The Karelia regions of Finland and Russia are remarkably similar. They have unique architecture, they share a common heritage and genes, and speak similar dialects. But if you live on the Finnish side, you’ll have around ten times as many neighbors with celiac disease.

And no, it’s not because Finns eat more bread. If anything, Russians eat more gluten than do their Scandinavian neighbors, so you can stop right now with the “it’s because we eat such refined wheat products!” argument. That’s not the whole story. It’s not yet clear exactly what’s causing this massive divide between two very similar populations. Even without an answer, though, it is a useful paradigm.

See, we know that almost everyone with celiac disease has one of two genetic abnormalities. That seems to suggest that celiac is mostly a hereditary problem, not an environmental one. But look at Karelia—two groups of people with nearly identical genetics, yet vastly different patterns in celiac prevalence. Really, the main difference between Finnish Karelians and their Russian counterparts is their lifestyle. And it’s not just Karelians. A significant fraction of people have the same genetic abnormalities as those who develop celiac, but only about one percent of the population actually gets the disease. About 15 percent of all monozygotic twins with the celiac markers don’t both develop it. And all this means that celiac isn’t only a genetic problem—it’s about your environment as well.

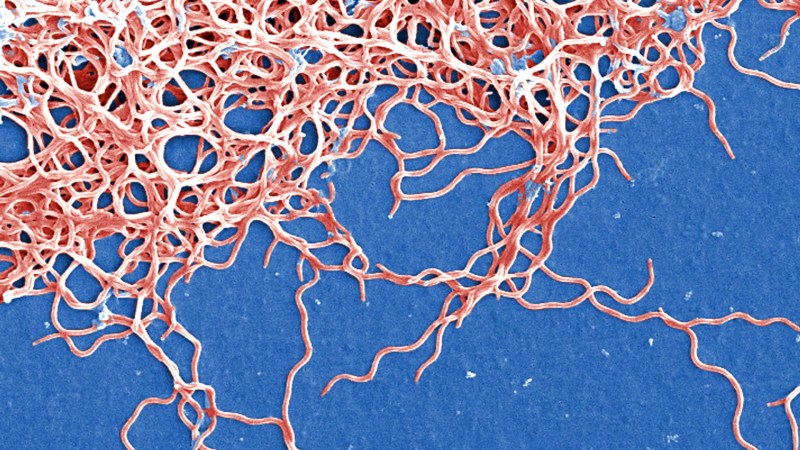

There seem to be a lot of factors that influence your likelihood of getting celiac. One of the more popular theories, though, is infection. Infections obviously have short-term effects on your immune system, but some can have more lasting impacts. Take reoviruses. You’ve probably never heard that term before, because unlike a rhinovirus (the common cold) or rotavirus (diarrheal problems), they don’t make you sick. Or rather, they don’t make you conspicuously sick. Reoviruses mostly cause subclinical infections, which means your body is actively fighting them off but you don’t develop symptoms that clue you in. That makes reoviruses almost entirely harmless—unless you have the genetic abnormalities that lead to celiac disease.

Researchers at the University of Chicago, along with several other leading institutions, suspected that reoviruses could permanently change the immune system such that you would be more likely to develop celiac disease, assuming that you already had the genetic markers. And they were right. They published their results in Science on Thursday, showing how a reovirus could impact the gut long after it’s left your body.

Reoviruses + gluten + genetic abnormalities = celiac disease?

“The gut is a huge entry for bacteria and viruses,” explains gastroenterologist and celiac expert Bana Jabri, who is the lead researcher on the paper. Since the intestines are constantly seeing new bacteria and viruses, we’ve developed an immune system that can identify which incoming proteins are from invaders and which are simply foodstuff. “It’s almost as if we have a system that favors entry at certain sites. It’s designed so that the enemy comes in through a certain door, because beneath that there’s an army of immune cells waiting to attack.”

That system works well almost all of the time. It even works well if you have one of those two genetic abnormalities. The mutations are actually called HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8, which is an abbreviation for a part of your immune system that identifies self from non-self called the human leukocyte antigen (HLA). In people with DQ2 or DQ8, that identifying function can get confused. And if you also happen to have, say, a reovirus infection at the same time as you’re eating a gluten-containing food, your immune system might get mixed up. Some reoviruses cause an inflammatory reaction at a separate location from where the immune system encounters gluten.

But some don’t. Some reoviruses cause a flurry of activity right where the body is identifying gluten, and if you have one of the HLA abnormalities it’s easier for your immune system to conflate the two reactions. It thinks that the inflammation it’s experiencing is from gluten, not from the reovirus, so it starts producing cells specifically designed to attack gluten.

This is essentially what celiac disease (and really every autoimmune disorder) is: the body getting confused about what should and should not be attacked.

Jabri and her team did this work primarily in mice, since they could genetically engineer them to have human-like celiac mutations and use a human reovirus to experiment. Give the mice these genetic abnormalities, expose them to gluten and the virus, then watch as they lose the ability to digest gluten. They were essentially watching the process of developing celiac in miniature.

They didn’t stop at mice, though. They went on to look at whether celiac patients had actually had reovirus infections. Surprise, surprise—they had. Not every person had indicators that they’d seen a reovirus before, but a subset had blaring signs in the form of lots and lots of antibodies against the virus. Those patients also had a kind of immune signature—certain changes that the reovirus had induced—that were identical to what the researchers saw in mice. That’s no coincidence.

Here’s why all this matters

This probably won’t help you if you already have celiac. It could help future generations, though. “This is an exciting study to my mind, because it provides some mechanistic explanation for the epidemiological studies,” says gastroenterologist and celiac specialist Peter Green at Columbia University, who was not involved in the study. “Once we know the mechanism, we could start to consider possible therapies.”

People who inherit HLA-DQ2 or -DQ8 could be vaccinated against celiac-inducing reoviruses, making them less likely to develop the full-blown disease. Green points out that epidemiological studies already suggest that would work. Vaccines against rotavirus, which have also been linked to celiac, seem to protect against the disease.

One infection might not be sufficient to trigger celiac, but over time various factors add up until it’s bad enough to produce symptoms. Or not. We know that celiac is under-recognized and under-diagnosed, especially in the U.S.—and there are plenty of patients who have no symptoms and yet still end up with intestinal damage.

And as always in the world of science, it’s not as simple as one factor. Green notes that taking antibiotics and being born via c-section both increase the risk of getting celiac, which suggests the microbiome plays some role in things. And there’s a gradation in how common it is across the U.S., such that people in the northern states have higher risk. That could mean vitamin D has an influence.

The point is, there’s a lot left to learn about celiac, and the more we learn about what causes it the more therapies we can develop. That might only matter to one percent of the population, but just try telling someone with celiac that they can eat a chocolate croissant again. Or have a slice of pizza. A group of Australian celiac patients who got hookworms as an experimental therapy chose to keep the parasites in their guts rather than go back to avoiding gluten. And a vaccine beats intestinal worms any day.

![A Field Guide To Caffeinating Yourself Into Oblivion [Infographic]](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/7UNYGK52H4FZ5CYMPQMJZQVKAY.jpg?w=525)

![The Haunting Math Of America’s War On Drugs [Infographic]](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/FT6DSIS3UDAXH7NVL7SKRPYDAY.jpg?w=525)