Human beings are generally okay with buck heads. We hang them on our walls, set bouquets on them and stick them in bowties. But when it comes to testing these cervids for signs of fatal disease, some people would rather avoid decapitation entirely.

So Claudio Soto, a neurology researcher at McGovern Medical School, created a blood test for chronic wasting disease (CWD), an untreatable deer ailment similar to mad cow that is spreading across the U.S. In the last month, the disease reached new counties in Michigan and Montana.

The two existing USDA-approved CWD tests require brain and lymph node tissue, which is impossible to retrieve from a live deer. And testing for CWD before consumption is crucial. The disease has not yet been documented in humans, but the CDC advises against eating meat from infected animals. In July, Stefanie Czub, a scientists with the Canadian food inspection agency, presented evidence that macaque monkeys suffered from CWD after eating infected deer and elk. “It’s spreading in numbers, and geographically,” says Soto. “It’s an epidemic that is growing. And it’s dangerous because we don’t know if it can be transmitted to the human population.”

Soto launched Amprion Inc to market his blood-testing technique, and also allowed the company Sustainable Agriculture and Wildlife Corp, LLC to use it. They started providing the first live blood test in August 2016. According to the instructions, hunters must collect blood from a “freshly harvested” deer and add it to the SAWCorp kit. There’s only one problem.

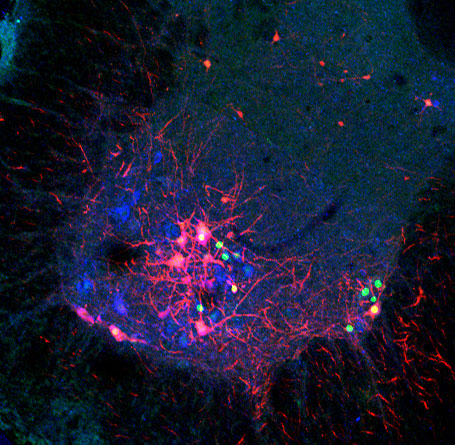

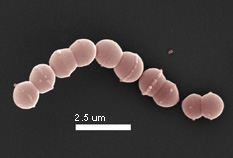

The contagious misfolded proteins, called prions, that cause CWD don’t usually lurk in the blood, according to the USDA. They squirm around in the brain, spinal cord, eyes, spleen, tonsils, and lymph nodes, transforming their fellow macromolecules into infectious zombies. Some prions leak into other parts of the body and into the animal’s waste, according to Soto, and his test has the special amplification techniques it takes to find them.

The USDA has stated that it will not accept any results from this test, called the PMCA prion blood test. “While APHIS [Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service] supports emerging technologies, no company has submitted the data needed for APHIS to evaluate the PMCA prion blood test,” says the statement. “In addition, APHIS is aware of no peer-reviewed scientific publications that establish the efficacy of PMCA as a detection method for CWD in cervid blood.”

The implementers of the test tell a different story. Pete Snyder, the director of National Agricultural Genotyping Center—the lab that performs the CWD test for SAWCorp—says that the USDA has restricted their access to deer blood, making it impossible to submit data for approval. The lab members eventually resorted to using samples from their own hunting expeditions, and even from roadkill.

For now, Snyder says, the lab has yet to receive any customer samples for processing, although SAWCorp manager Blake Ashby says they have sold a few hundred testing kits this season. But the hunting season is still fresh, and Snyder believes their results will speak for themselves. His dream is to complete a side-by-side comparison between the two USDA-approved tests and his own. “If it doesn’t stand up under fair scrutiny, then I will back down,” he says

A lack of USDA approval does not prevent the lab from performing the test for hunters, but it does restrict SAWCorp’s access to deer farmers. “The real test, to my way of thinking, is the deer breeder and the deer rancher who wants to make sure his herd is CWD free,” says Snyder. “And that’s where the beauty of a live blood test would come in.” In Texas alone, the hunting industry brings in $2.2 billion, and gamespeople can pay up to $25,000 to shoot a single head one of the state’s massive deer ranches. Now those herds are at risk. In February, Texas officials announced the state’s first case of CWD in a wild whitetail deer.

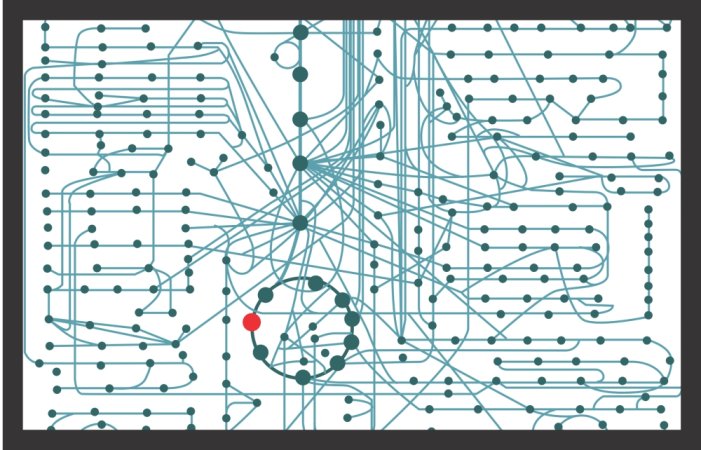

And the disease isn’t only a problem in Texas. It’s been found in 21 states so far, and experts expect the count to keep growing. “As fast as the disease is spreading right now, it won’t be surprising if five to 10 years from now every state has CWD,” says Kip Adams, a biologist at the Quality Deer Management Association.

But the blood test could have implications far beyond protecting our access to venison. Soto, the neurologist who developed the technique now used by SAWCorp, researches Alzheimer’s and other brain-related illnesses. Snyder hopes that the implementation of the CWD blood test will help labs hone their methods for detecting other neurodegenerative diseases in humans and animals.

Soto hopes his test will be approved to for prion diseases in every species, as well as other neurodegenerative illnesses. “The technology’s there, we just need more work to validate the technique,” he says. “This looks very promising, and we are applying the principles from this test to many other diseases.”

But while some are excited about the test’s potential, others are wary of the results it boasts. Hunters will see the SAWCorp test advertised in hunting magazines, and may not understand that the method is still relatively unproven. “The company doesn’t say that USDA endorses their product, however, their ad is cleverly worded at the bottom to implicate the USDA,” says Laurie Ristino, a law professor and Director for the Center for Agriculture and Food Systems at Vermont Law School.

Even USDA-approved tests, which require lymphoid and brain tissue, can’t prove for certain that an animal does not have CWD. Currently, the three outcomes of the USDA-approved CWD tests are “positive, “not detected,” or “unsuitable,” according to Jeannine Flagle, a biologist for the Pennsylvania Games Department who wrote a blog post on this topic.

With the disease spreading and hunters becoming aware of the problem, the USDA may not get much say in what test consumers use. “We have surprising number of calls from wives who are worried about their husband’s harvest,” says Shelby. Troubled by all of the uncertainties swirling around CWD and its testing methods, it’s hard to blame hunters for jumping on what seems to be an easy solution.