Helicopters aren’t easy to fly. Consider this: a pilot operating a helicopter in hover mode, without an autopilot, literally cannot take their hands, or feet, off the controls, or it could quickly crash.

Of course, an autopilot can help in situations like that, but helicopter-maker Sikorsky is developing a system that goes well beyond that, adding a layer of autonomy to a helicopter flight system. Making a helicopter easier to operate—or totally autonomous—would have obvious benefits: one of them is that a military pilot, in a complex and dangerous setting, could focus their attention on big-picture mission planning as opposed to the nuts-and-bolts of actually keeping the bird in the air.

That’s one of the reasons that Sikorsky has been working on a helicopter pilot-augmentation system they call Matrix, and while they’ve already tested it on a helicopter model called the S-76, the company has something else in store: a Black Hawk—a helicopter long used by the Army—equipped with Matrix that, while it hasn’t flown yet, should one day be able to fly itself.

The conceit behind the automation system “is to augment the human on board,” says Mark Ward, a chief pilot at Sikorsky. The system can remove what he calls “the mundane task of flying” from the pilot, so that they can focus on other complex tasks at the same time they’re motoring around. It can provide various levels of automation, and even handle a flight on its own.

“I can tell the aircraft, ‘I’m here at position A, take me to position B, and land,'” says Ward. It’s advanced enough that a reporter for Wired flew the helicopter with very little training, calling its controls “as intuitive as any videogame.”

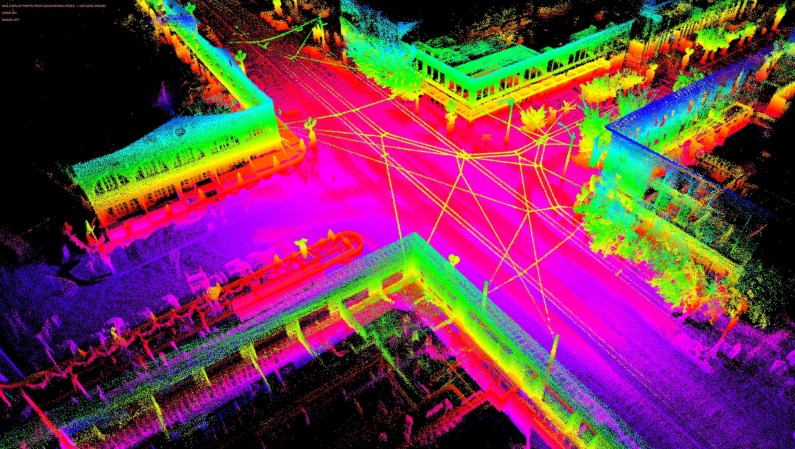

And unlike an autopilot, this automation system has a sense of what’s going on around the helicopter, thanks to multiple perception sensors—which is also how a self-driving car knows what’s happening in its immediate environment.

A Black Hawk down to fly solo

For the Black Hawk, the idea is that the automation system could offer various ways of helping out the two-person flight crew. In one scenario for a complicated mission, the autonomy systems helps out both crew members onboard. Or, in a more straightforward scenario, you “flip the switch to one crew,” says Chris Van Buiten, vice president for innovation at Sikorsky, meaning that one pilot, plus the Matrix system, flies the bird, while the other stays on the ground.

Or zero people could fly it. The vision is that if an assignment “is super dull or super dangerous, put it on zero crew, and have the Black Hawk fly the mission itself,” says Van Buiten. Before those pilotless Hawks carry troops, though, they would start by just ferrying cargo. “We’re going to have to earn the right where there’s no [flight] crew on board, and we’re picking up people.” (The Black Hawk with the autonomous system has not yet flown, but it could take to the skies this year.)

And all of this raises a weird possibility: just like a driverless car can act as an urban taxi, picking people up and dropping them off, could the Army one day send a Black Hawk with no one on board to pick up pilots and crew at another location?

What about pilot skills?

“Pilots are becoming more like mission planners, or aircraft commanders,” says Richard Anderson, a professor of aerospace engineering at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. When the situation is simple, then the act of physically flying the aircraft happens easily for the pilot, cognitively-speaking.

But when things get tricky, the “brainpower required to keep the aircraft flying and safe goes way up,” Anderson says. But in those situations, if an autonomy system can take the flying task away from the pilot, the human can determine something bigger-picture: “where the helicopter goes, not how to get the helicopter physically there,” he says.

Anderson, a licensed airplane and helicopter pilot, knows how demanding flying a helicopter with no autopilot or automation can be: In an extreme case, he says, a pilot flying an old-school helicopter by themselves would have to land just to have a hand free to adjust the radio frequency.

In other words, autonomy systems can certainly help out, especially in complex situations. Or they could help power a future in which helicopter-like flying taxis help people get around cities, as Wired pointed out when they tried Sikorsky’s Matrix tech. In that scenario, the people operating the flying taxis may not need as much training as a full-blown pilot.

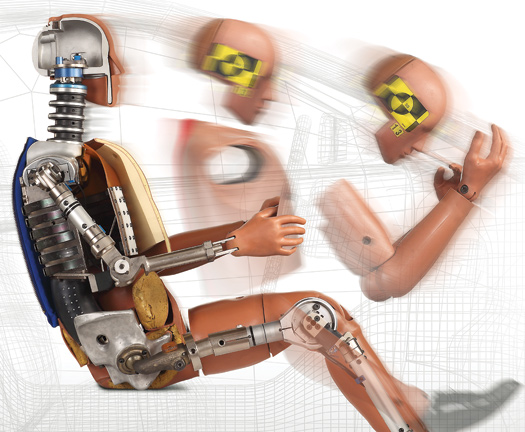

But here’s the catch: if a pilot with less training—someone not trained to handle a complicated situation—is flying a helicopter with an automation system, that system has to be 100% reliable. In other words, it can’t glitch and hand the pilot a situation that they’re not trained for. In a future with more aviation autonomy, “the answer is eventually going to have to be—it can’t fail to a worse situation than what you’re used to flying,” Anderson says.

“At some point, the world’s just going to have to say, ‘pilots aren’t going to know how to do the stick and rudder,’” he adds, “and we’re going to have to make that jump—and I don’t know how that all plays out.”