This article was originally featured in Undark.

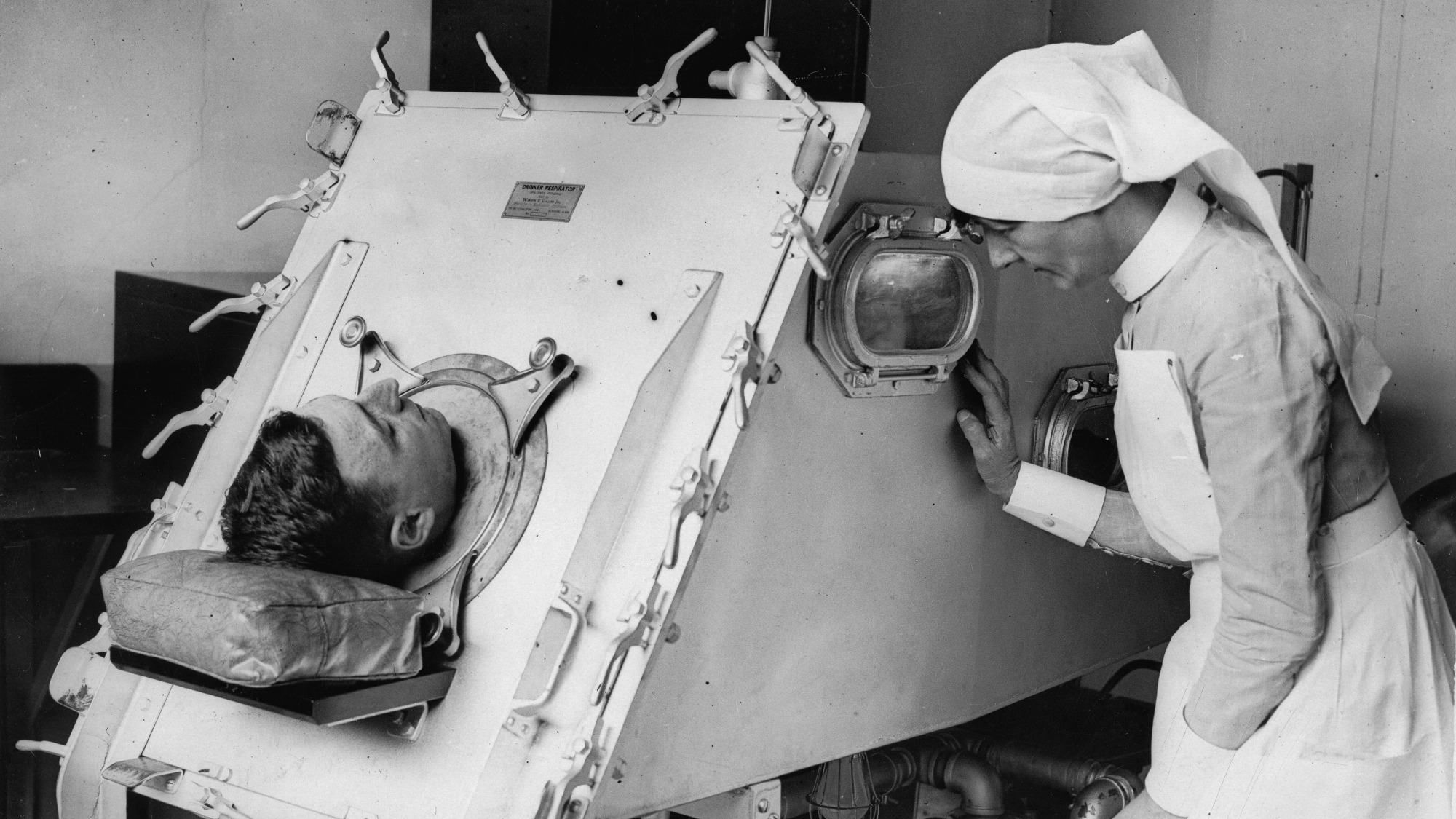

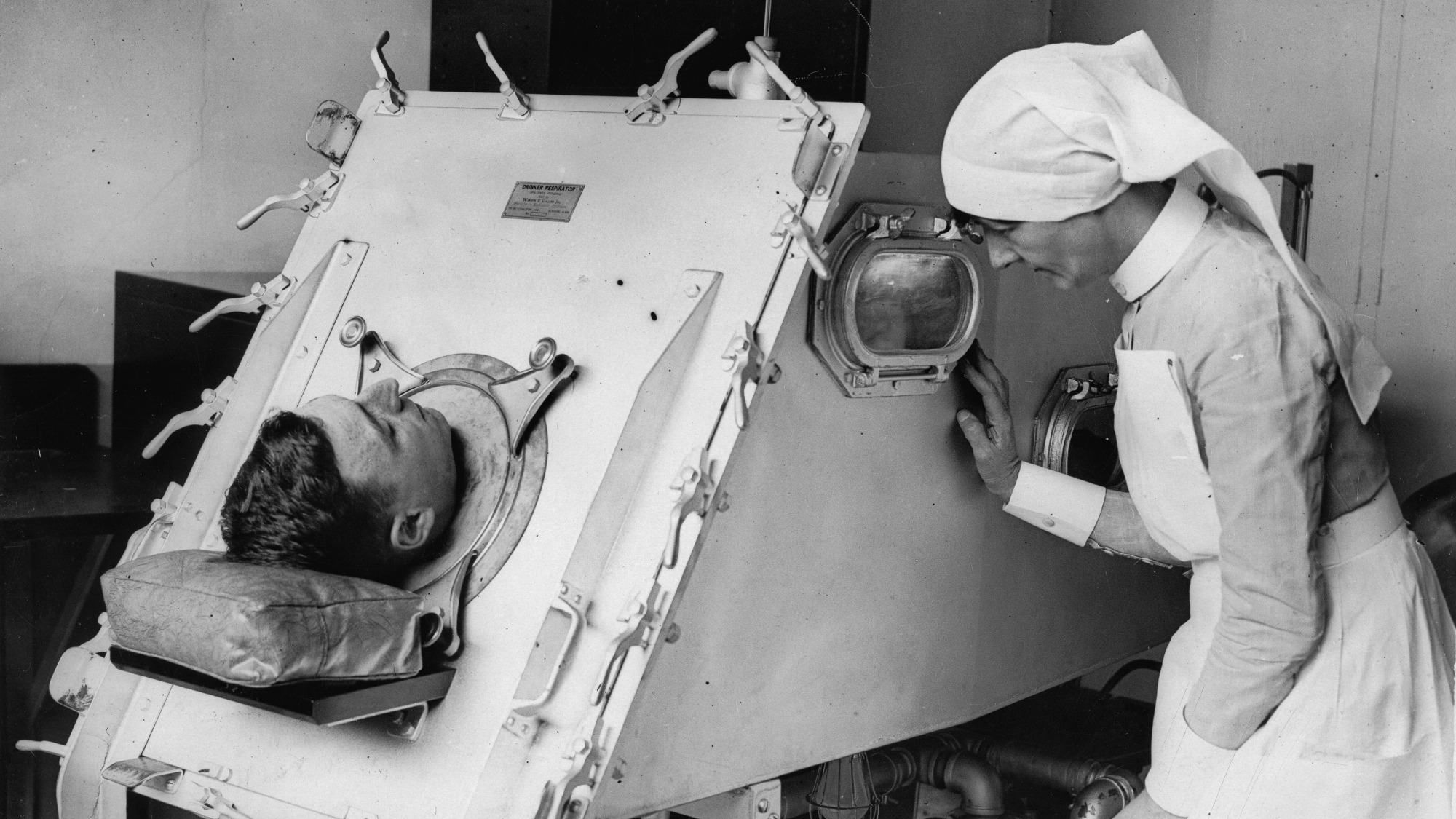

Brad Fuller was a toddler when he contracted polio in 1952 and was sent to a hospital miles from his northeast Pennsylvania home. He stayed there for nine months, enduring long stints in an iron lung, a large metallic ventilator that helped him breathe. Fuller’s parents were allowed only rare visits. His earliest memory is of a nurse holding him in a mineral pool, instructing him to kick his legs.

That year marked the epidemic’s peak, when roughly 58,000 American children and adults developed polio and 3,000 of them died. In this respect, Fuller was lucky. The disease spared him, leaving only a weakened left leg and right arm. He was able to play tennis and football and train as a clinical psychologist. He built a career leading non-profits while teaching part time at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia. Despite his childhood ordeal, Fuller said, he felt invincible.

Then, in his 40s, a new doctor offered to treat his post-polio. Fuller was taken aback. It was the first time he’d heard the term. But the symptoms, like increased muscle weakness and poor balance, had been creeping up. At one point, he’d fallen and injured his knee. He now wears a full leg-brace and because he falls so often, he has taught himself to land easily. “I think if I was a typical person” — a person without a background in mental health — “I would have immediately gone into denial,” he said.

Scientists believe that the poliovirus has been around for thousands of years, but it did not cause epidemics until the late 1800s, when countries like the United States and the United Kingdom began to experience waves of increasing severity. By the 1940s and early 50s, the polio terror was killing or paralyzing more than a half million people globally each year. To treat the overwhelming number of sick people, hospitals created the first intensive care units. Many of those ICU patients were children and young adults.

Then came a pair of highly effective vaccines, the first of which was licensed in 1955. Case rates plummeted within a matter of years, and the virus was soon eradicated from entire countries. The vaccines are widely viewed as a triumph of public health. “My mother would have given anything to have a vaccine” for her children, recalls Fuller. But for those who had already been infected and survived, there was a downside. Polio “supposedly disappeared,” Fuller said. “That means research stopped.”

This history is bittersweet for patients who now struggle with post-polio syndrome, or PPS, which affects 25 to 40 percent of survivors. As adults, these individuals face an array of new symptoms stemming from their initial infection — everything from pain and renewed muscle weakness to fatigue to problems speaking and swallowing. PPS affects up to 300,000 people in the U.S., and globally the figure could be as high as 15 to 20 million people, according to some estimates. Most polio survivors in developed countries are 65 and older, said Marny Eulberg, a physician with PPS who ran one of the first dedicated clinics in the U.S. Survivors in the developing world are often younger.

Fuller was fortunate in another respect. His physician recognized the signs of PPS. Many patients struggle for years to find an explanation for their various symptoms, only to find out, once they receive a diagnosis, that there are no approved treatments and few specialists who can help them manage their condition. The exact cause of PPS remains unknown, and it has confounded researchers seeking a cure. Further research could elucidate polio’s long-term effects and stall patients’ physical decline, say the handful of scientists still studying the condition, but funding is scarce.

“The sentiment in all the funding bodies is polio has disappeared. So are we going to put money in it?” said Frans Nollet, a leading figure in European post-polio research who heads a specialty clinic at Amsterdam University Medical Centers. “It’s difficult,” he continued. “People think the disease has vanished, but the patients are still here.”

Like polio itself, post-polio syndrome is thought to have been around since ancient times. But it didn’t capture the medical world’s attention until the generation of young polio patients from the 1940s and 50s reached adulthood.

That’s when Marilyn Fletcher, a physician and polio survivor, approached the National Institutes of Health for help. In 1982, after repeated phone calls and visits to the federal agency, Fletcher landed a meeting with the neurologist Marinos Dalakas. At least 20 polio survivors in and around Washington D.C. were experiencing new symptoms, she told him. These individuals had even coined a new term, “post-polio syndrome,” to describe their condition. Thousands of people across the U.S. could have similar symptoms, Fletcher maintained. Those in D.C. were frustrated that the medical community was ignoring them.

Dalakas was initially skeptical and took no action. But a month later, he received a call to meet Fletcher at the Surgeon General’s office. Everett C. Coop, newly appointed to the position, “expressed his concern about the emerging phenomenon of PPS as described by Dr. Fletcher,” wrote Dalakas in a 1995 paper. Soon thereafter, Dalakas headed up a first-of-its-kind survey to learn more.

The survey was sent to 2,800 individuals with medical records indicating a polio-related disability. At least 2,500 people replied, often sending letters and personal photographs along with their questionnaires. “Many of the responses contained details which were highly emotional and stimulating,” Dalakas recalled in an email to Undark. For example, a 50-year-old man who’d contracted polio at 19 was struggling to drive or even dress himself. The devastating toll of PPS quickly became clear to Dalakas.

But how to define this new condition was less obvious. Collectively, the study participants reported a wide variety of ailments, with the onset of new symptoms occurring years to decades after the initial infection, often when survivors were in their 30s, 40s, or 50s. Because of this heterogeneity, experts disagree even today about what constitutes PPS. An official diagnosis requires a 15- or 20-year period of stability without new weakness or impaired movement.

Yet Frances Quinn, who contracted polio as a 1-year-old, said her symptoms have never truly been stable. At age 14, she felt growing weakness in her upper right arm and in her thumb. Her health care provider, she said, attributed these changes to adolescence and her accompanying loss of baby fat. “There’s a lot of stuff said about PPS that’s not really based on good science,” said Quinn, who worked as a physicist in the U.K. government for most of her life. “PPS is diagnosed when the patient decides that something is wrong and also finds someone who will listen to them.”

Katharina Stibrant Sunnerhagen, a professor of rehabilitation medicine at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, raised similar objections. “My problem is that, for instance, if you had polio as a 1-year-old, when is your condition steady?” Childhood and adolescence encompass periods of rapid physical growth and development. Strictly speaking, an individual who survives polio as a baby must wait until the completion of puberty before their 15- to 20-year period of stability can even commence.

PPS was formally redefined by the World Health Organization in February of 2022, when it updated its International Classification of Diseases. The WHO now calls PPS “post-polio progressive muscular atrophy.” Critics have argued that the redefinition does not reflect the spectrum of symptoms patients may endure, increasing the risks that patients will receive the wrong sort of care. Why change it at all? asked Quinn. “It took 40 years of work to get PPS recognized and creating more names only adds to confusion.” Some sufferers also worry that disability payments could be affected although, for now, practitioners in the U.S. and U.K. still refer to the older classification.

Government recognition of PPS as a disability has been important because symptoms often appear in mid-life, making it difficult for some patients to sustain their careers. Carol Ferguson, a polio survivor and mother, used to work at a Pennsylvania bed-and-breakfast but was obliged to quit when she could no longer stand all day. “My physicians made it very clear that that part of my life was over,” she said.

Some post-polio patients originally had mild symptoms. Others needed leg braces, calipers, or an iron lung. For the latter group, the reemergence of symptoms can feel like a deal gone sour. Eulberg contracted polio in 1950, when she was four. She recalls being promised that if she just worked hard enough, she would be able to walk without a leg brace. In junior high that promise was fulfilled. But decades later, her muscles started to weaken and she realized she needed a brace again. It “felt like a failure,” she told a Medscape reporter in 2020.

There are also unexpected risks. In rare instances, anesthesia can prove fatal for those with PPS, who may need as little as half the dose of typical adults because of an increased sensitivity to sedatives and other drugs. They may have difficulty breathing or swallowing, or be slow to rouse after treatment, possibly having the same vulnerabilities as other patients with neuromuscular disorders. John MacFarlane, a campaigner and former president of the European Polio Union, had given a talk about PPS to the British Medical Association. While leaving the conference building, his wheelchair tipped into a pothole and toppled over. He later needed an operation to pin and plate his arm. He told Undark that it took him 14 hours to wake up after surgery.

For many years, Ferguson, the former B&B worker, didn’t even realize that she’d been infected with the poliovirus. When she came down with a fever at the age of two, just a year before vaccines became available, she recalls, her parents assumed it was a “summer flu.” Ferguson developed a drop foot at age 11, and a doctor suggested polio as the possible cause. But Ferguson’s mother was dubious, and the disease was not mentioned again. Feelings of self-blame may have contributed to the situation, said Ferguson. At the time, many parents believed that if they simply kept a clean house, their children would not fall ill.

Ferguson grew up a clumsy kid who stumbled a lot. As an adult, she fell while ice skating and had to undergo a minor surgery. She woke up three days later in intensive care. The anesthesiologist, she recalls, probed for details that might explain why it had taken so long for her to wake. When she mentioned her summer flu, he warned, “Don’t ever leave that out of your medical history again.” The physician suspected that the flu had actually been polio and that Ferguson was experiencing the condition’s lingering effects. But he did not provide an official diagnosis of PPS.

For that, patients must undergo a battery of blood tests, scans, and X-rays to rule out other health conditions. Ferguson recalls starting along this path and encountering several doctors who thought she had multiple sclerosis; another was sure she had a brain tumor (“That’s the kind of thing that really messes with your head,” she said). When those conditions were eventually ruled out, a neurologist at the University of Pennsylvania conducted a diagnostic test called an EMG, which evaluates the function of motor neurons. Ferguson recalls lying in bed with needles in her leg, her husband holding her hand to ease her pain as the test recorded electrical activity in her muscles. She told Undark that partway through, the physician called his students to the room to show them what a case of “old polio” looked like.

For Ferguson, it was a moving moment. Her journey to diagnosis had come to an end. “We finally had it,” she said. “Everything else had been ruled out.”

For help managing her symptoms, which included deepening fatigue and a weak leg, Ferguson went to a polio clinic in Englewood, New Jersey. Like other clinics, this one provided access to an array of specialists, including rehabilitative physicians, occupational therapists, physical therapists, nutritionists, and orthotists — specialists who make braces and splints. Ferguson had been walking 10,000 steps a day, trying to keep healthy. At the clinic, she learned that she was over-using frayed muscles. This kind of insight, and the clinic’s care more broadly, are what ultimately “saved me,” Ferguson said.

Despite their benefits, polio clinics have been shutting down, said Carol Vandenakker-Albanese, a professor of health sciences who runs a clinic at UC Davis. Many physicians who once specialized in treating the disease have retired, she said, estimating that only about two dozen polio specialists currently practice in the U.S. With most survivors now in their 60s and 70s, few young clinicians want to take up the mantle.

Four specialists told Undark that there is a concerning lack of knowledge among their medical colleagues about PPS. Despite a steady trickle of published studies since the 1980s, many doctors are too busy to keep up with the science and simply “don’t believe in PPS,” said Richard Bruno, who trained in psychophysiology and led the Englewood clinic where Ferguson was treated. In Sweden, a patient told Sunnerhagen that when she asked her family physician if ankle pain could stem from childhood polio, the doctor replied, “Polio is a vaccine.”

Ferguson now volunteers with a Pennsylvania-based support group that she helped establish, which offers a list of recommended specialists and publishes newsletters and personal stories. Support groups exist in other states too, providing patients with an opportunity to swap details about symptoms and possible treatments and share tips for educating their doctors and advocating for themselves. In Germany, a doctor with PPS has argued that patients could benefit from medical cannabis, and he has developed a protocol to help patients with their symptoms. But, he said, insurers and other physicians are reluctant to accept the therapy.

Brad Fuller, the survivor whose first memory is of being in a mineral pool, would like to see the U.S. government offer more support to PPS patients. Some of them need braces or wheelchairs in order to continue living productive lives, but such mobility aids, he said, are “outrageously expensive.”

“Basically,” said Eulberg, who councils patients at the clinic she founded in Wheat Ridge, Colorado, “we’re telling polio survivors, ‘Yes, it would be wonderful if every health care provider you encountered knew a lot about polio, but that ain’t going to happen. You’re going to have to be your own advocate.’”

In 2001, Antonio Toniolo, a microbiologist and physician, experienced a serious car accident. To recover from his injuries, he spent two years visiting a rehabilitation clinic, where he encountered middle-aged polio survivors who were seeking help for their muscle weakness. At the time, Toniolo was working at the University of Insubria Medical School in Italy. The survivors, he recalls, started referring to him as “Doctor” and asking, “What do you know about polio?”

Then, as now, the cause of PPS was not well understood. Researchers know that the initial infection kills some of the body’s motor neurons, the cells that facilitate communication between muscles and the brain. Over time, some of these neurons regrow dramatically, reaching 7 or 8 times normal size, but they are unable to maintain themselves and eventually start to die off. But why this die-off happens, and why some patients are more affected than others, remain a mystery.

Throughout the 1980s and 90s, researchers focused on defining PPS and on trying to understand its underlying causes. After studying that literature, Toniolo began to wonder if the poliovirus might still be present in the blood of survivors — something earlier research had suggested — and causing their new symptoms. In 2013, he gathered blood and spinal fluid from 100 post-polio patients and compared the samples with those from a control group of about 50 survivors who weren’t experiencing PPS. He found traces of poliovirus in samples of about two-thirds of the PPS patients, compared with very few of the control group’s samples. The still-circulating virus, he posited, could cause inflammation or even cell death in those patients. This would mean the condition might respond to antiviral drugs.

Toniolo shared this preliminary data at a couple of PPS-related events and in a mid-study report published in 2015. But the research was never finalized or published in a scientific journal. “This was expensive research that needed funds and competent people,” he wrote to Undark in an email. “Thus, due to lack of funds and my retirement at the end of 2018, the work has not been completed.”

As of yet, nobody has tested whether PPS might respond to antivirals. A major multi-center study led by Dalakas is focusing on whether certain proteins in the blood of healthy donors could help neutralize proteins called cytokines that scientists have detected in the blood and spinal fluids of some PPS patients. Researchers hope that the therapy, called IVIG, will calm the cytokines and stabilize the immune system, thereby improving patients’ quality of life.

The treatment has been trialed in Sweden without conclusive results and was available for a while in some countries, Nollet from the Amsterdam University Medical Centers said, but because it was considered not sufficiently proven, insurers were reluctant to cover it. Whatever the outcome of this study — which is sponsored by a Spanish company, Grifols — it will be helpful for patients to know whether it works or not, said Nollet, whose clinic is among those taking part.

The Swedish government is rearranging care of rare diseases so that polio survivors will be treated at expert centers, a decision driven by recent events: Last summer, health officials reported that the poliovirus had paralyzed an unvaccinated man living in an under-vaccinated community in New York. It was the first U.S. case in years. As of early October, the virus still appeared to be spreading in several under-vaccinated parts of the state. In 2022, for the first time in decades, poliovirus was also detected in Israel, Malawi, Mozambique, and the U.K., alarming public health officials and spurring calls for vaccination campaigns.

Observing the cases in New York helped the Swedish government understand that a polio outbreak “is something that can actually happen again, even here,” said Sunnerhagen, whose own PPS research is part of an application for special status at her university hospital. Her clinic serves about a thousand post-polio patients, a largely Swedish cohort alongside a younger group of individuals who immigrated to Sweden from countries where the disease was never eradicated. “We need to spread the knowledge,” she said, to draw attention to the fact that polio patients are still present in society. Sunnerhagen doesn’t expect all physicians to be experts in the condition but she hopes that they will at least know to make the referral.

For now, patients are still driving much of their medical care.

Ferguson said she understands why a physician might be stumped by a multi-symptom disease triggered by a long-ago infection. “But to totally deny that this exists is heartbreaking,” she said. “I’m a living example that a very mild or unapparent case of a virus can leave lifelong damage.”

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.