Sadly, vitamins and supplements will not really keep the mosquitoes from biting you this summer, but scientists are still trying to figure out why the insects seem to love sucking some blood more than others.

[Related: How can we control mosquitos? Deactivate their sperm.]

In a small study published May 10 in the journal iScience, a team of researchers looked at the possible effects that soap has on mosquitoes. While some soaps did appear to repel the bugs and others attracted them, the effects varied greatly based on how the soap interacts with an individual’s unique odor profile.

“It’s remarkable that the same individual that is extremely attractive to mosquitoes when they are unwashed can be turned even more attractive to mosquitoes with one soap, and then become repellent or repulsive to mosquitoes with another soap,” co-author and Virginia Tech neuroethologist Clément Vinauger said in a statement.

Soaps and other stink-reducing products have been used for millennia, and while we know that they change our perception of another person’s natural body odor, it is less clear if soap also acts this way for mosquitoes. Since mosquitoes mainly feed on plant nectar and not animal blood alone, using plant-mimicking or plant-derived scents may confuse their decision making on what to feast on next.

In the study, the team began by characterizing the chemical odors emitted by four human volunteers when unwashed and then after they had washed with four common brands of soap (Dial, Dove, Native, and Simple Truth). The odor profiles of the soaps themselves were also characterized.

They found that each of the volunteers emitted their own unique odor profile and some of those odor profiles were more attractive to mosquitoes than others. The soap significantly changed the odor profiles, not just by adding some floral fragrances.

“Everybody smells different, even after the application of soap; your physiological status, the way you live, what you eat, and the places you go all affect the way you smell,” co author and Virginia Tech biologist Chloé Lahondère said in a statement. “And soaps drastically change the way we smell, not only by adding chemicals, but also by causing variations in the emission of compounds that we are already naturally producing.”

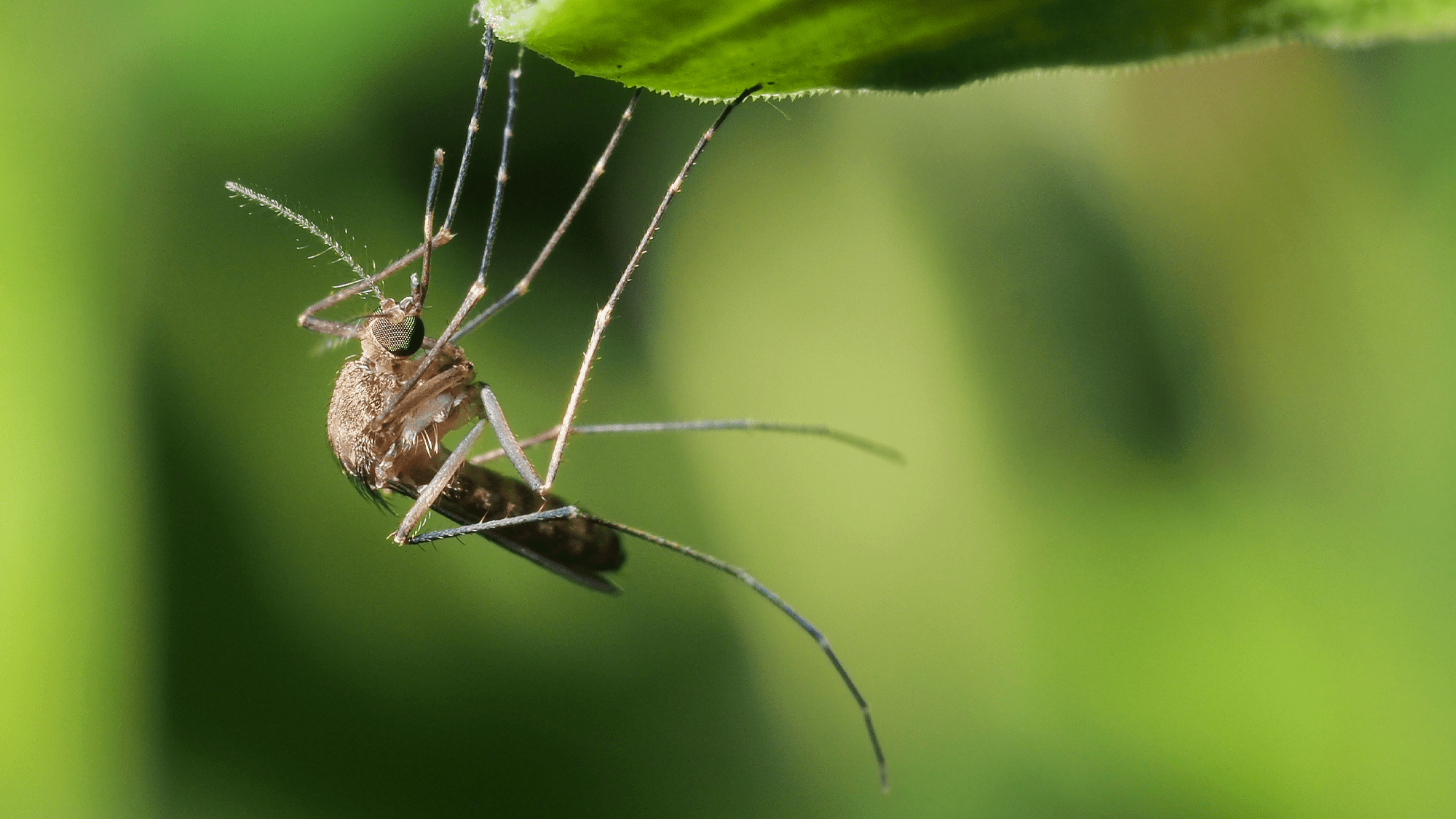

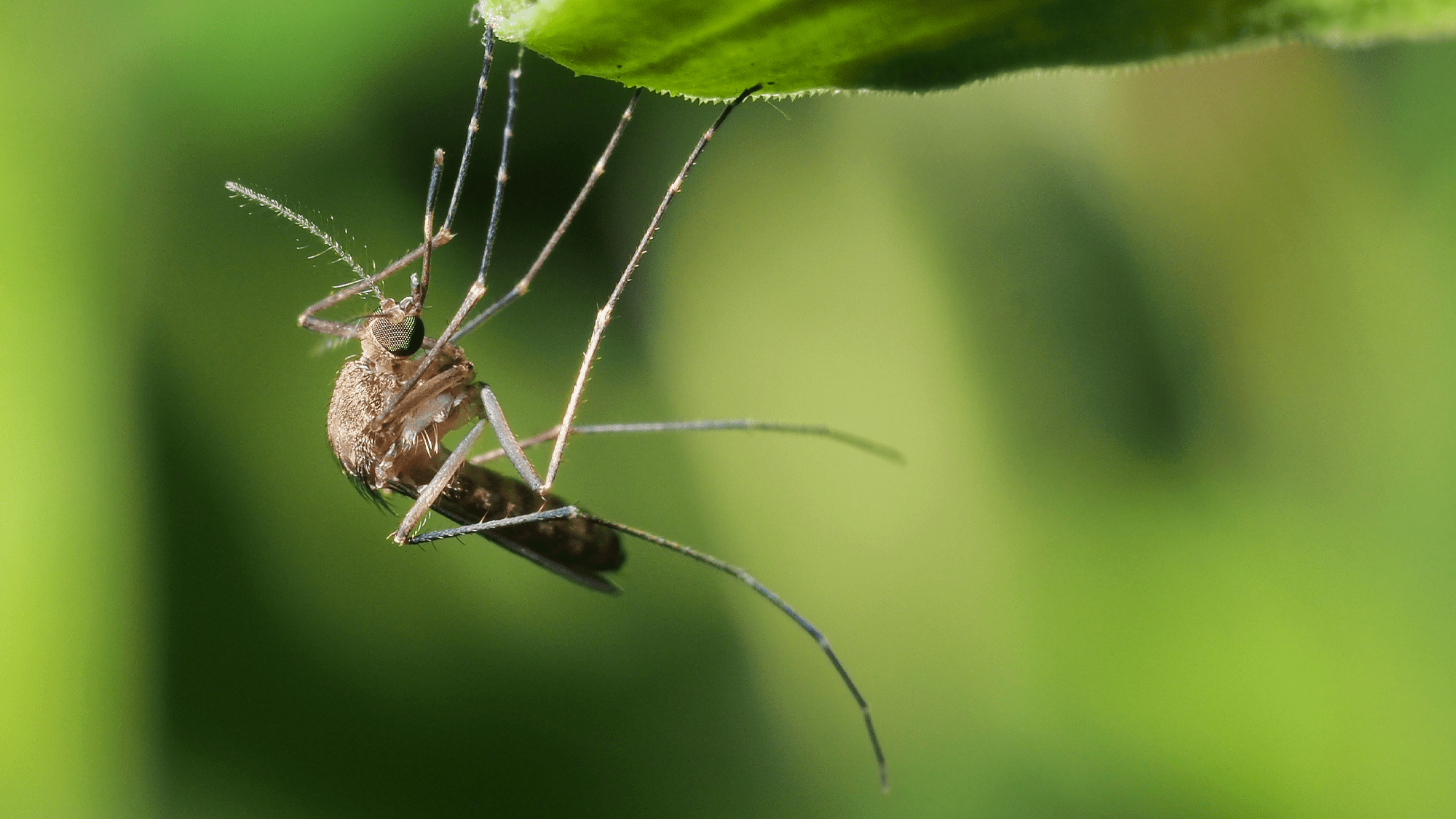

The researchers then compared the relative attractiveness of each human volunteer–unwashed and an hour after using the four soaps–to Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. These mosquitoes are known to spread yellow fever, malaria, and Zika among other diseases. After mating, male mosquitoes feed mostly on nectar and females feed exclusively on blood, so the team exclusively tested the attractiveness using adult female mosquitoes who had recently mated. They also took out the effects of exhaled carbon dioxide by using fabrics that had absorbed the human’s odors instead of on the breathing humans themselves.

[Related from PopSci+: Can a bold new plan to stop mosquitoes catch on?]

They found that soap-washing did impact the mosquitoes’ preferences, but the size and direction of this impact varied between the types of soap and humans. Washing with Dove and Simple Truth increased the attractiveness of some, but not all of the volunteers, and washing with Native soap tended to repel mosquitoes.

“What really matters to the mosquito is not the most abundant chemical, but rather the specific associations and combinations of chemicals, not only from the soap, but also from our personal body odors,” said Vinauger. “All of the soaps contained a chemical called limonene which is a known mosquito repellent, but in spite of that being the main chemical in all four soaps, three out of the four soaps we tested increased mosquitoes’ attraction.”

To look closer at the specific soap ingredients that could be attracting or repelling the insects, they analyzed the chemical compositions of the soaps. They identified four chemicals associated with mosquito attraction and three chemicals associated with repulsion. Two of the mosquito-repellers are a coconut-scented chemical that is a key component in American Bourbon and a floral compound that is used to treat scabies and lice. They combined these chemicals to test attractive and repellent odor blends and this concoction had strong impacts on mosquito preference.

“With these mixtures, we eliminated all the noise in the signal by only including those chemicals that the statistics were telling us are important for attraction or repulsion,” said Vinauger. “I would choose a coconut-scented soap if I wanted to reduce mosquito attraction.”

The team hopes to test these results using more varieties of soap and more people and explore how soap impacts mosquito preference over a longer period of time.