There’s a long-held assumption that cancer is a universally progressive disease that will metastasize and kill its victims unless it’s stopped early. Since the 1980s, “Early detection is your best protection” has been a mantra of the cancer-awareness community, spurring an insistence on frequent screenings to catch ever-smaller abnormalities.

“In the screening process, nonaggressive cancers will inevitably turn up. The key is not to treat those.”

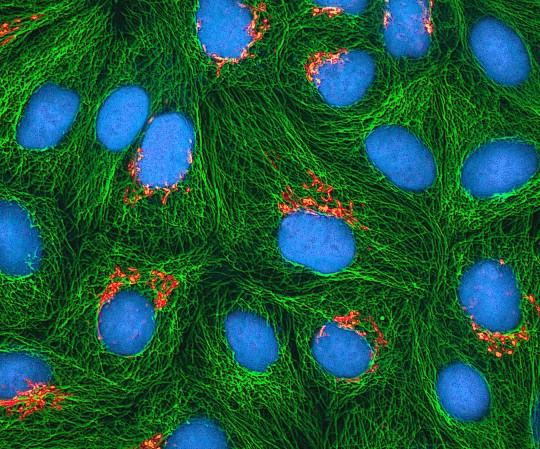

But finding cancer in the body doesn’t imply a death sentence. In fact, new research shows that its cell behavior is actually quite diverse. To oversimplify: Cancer is born when a cell harboring damaged DNA makes new cells instead of repairing itself or dying. At that stage, some cancers rapidly invade tissues even before they’re discernible. But others grow so slowly that they won’t spread to different parts of the body in a lifetime. Some even regress on their own. “The glands of the breast, the prostate, and the thyroid can all harbor a lot of small cancers that are detectable at autopsy but were not the cause of death,” says H. Gilbert Welch, a cancer researcher at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth.

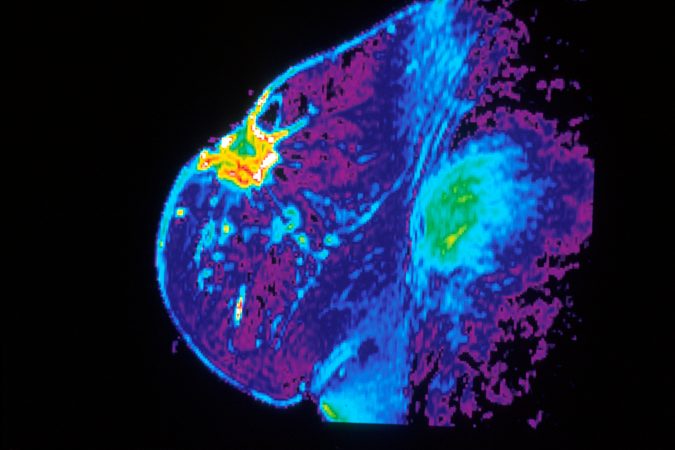

The problem is, we’re discovering too many cancers that don’t require action. Studies suggest that 22 to 54 percent of breast cancers found through routine mammography (and 23 to 42 percent of prostate cancers detected via prostate-specific antigen, or PSA, tests) were not fated to become life-threatening. Because it’s extremely difficult to distinguish between aggressive cancers and harmless ones during their early stages, we treat too many indolent cancers with surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy. That’s no trivial matter when these procedures can cost women their breasts or men their sexual function, not to mention the psychological toll of a diagnosis. And with the cost of treating cancer in the U.S. projected to grow as much as 39 percent from 2010 to 2020, that’s potentially billions of dollars for unnecessary action.

Let’s drop the goal of finding more cancers and realign the purpose of screening with its original objective: to save lives and reduce suffering. We should aim instead to find the right cancers—the potentially deadly ones stoppable with early treatment.

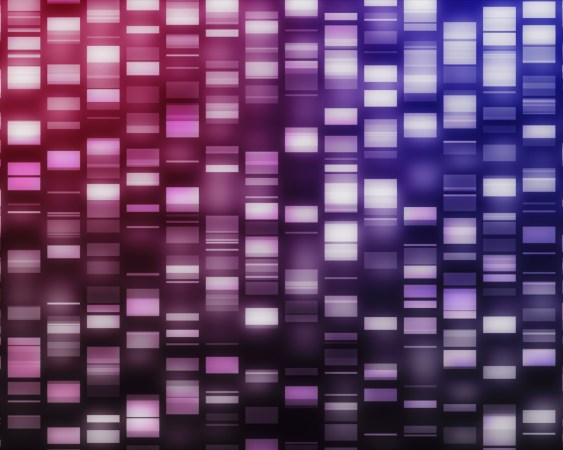

“In the screening process, nonaggressive cancers will inevitably turn up,” says Andrew Vickers, a prostate-cancer researcher at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. “The key is not to treat those.” Vickers has developed a test that uses molecular markers to flag which abnormal PSA results warrant further action. Other researchers are closing in on tests that can distinguish the genetic signatures of cancers most likely to become threatening from those that won’t.

Optimizing screening intervals would also help. In 2012, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s recommendations for cervical-cancer screening fell from annually to once every three years. They discouraged PSA screening altogether. The new standards offer nearly identical benefits in terms of saving lives.

The reality is that the most aggressive cancers usually turn up in the form of symptoms, not screenings, says Welch. For the slow-growing cancers, he says, “we’ve overstated the need to act quickly and underplayed the diagnostic value of time.”

This article originally appeared in the August 2014 issue of Popular Science.