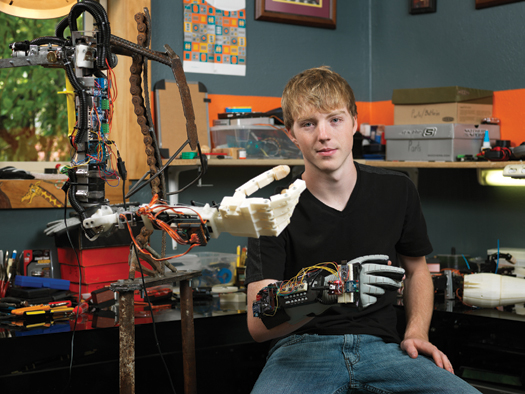

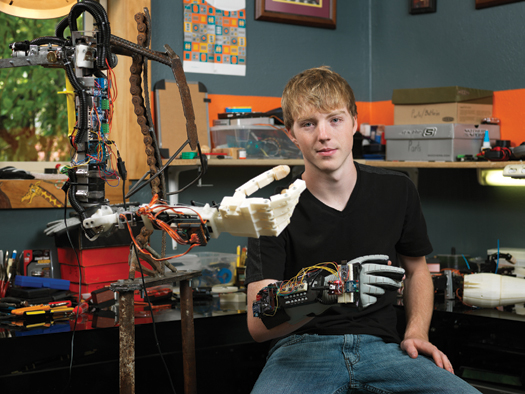

Two summers ago, Easton LaChappelle thought it would be fun to build a robotic arm controlled wirelessly using a glove. LaChappelle, then 14, knew nothing about electronics, programming, or robots—but he was bored and desperate for a challenge. So over the next couple of years, the teen, now a high school junior, toiled in his cramped bedroom workshop in Mancos, Colorado, ironing out the details. In time, he emerged with a robo-arm operated by a gaming glove—and his mind.

LaChappelle began his bionic quest by scouring online forums and tutorials to glean as much know-how as he could about sensors, motors, and coding. His first model won him third place at the state science fair in 2011, but its fingers, made of flimsy electrical tubing, could not grasp anything heavy.

Unsatisfied, LaChappelle started over. He designed a new hand with computer modeling software, and then asked MakerBot Industries in Brooklyn, New York, to print the plastic “bones.” The new hand had human-like digits with multiple joints and a thumb that could bend inwards. Small electric motors in the wrist could curl the fingers by pulling a piece of ligament-like fishing line through each digit to its fingertip.

But the stretchy fishing line loosened up over time. LaChappelle’s mother, a former jeweler, suggested using nylon-coated steel wire instead. The wire could close the fingers but proved too rigid to recoil them, so LaChappelle rigged tiny dental rubber bands leftover from his awkward, brace-faced years into faux tendons for the joints. “The rubber bands provide a kind of spring-back mechanism,” he explains.

To control his robo-limb, LaChappelle modified a 1980s-era Nintendo Power Glove to convert real hand movements into robotic motion. Next, he made a brain-based controller by hacking parts of a headset from the board game Mindflex, which can read a player’s brainwaves. Simply by concentrating, LaChappelle says he can open and close the robo-hand.

The glove-based system earned him second place at an international science fair in 2012, and his parents rewarded him with his own 3-D printer, now housed in his bedroom closet. For his next goal, LaChappelle plans to evolve the current robo-arm into an inexpensive yet highly capable prosthetic. “I’m going to keep going and trying to make it better and better,” he says.

See how it works on the next page.

HOW IT WORKS

BUST A MOVE

LaChappelle built a skeletal frame out of scrap metal with industrial chain for a spine. A custom-built robotic arm rotates the hand at the wrist and bends at the elbow and shoulder. Two battery-powered, geared DC motors can lift the arm 90 degrees and lower it down.

MIND GAMES

Our minds emit faint frequencies of electrical energy called brainwaves, which doctors use to analyze everything from seizures and coma to sleep and focus. LaChappelle hacked Mattel’s focus-measuring Mindflex headset by writing software to convert the device’s data for his robo-hand. As a wearer’s brainwaves shift above or below a set frequency, the hand opens or closes.

SENSITIVE GRIP

When he’s not using the headset, LaChappelle controls his robotic limb with a 1989 Nintendo Power Glove. Flex sensors in the glove provide data for the robotic fingers to mirror his motions. To feel the robo-hand’s grip, he added eraser-size force sensors to the robotic fingertips. A wireless radio relays this data to the Power Glove and activates a cellphone’s vibrating motor: The stronger the squeeze, the more vibration he feels in the glove.

BUILDING A ROBOT ARM

Time: 1 year

Cost: $900

Warning: We review all our projects before publishing them, but ultimately your safety is your responsibility. Always wear protective gear, take proper safety precautions, and follow all laws and regulations.