In South Florida, more frequent and destructive flooding due to climate change has become a serious problem. This March 19 report by the PBS News Hour and WPBT looks at how communities like Miami Beach and Broward County are trying to adapt their physical systems to stand up to the new reality.

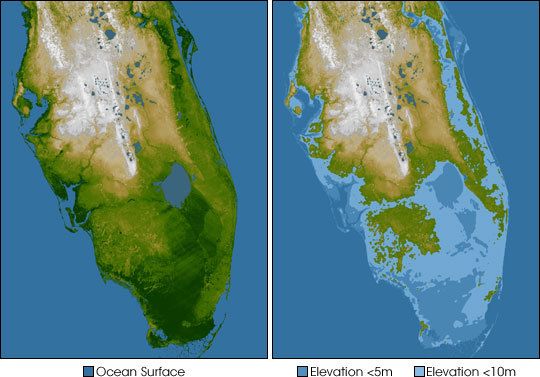

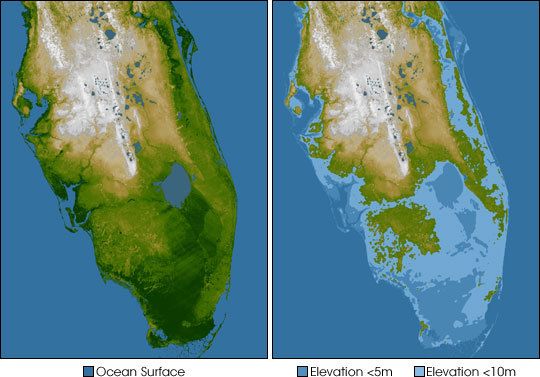

The drainage infrastructure on the Florida coast has relied upon gravity to draw rainfall runoff from higher canal levels to lower sea level, according to the report. But warming temperatures are raising sea level too high for these systems to work, by expanding the size of water molecules at the ocean’s surface, while also melting glaciers that historically kept much of the world’s fresh water locked away from the ocean. Climate change is also causing briefer but torrential rainfalls, creating more runoff than the drainage systems were built to handle all at once.

The first words in the segment, spoken by fishing boat captain and Florida native Dan Kipness, set a pragmatic tone. “Captains are used to looking at the ocean,” says Kipness,

South Florida elected officials have formally accepted a projection by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, that sea levels will rise three to seven inches by 2030, and nine to 24 inches by 2060. Unabated, these changes would pretty much wipe out Miami Beach before the end of the century. But having that political capital in place has allowed public works departments to take on retrofits of sewage, roadway, and water treatment plants to handle the changing environment. Costs are already high and likely to increase: Miama Beach’s existing storm water management master plan will run $200 million over the next 20 years just to keep pace with sea level rise, according to the report, and recently “commissioners for the city of Miami Beach voted on measures that are expected to double to $400 million, the cost of keeping water out of its city streets.”

The political situation is about as fraught as the environmental, however. “One of the biggest challenges we have in South Florida and across the country,” Richard Grosso tells the reporter, “is this disconnect between the best long-term investment and economic strategies for a community vs. a political process that is short-term in terms of its rewards.” Grosso, the director of the Environmental and Land Use Law Clinic and a professor of law at Nova Southeastern University, goes on:

Sea level rise and political uncertainty are not scaring people away from South Florida, apparently: According to a recent report by public radio station WBUR, home prices in the region have risen almost 10 percent in the past year.

Move away from the coasts, and climate change impacts are sometimes more subtle, but still real. As reported in this month’s print issue of Popular Science, a Boston University lab compared notes on Massachusetts flora and fauna written by Henry David Thoreau in the mid-1800s, to present-day conditions. Among their discoveries: trees leaf out a full month earlier, and wildflowers bloom three weeks earlier than in Thoreau’s day. The appearances of songbirds, bugs, and bees appear to be less affected so far.