We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

Hang time has always been a problem on the moon. The Apollo program landed a dozen men there from 1969 to 1972, but they spent a total of only three days and six hours actually walking the surface. That’s because they couldn’t stray from their lunar lander and its life support. To help future moon men and moon women extend their stays and their range, and to make the most of their time exploring, aerospace engineers at MIT have now designed lightweight, packable, inflatable habitats.

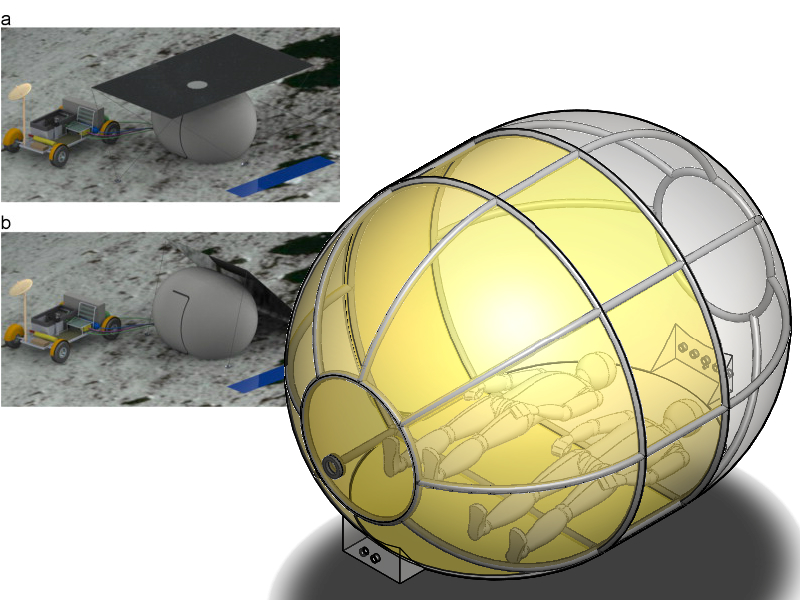

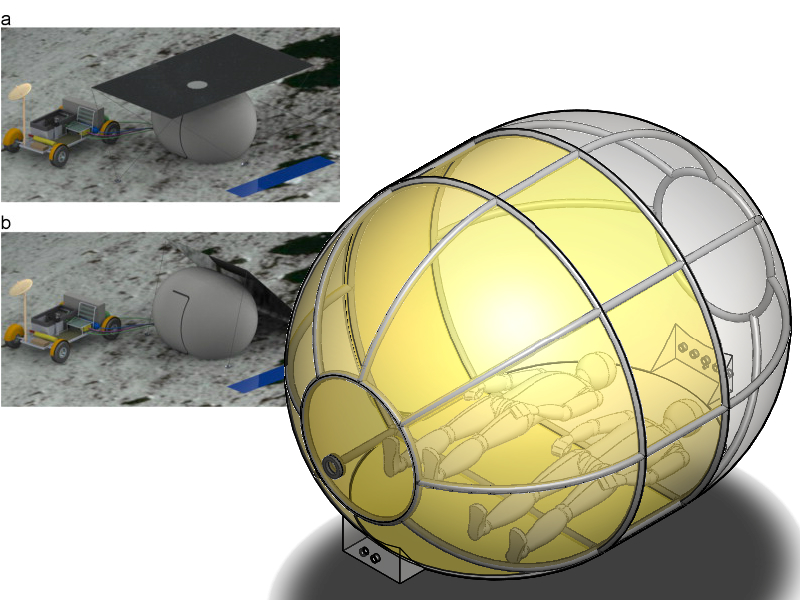

The mobile overnight habitat, designed to fit aboard a no-frills lunar rover, is made up of an inflatable pod that sleeps two; a reflective shield to prevent the sun’s rays from roasting explorers; life support systems on the rover that will supply oxygen, water and food, maintain the habitat’s temperature, scrub out carbon dioxide, and remove excess humidity; and a flexible roll-out solar array to supply the shelter’s power and recharge the rover’s batteries. When packed, the entire system, would take up roughly half as much space as an average refrigerator, says Samuel Schreiner, one of the MIT engineers.

Astronauts would set up the shelter using inflatable tubes made of the same silicone-coated fabric that the Mars Pathfinder and Mars Exploration Rovers used in their landing bags. These pressurized tubes would serve as support ribs, giving the habitat a pill-like shape, and providing roughly 425 cubic feet of habitable space. Once the astronauts enter the pod, and close the airlock, the life support systems on the rover will kick in and fill the habitat with oxygen via umbilical cables.

Moon dust, which collects on the astronaut’s suits, poses a problem. The dust is electrostatically charged and sticks to everything, the way a rubbed balloon attracts lint. It is also dangerous, each grain similar to a shard of glass. “On Apollo 17, Harrison Schmitt reported feeling congested and complained of hay fever symptoms from inhaling lunar dust,” Schreiner says. “Lunar dust can also cause skin and eye irritation and corrosion and, when inhaled, can possibly cause lower-airway issues.” So Schreiner and company created a flexible divider inside the pod that can be moved to cordon off the area where astronauts remove their suits from where they sleep. He also believes astronauts could use magnetic wands to pull off dust and use air filters to keep the habitat breathable. “This is still an area of open research that NASA is looking into,” he says, but not part of his project.

The proposed habitat is more compact than anything engineers have previously dreamed up, making it a realistic fit for future missions. Consider the 1960s Lunar Stay Time Extension Module that Goodyear designed. Meant to support two astronauts for eight days, it weighed 1,276 pounds, nearly as much as a small car. The MIT habitat, by contrast, supports two people for a single overnight mission and weighs in at 273 pounds.. Such an overnight shelter could double the distance reachable from a permanent, as-yet-to-be-built moon base. This could, for instance, help explorers investigate a variety of sites at the 60-mile-wide Copernicus impact crater, one of the most prominent craters on the moon. Probing Copernicus from its floor to its central peaks could yield key insights on the history and evolution of the moon, Schreiner says.

Deflating the habitat to stow it back on the rover should be easy, too because “the lunar vacuum will make it relatively easy to evacuate all of the gas within,” says Schreiner. He and his team detailed their work online in the journal Acta Astronautica.

Schreiner cautions, however, that his team’s concept is still in the early stages and as such designs mature “the mass and volume of the system often increase by about 20 to 30 percent, but that still puts our design in a reasonable range,” he says.

The engineers imagine that their inflatable, packable habitat will first be used for overnight trips when the lunar lander is still what astronauts call home. But it could also be used after larger permanent moon bases are built,. Schreiner also sees another function: as a quickly deployable emergency shelter if a spacesuit fails. And in case the astronauts have trouble setting up the habitat and cannot enter it, the engineers say they can hook their suits up to the habitat’s life support systems on the rover and drive back to base.

Of course, a moon visit might be a long way off. NASA cancelled its deep-space Constellation program—which might have put astronauts on the moon—five years ago, and has no plans to revive it. Still, Schreiner believes, “humanity will, at some point, return to the moon. At some point in the future, the moon will present an intriguing exploration destination, both for its proximity to the Earth and also for the interesting science and exploration that has yet to be done. The moon is by no means a closed case, and there remain many compelling reasons for humanity to return.”