It’s long been accepted by physics that nature has supplied us with four fundamental forces. Gravity holds the planets and galaxies together, and the electromagnetic force holds us and our molecules together. At the smallest level are the two other forces: the strong nuclear force is the glue for atomic nuclei, and the weak nuclear force helps some atoms go through radioactive decay. These forces seemed to explain the physics we can observe, more or less.

According to some Hungarian physicists, there may be a fifth force we don’t even know about.

Attila Krasznahorkay and his group at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences’s Institute for Nuclear Research in Debrecen, Hungary, initially published their new discovery last year, reports Nature Magazine, but no one paid much attention; that is, until now. A group of theoretical physicists led by Jonathan Feng at the University of California, Irvine, took a look at the Hungarian group’s results, and found this new force didn’t seem to break any existing laws of physics. The numbers checked out. Feng’s results published their results on the arXiv preprint server last month.

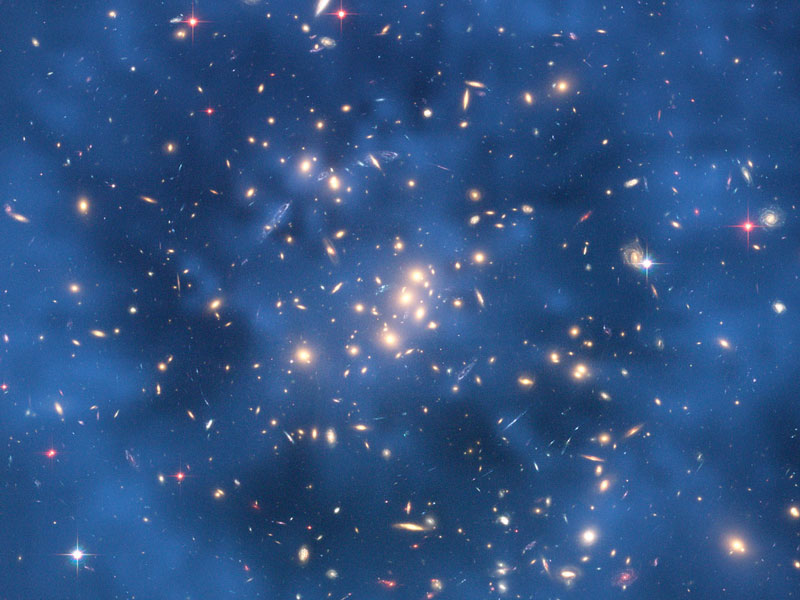

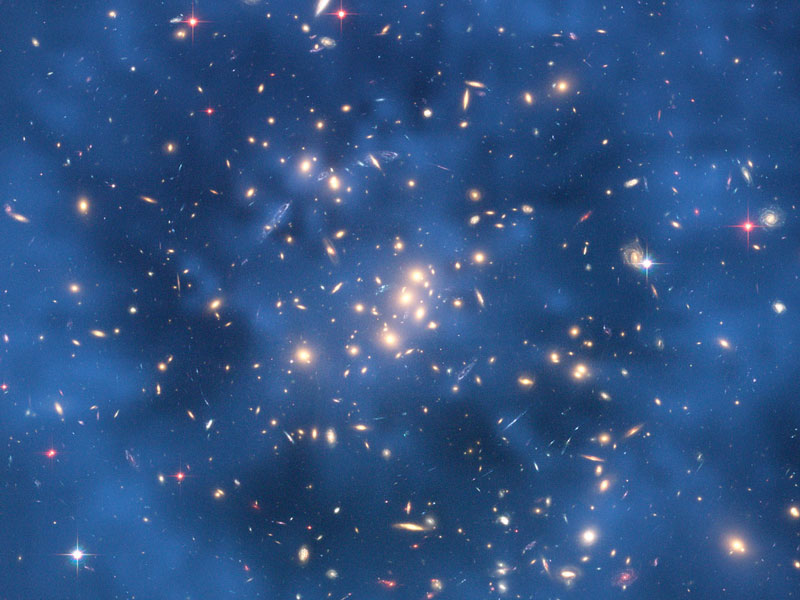

A new force would not be completely unexpected. The stuff we can see and touch only makes up about a fifth of the universe’s mass, while dark matter fills out the rest. Dark matter can feel gravity but not electromagnetism, which is why we can’t see or touch it, since our sight, touch, and most of our science experiments detect stuff using the electromagnetic force.

Physicists aren’t sure whether or not there are some unknown forces that only affect dark matter. If there were, dark matter might “clump,” and some physicists think gravity from clumpy dark matter could even be behind the comet that made the dinosaurs go extinct.

The Hungarian group found their new force while looking for a “dark photon,” light that only impacts dark matter. They hit a strip of lithium with protons, the lithium sucked up the protons to become an unstable version of beryllium, which threw up pairs of electrons and positrons, the electron’s antiparticle partner. When the protons hit the lithium at a certain angle, 140 degrees, out came way more electrons and positrons than the Hungarians were expecting. They think all that excess stuff could be from a new particle 34 times heavier than the electron, and a hint that maybe there’s a new force lurking somewhere.

Nature reports that other physicists seem skeptical, but are excited about the new force. Still, researchers at the Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility in Newport News, Virginia, CERN, and other labs are trying to see if they can recreate the Hungarian team’s results in their own experiments.