About one in five Americans believes that the Sun revolves around the Earth. And if you happened to collect 12 of those people on a jury in which the orbiting properties of our solar system were up for debate, the headlines about the verdict would probably read “Earth revolves around Sun, declares American jury.” But that wouldn’t make it true.

And equally, headlines that read “Italian court rules mobile phone use caused brain tumour” don’t mean that mobile phones cause brain tumors (or tumours). It means some uninformed people wanted to award money to a guy who can’t hear anymore because the operation that saved his life also removed his acoustic nerve. So if you stop reading this article right now and retain nothing else, remember this: cellphones do not cause cancer. End of story.

Now for the rest of the story.

The evidence against

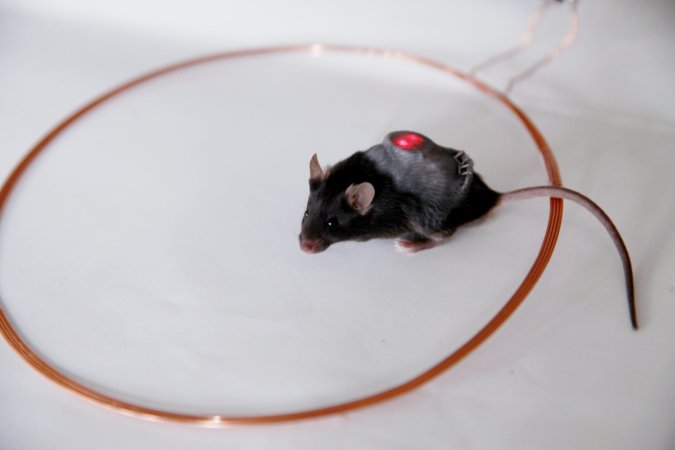

In this corner of the ring, we’ve got virtually every study—mouse, rat, or human—that’s ever been done on the matter. If mobile phones did cause cancer, you’d expect to see a significant spike in brain cancer rates following the massive increase in cell phone usage in the last decade or so. And yet there’s been no change. No wait, that’s not true, there has been a change—brain cancer rates are actually decreasing. You’d also expect to see more tumors in parts of the brain that absorb high amounts of radio waves, which is how people claim phones cause cancer. You actually see the opposite: areas that absorb radio waves have fewer tumors, not more.

Also, people who spend a lot of time on their cell phones aren’t more likely to get brain tumors than their Luddite neighbors. Children who have and use mobiles aren’t at a higher risk of cancer. Radio waves aren’t even capable of damaging DNA. The list could keep going (and it does, if you meander on over to the National Cancer Institute’s website).

The “evidence” for

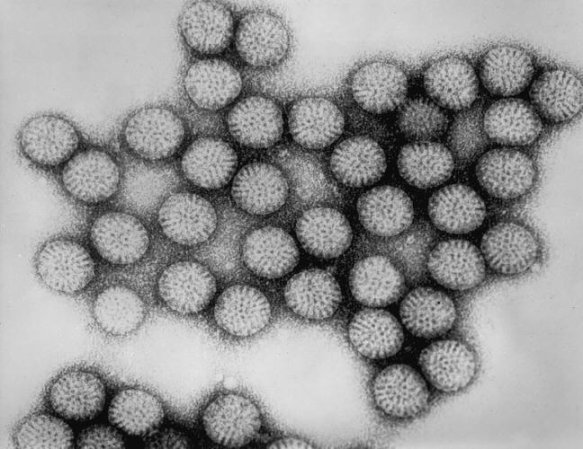

So why, with all this evidence, does the International Agency for Research on Cancer classify radio waves as “possible carcinogens”? Because, as IARC itself put it, “The studies to date do not permit to rule out a relationship between mobile phone use and risk of brain cancer although the evidence is limited.” That shadow of a doubt is enough for them to put cell phones on their Group 2B list of possible human carcinogens, which includes items for which “there is limited evidence of carcinogenicity in humans and less than sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in experimental animals.”

There are lots of scary-sounding chemical names on the list alongside radio waves from mobile phones, but you might find one in particular more recognizable: aloe vera. You know—the stuff you rub on your sunburn to soothe it or use as a hydrating face mask. That cooling gel is, according to IARC, a possible human carcinogen.

The problem is that science can’t prove a negative, even with infinite numbers of flawless studies. There will always be some tiny possibility that somehow we’re missing something. That’s why IARC doesn’t have a list of things known to not cause cancer.

Instead, even if there are just a handful of flawed studies that suggest there might be some very minor link between a substance and cancer, IARC is going to list that substance. When IARC published its findings on radio waves, two epidemiologists wrote in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute that the IARC’s summary article “reads like a textbook on how the biases and flaws that may creep into cell phone case–control interview studies may render results virtually uninterpretable.” But IARC’s lists have real world consequences—misunderstandings about their lists have confused court cases before now, too.

Other major health organizations aren’t so cautious. The American Cancer Society says that there’s no good evidence that cell phones cause cancer. The National Cancer Institute agrees, as do the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the Food and Drug Administration, the Federal Communications Commission, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These are the agencies tasked with considering whether potential risks cause actual threats. IARC is kind of like the first line of defense, whose job is to consider even the faintest evidence, so that other organizations can go back and investigate. But when virtually every federal agency looks at the evidence and decides that there’s not enough data to support the idea that cellphones cause cancer, we should listen to them over IARC. IARC isn’t making judgments based on what’s actually posing a threat to your health. The NCI and the NIH are, and they’ve spoken loud and clear: cellphones don’t give you cancer.

So go ahead and use your phone as much as you want. Duct tape the thing to your head and have an eight hour call every single day. All the research says you’ll be fine. Those Italians may know their coffee, but their jurors clearly don’t know their basic biology.