Up until recently, anyone suffering from high cholesterol had a fairly easy option to improve health. All they needed was a prescription for a group of chemicals known as statins. For decades, this was the go-to drug to cost-effectively keep low density lipoprotein (LDL) levels in check and prevent the onset of cardiovascular disease. Although this view has changed somewhat with the FDA providing advice on the potential risks associated with their use, the number of people taking these drugs continues to be high.

While the majority of research on statins appears to be focused solely on cholesterol, researchers have examined other potential benefits. Some include the formation of new blood vessels and an improvement in immune, bone and central nervous systems . But one of the most studied has been the antimicrobial effects of these drugs. For some reason, their inclusion seems to help the chances of infection prevention and control.

One of the first mention of statins as antimicrobials came out in 2001 when their use appeared to help reduce the mortality rate in people suffering from sepsis. The effect was so pronounced, the drugs were considered as potential therapy for this life-threatening disease. As the evidence grew, so did the experiments in the laboratory. In 2008, the effect of statins on one of the causes of sepsis, Staphylococcus aureus, was shown. It even had an effect on the antimicrobial resistant version, Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

With the knowledge of the effects during the most critical infections, researchers sought to identify whether the drugs could help those who might not be at immediate risk. In 2014, the drug was even suggested to be an important part of cardiovascular disease reduction by simply preventing microbial-based inflammation. The reason stemmed from the ability of the drugs to stop the development of S. aureus colonies, biofilms, which is a critical step in the development of infections of the skin and the blood.

But S. aureus wasn’t the only target. Other studies have revealed the antimicrobial effects against pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the influenza virus, and the worm, Schistosoma mansoni. In each case, the drugs seemed to have a direct effect on the microbe to keep it from causing an infection or at least allowing it to worsen.

There is another potential protective mechanism against pathogens. This time, the target is yeast, particularly Candida. This particular species is known to cause both skin infections as well as the bloodborne infection called candidemia. Without immediate intervention, the latter can be life-threatening.

The first hints of yeast-blocking activity came in 2010 when statins appeared to help reduce the mortality rate. This was echoed in 2013, although the results were not conclusive. Though there was apparently some benefit, the actual contribution of the drug could not be determined.

Now there is evidence statins have the same anti-biofilm effect on yeast as they do on bacteria. Last week, a Brazilian team of researchers published their analysis of the effects of the drugs on Candida and another genus, Cryptococcus. Their results suggest the previous results were actually due to the drug and may offer hope for the development of novel therapies.

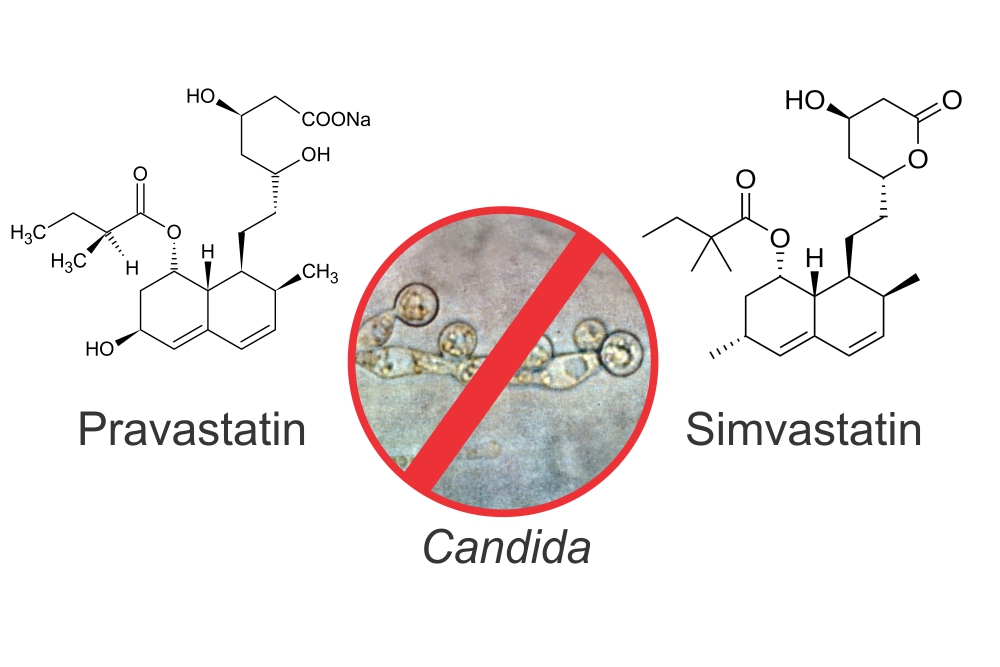

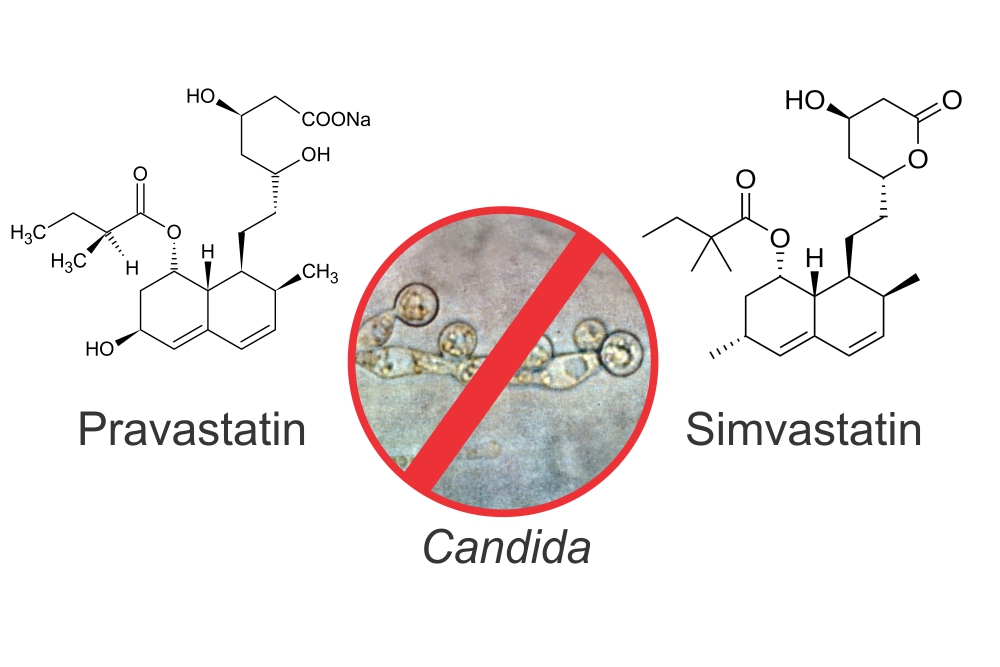

The group used 51 strains of Candida and 25 strains of Cryptococcus for the test. As for the statins, three were chosen, simvastatin, atorvastatin, and pravastatin. The team also included antifungal drugs such as amphotericin B, itraconazole and fluconazole to act both as individual controls and also as additive for combinatorial therapy.

The testing followed to particular paths. The first attempted to determine the effect of statins on individual cells, called planktonic. The second focused on the formation of biofilms. If all worked out well, the drugs on their own would both kill the yeast and consequently prevent biofilm formation. In case this didn’t work, the combination option was expected to be effective.

The results were somewhat surprising. Out of the three statins, simvastatin came out on top. It killed Candida planktonic cells and also prevented biofilm formation. The effect was solely due to the drug as combinations with antifungals had no improved effect. The authors suggested the drug prevented the yeast from being able to properly function by both causing defects in the outside membrane as well as the internal mitochondria.

When it came to Cryptococcus, the results were similar. The only difference was a noticeable synergy between simvastatin and amphotericin B. The authors believed this was due to the different routes of antimicrobial activity working together although an exact mechanism wasn’t elucidated.

The authors concluded simvastatin was by far the best potential antifungal statin and that further research would be well worth following. As to the reason why this particular drug was better than the other two, there was no explanation. Yet, the answer may be found in the original nature of the statins.

Although simvastatin, atorvastatin, and pravastatin are synthetic, they are based on a class of naturally-derived molecules found in fungus. Simvastatin is based on a molecule lovastatin derived from Aspergillus terreus. Pravastatin is a modification of a molecule from Penicillium citrinum. Both these species have the ability to fight off yeast in the wild and as a result the derived statins may still harbour the antifungal activity. As for atorvastatin, it a completely synthetic molecule developed through molecular modelling. As a result, the antimicrobial activity may not have been included in the final product.