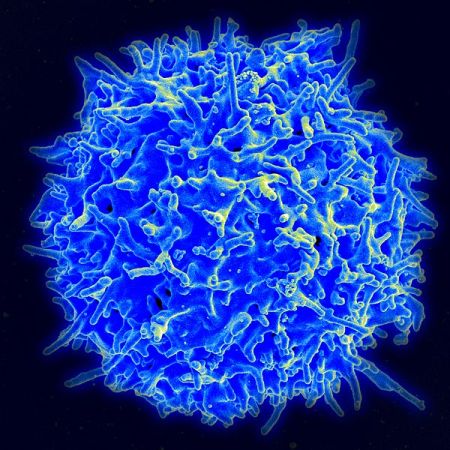

CRISPR contains two main components: guide RNA, which allows the enzyme to pick out a particular pattern of nucleotides from the entire genome, and the protein Cas9 that snips the strands of DNA. Occasionally, the guide RNA directs the enzyme to the wrong part of the genome, or to other repetitions of the nucleotides that weren’t the researchers’ intended target. And though these off-target cuts don’t happen often, a snip in just the wrong place could have disastrous effects on the organism. It’s one of the reasons why some experts are opposed to editing the human genome.

The researchers paid special attention to the interaction between the DNA and Cas9, the cutting protein. “Our previous work suggested that Cas9 might bind to its intended target DNA site with more energy than it needs, enabling unwanted cleavage of imperfectly matched off-target sites,” study author Vikram Pattanayak said in a press release. To tweak that interaction, the researchers altered the number of amino acids that Cas9 uses to bind to the DNA. After testing 15 different iterations, they found one version that produced no detectable off-target effects. They named it SpCas9-HF1. By adding more amino acids to the mix, the researchers found that they could extend the range of DNA that the protein targets, making it more useful to scientists.

This isn’t the first CRISPR variation that researchers have engineered. And it’s not even the first to resolve off-target modifications. As other variants make their way into the scientific community, researchers will figure out which work best, improving the quality of their experiments. With any luck, these precise enzymes will expedite these tests so that CRISPR’s possible applications can become realities.

![Is Your Pee The Right Color? [Infographic]](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/2JBOC76OMTD4JVI4XJXAAG4MK4.jpg?w=545)