The Arctic Circle hasn’t always been so, well, arctic. About 52 million years ago, during the early Eocene Epoch, it was still mostly dark for half the year like it is today, but it was quite a bit warmer, more humid. The Arctic of years past had a boreal forest ecosystem similar to what is seen in Canada and parts of Russia today. It was even home to many early Cenozoic era vertebrates, including ancient crocodiles and camels.

It was also home to at least two near-primate sister species, Ignacius mckennai and I. dawsonae. Scientists have found new specimens that are the oldest near-primate remains that have been found north of the Arctic Circle to date. The specimens and what we could learn from them are described in a study published January 25 in the journal PLOS ONE.

[Related: Adolescent chimpanzees might be less impulsive than human teens.]

“No primate relative has ever been found at such extreme latitudes,” study co-author Kristen Miller, a doctoral student with the University of Kansas’ Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum, said in a statement. “They’re more usually found around the equator in tropical regions.”

A process called phylogenetic analysis, which uses branching diagrams to show the evolutionary history and relationships of a species, helped the team to figure out how the fossils from these newly found species were related to those found in modern-day mid-latitude locations in North America.

The specimens were found on Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, Canada, near the northwest coast of Greenland. They were found in sediment that dates back to the warmer Eocene, and studying this time period could foretell how Earth’s ecosystems will fare in coming years due to climate change.

According to Miller, both species are descended from a common northbound ancestor who possessed a spirit “to boldly go where no primate has gone before.”

The intense periods of darkness of the Arctic Circle may have triggered both of these species to evolve a surprising trait compared to their other primate relatives: more robust teeth and jaws. The team believes that it was much more difficult to find food during dim winter months. The Arctic primate relatives likely had to eat tougher harder material like nuts and seeds, as opposed to softer snacks like fruit, which could have impacted their unique dentistry.

“A lot of what we do in paleontology is look at teeth—they preserve the best,” said Miller. “Their teeth are just super weird compared to their closest relatives. So, what I’ve been doing the past couple of years is trying to understand what they were eating, and if they were eating different materials than their middle-latitude counterparts.”

[Related: There Used To Be Freaking Camels In The Arctic.]

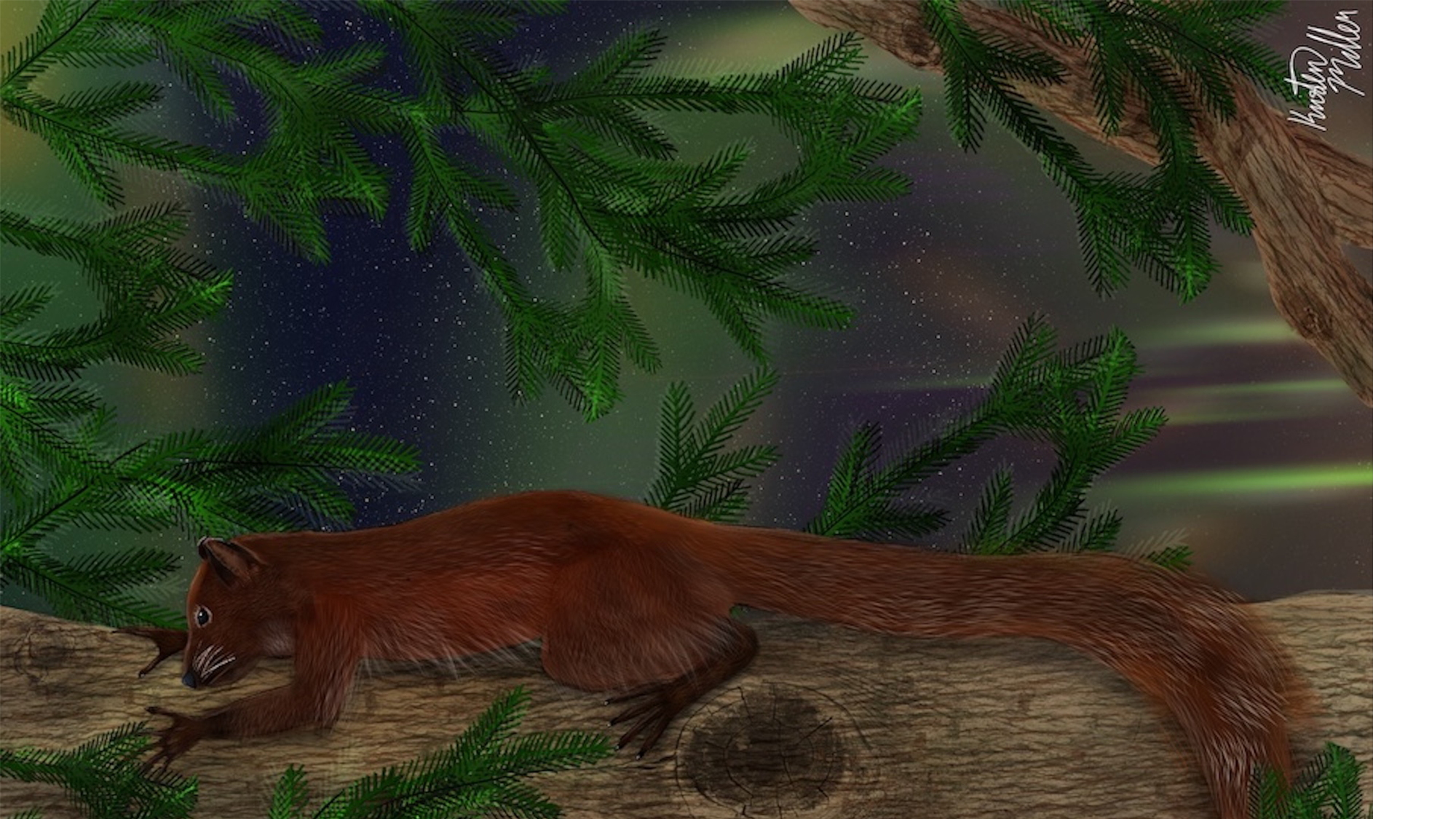

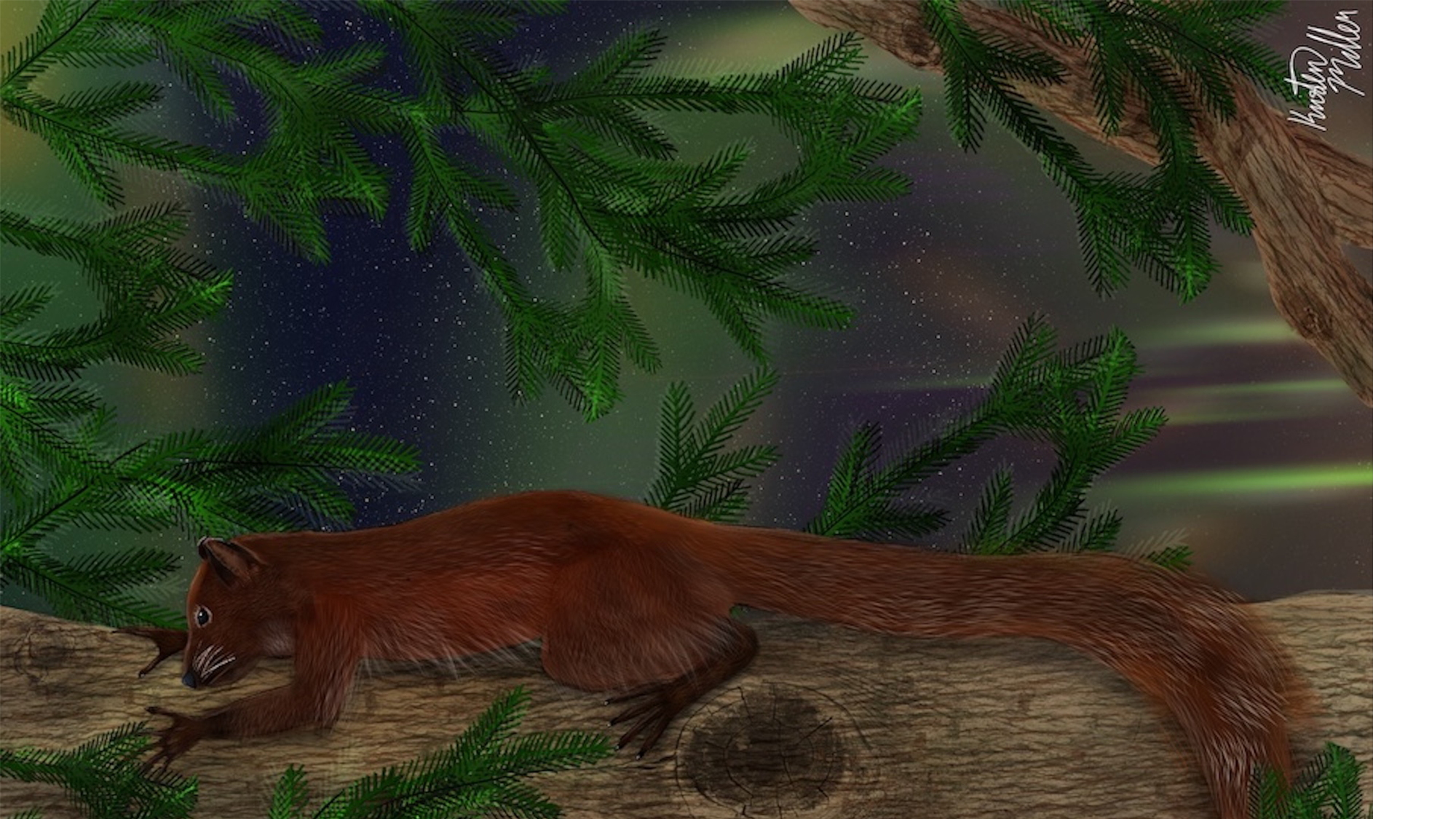

The closest relatives of these species were likely a group of primates called plesiadapiforms, which were found further to the south during this time period. The northern primates were bigger than the southern ones, but all of them appear to be around rodent size.

“Some plesiadapiforms from the midlatitudes of North America are really, really tiny,” said Miller. “Of course, none of these species are related to squirrels, but I think that’s the closest critter that we have that helps us visualize what they might have been like. They were most likely very arboreal—so, living in the trees most of the time.”

The team believes that some of the adaptations that Arctic near-primate species took during another period of global warming demonstrates how some animals could evolve new traits–lessons that animals could be undergoing due to climate change today.

“I think probably what it says is [that] primates’ range could expand with climate change or move at least towards the poles rather than the equator,” said Miller. “Life starts to get too hot there, perhaps we’ll have a lot of taxa moving north and south, rather than the intense biodiversity we see at the equator today.”