Around 15 million years ago, Australia was once a lush rainforest. An ancient river meandered in the southeast, gradually carving out a lake from one of the river bends. Carcasses of fish and other inhabitants were often washed into the pool, perhaps when the river flooded, but the oxygen-starved waters thwarted riverine scavengers from reaching these easy meals. Dissolved iron in the water eventually precipitated, burying the biological evidence at the bottom of the lake for eons—until a modern-day farmer, Nigel McGrath, discovered these iron-rich fossils in what is now New South Wales.

The fossil trove, known as McGraths Flat, covers only about half the area of a football field, yet boasts one of the most impressive records of prehistoric rainforest life. Since the flat was discovered, paleontologists have catalogued more than 2,000 fossils from the Miocene, an epoch that stretches from 23 to 5 million years ago. Published in the journal Science Advances last Friday, paleontologists at the Australian Museum Research Institute reveal a cornucopia of new fossil finds that peeks into the region’s past. The region’s unique paleontological specimens add a missing piece to the fossil record that shed light on how the ancient ecosystem shifted when the Australian continent transformed from an arboreal landscape to the grassy drylands it is today.

[Related: Now paleontologists know what colors graced these 200-million-year-old butterfly wings]

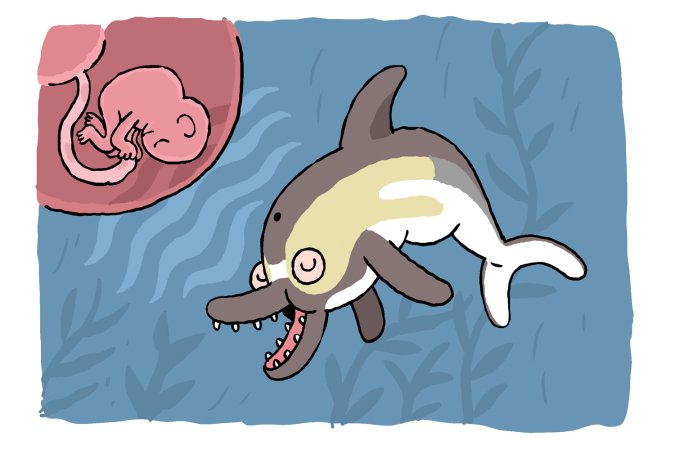

Unlike other Miocene fossil sites in Australia that are peppered with the bones of large vertebrates, McGraths Flat contains remnants of flora and soft-bodied fauna, which are typically more challenging to preserve over the ages. The fossils’ abnormally high quality of preservation captures the delicate bodily features of the creatures that once thrived. Traces of pigment sacs still lurk in some of these relics, hinting at the hues the animals may have once donned back in their heyday. Several fossilized subjects are caught frozen in action or interacting with other species, such as parasites piggybacking off fish hosts, giving a glimpse into past dynamic ecological communities and relationships. Moreover, the iron in the fossils is a boon—the presence of this mineral makes modern imaging techniques easier, as researchers don’t need to irreversibly alter the specimens before scrutinizing them under a microscope.

“We can see into these ecosystems like never before,” co-lead author on the study and paleontologist Matthew McCurry of the Australian Museum Research Institute tells National Geographic. His team’s study provides a glimpse into the complex lifeforms crawling, swimming, buzzing, or photosynthesizing—flourishing in a bygone jungle of a bygone era.