According to plan, the Federal Aviation Administration will let drones into American skies by 2020. A report released last week by the Office of the Inspector General for the Department of Transportation is very, very skeptical that all is going according to plan. Titled, subtly, “FAA Faces Significant Barriers To Safely Integrate Unmanned Aircraft Systems Into the National Airspace System,” the report outlines significant challenges to a future filled with flying robots.

As outlined in the FAA’s roadmap, the first stage to integrating unmanned aircraft with manned flying machines in the same skies is establishing test sites. Selected in December, some of the test sites, like the one in Grand Forks, North Dakota, are already up and running. But moving from small test sites to a future of safely integrated skies may never happen.

The report, authored by Matthew E. Hampton, Assistant Inspector General for Aviation Audits, lays out three major failings of the FAA:

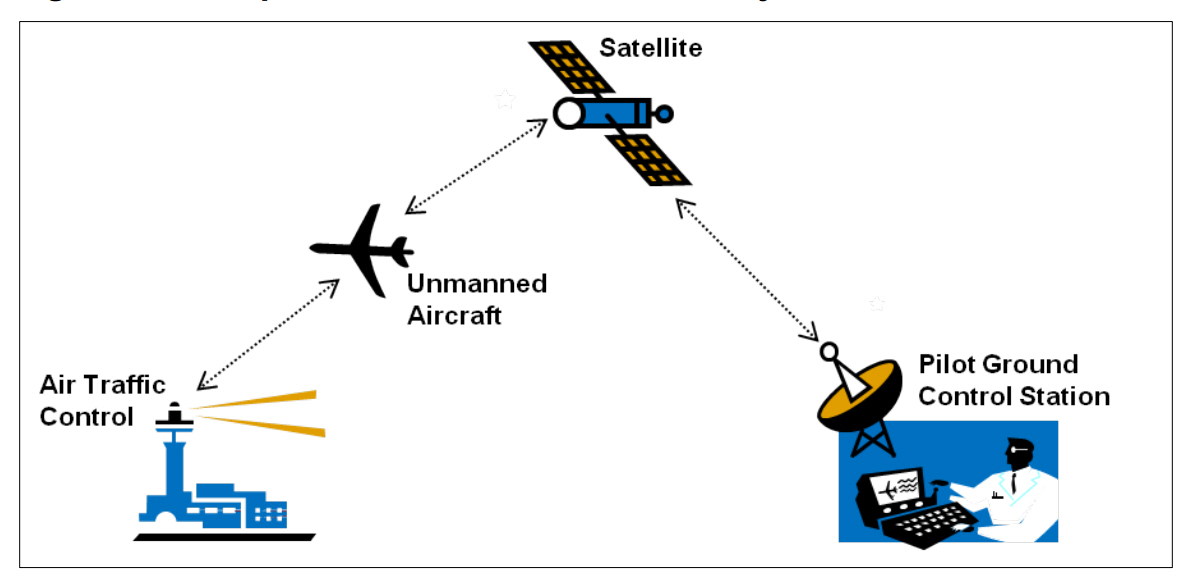

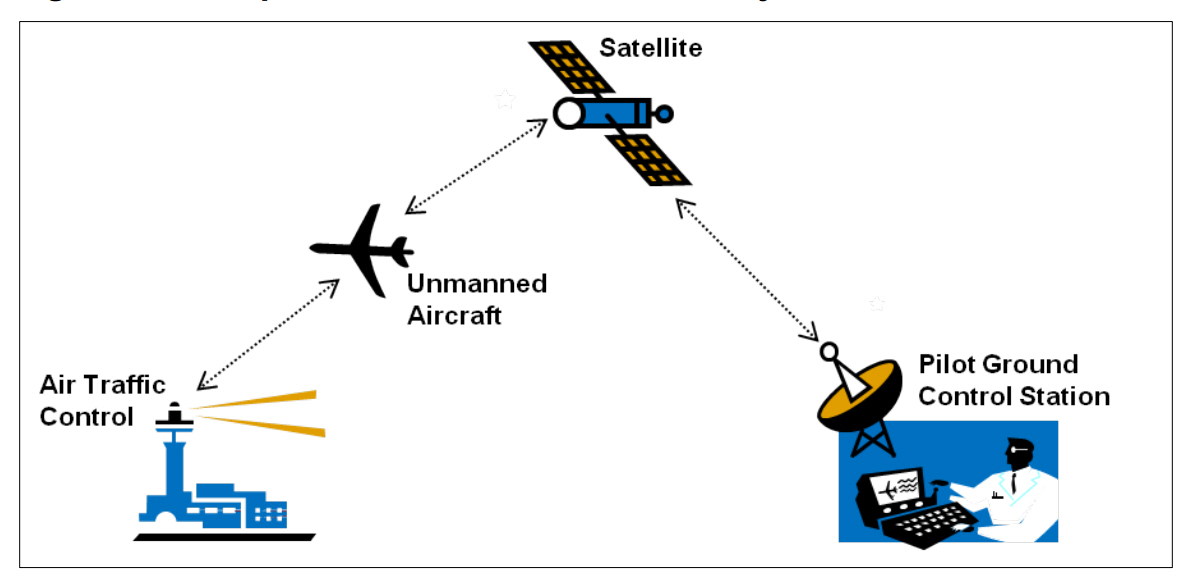

- First, following many years of working with industry, FAA has not reached consensus on standards for technology that would enable UAS to detect and avoid other aircraft and ensure reliable data links between ground stations and the unmanned aircraft they control.

- Second, FAA has not established a regulatory framework for UAS integration, such as aircraft certification requirements, standard air traffic procedures for safely managing UAS with manned aircraft, or an adequate controller training program for managing UAS.

- Third, FAA is not effectively collecting and analyzing UAS safety data to identify risks. This is because FAA has not developed procedures for ensuring that all UAS safety incidents are reported and tracked or a process for sharing UAS safety data with the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), the largest user of UAS. Finally, FAA is not effectively managing its oversight of UAS operations. Although FAA established a UAS Integration Office, it has not clarified lines of reporting or established clear guidance for UAS regional inspectors on authorizing and overseeing UAS operations. Until FAA addresses these barriers, UAS integration will continue to move at a slow pace, and safety risks will remain. [emphasis added]

Nested within these challenges are further challenges still. The FAA wants two technologies to make drones safer. One is “sense and avoid,” where the aircraft without onboard pilots can detect and move away from other aircraft, the way an onboard pilot could see something and steer clear. This technology isn’t ready yet, though researchers are working on it. The other technology the FAA wants to be ready before integration is secure link technology, which will keep the pilot on the ground in contact with the drone at all times. Even the military struggles with this one. In 2010, a U.S. Navy Fire Scout drone lost link with its pilot and then flew into the highly restricted airspace over Washington, DC.

Besides technical challenges, there are legal issues. The FAA is a regulatory agency; its rules are designed to keep the sky safe by making sure everyone flying is on the same page. Yet their approach to drones, and especially commercial drone uses, is presently haphazard, as it occurs on a case-by-case basis. In addition, drones are grouped into two categories: under 55 pounds, and over 55 pounds, which confuses model airplanes and small drones. Here too the Inspector General finds fault.

Further failings are found in data sharing, air traffic controller training, progress towards goals stated in the FAA’s roadmap, and integrating the concerns of the many groups that want to use drones. It’s a bleak report, and it ends with 11 suggestions for improvement. Roughly, they consist of better timelines, realistic goals, uniform metrics, and standardizing the way the FAA thinks about drones.

It’s a long road to the future of drone-filled skies. This report is the surest sign yet that 2020 is too optimistic a date for drone integration. If the FAA follows the steps recommended, and if the technology develops on schedule, there’s still a chance for a drone-tastic future, but it’s going to take a lot if work and a lot of change by the agency to get there.