It’s gross and it works.

Officially known as fecal microbiota transplantation, or FMT, the technique is exactly as described: fecal matter from a healthy person is placed into one suffering from chronic gastrointestinal disease. Though the practice has been around since the 1950s, there was little to no mainstream acceptance until recently. Today, FMT has become a widely discussed medical procedure forcing regulatory bodies such as the FDA to find ways to make it widely available.

The rapid rise of FMT popularity https://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/55/12/1659.long// has been remarkable considering the aesthetically unappealing prospect of using feces to cure disease. Yet over the last decade, medicine has come short in resolving some significant gastrointestinal diseases including ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel syndrome and other inflammatory bowel diseases. Intervention has proven to be one of the safest and cheapest options for those who appear to have no resolution if only to manage these conditions. But the real potential has been primarily focused on one rather nasty infection: Clostridum difficile.

Though much has been said about the successes of fecal intervention against C. difficile, one of the more prevalent studies was reported in 2013. A European group of researchers successfully cured infection in 15 of 16 cases with little to no adverse effects. The impact was almost immediate – FMT went from being one possible option to perhaps the only option. But there was a problem, particularly for regulators. While there was clinical benefit, the authors did not present any information on how the disease was cured. In order for this practice to be widely approved, there had to be a mechanism.

Later that year, a team of researchers from Maryland offered some perspective on the inside workings of treatment. They focused on individuals who had multiple relapses of C. difficile infection and examined their fecal matter both before and after the intervention. They found success was not due to the presence of individual or small groups of bacterial species. Instead, diversity was the key factor. In all cases in which the infection was resolved, the common change was in the increase of the variety of bacteria found in the fecal matter. Although the recipients never quite reached the same level of microbial richness as the donors, there data clearly showed a major shift towards improved diversity.

Even as this information was critical to understanding the change in microbial nature, there was still the issue of how exactly this change happened on a functional level. In the development of a mechanism, this was a critical need to ensure the entire picture is clear. This past week, a team of American researchers added even more credible evidence to demonstrate just how FMT works and why it does so well.

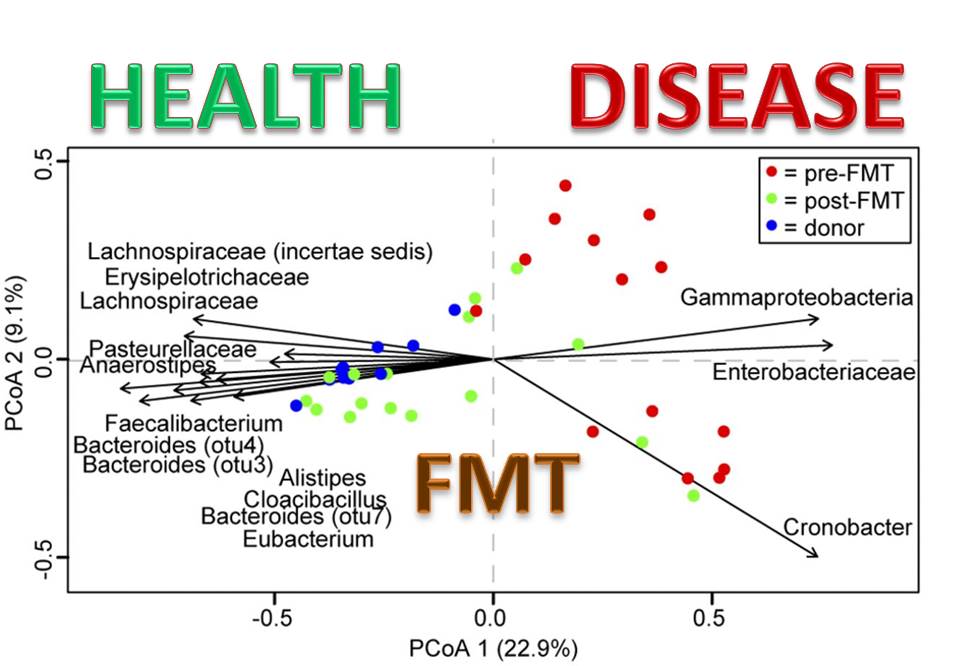

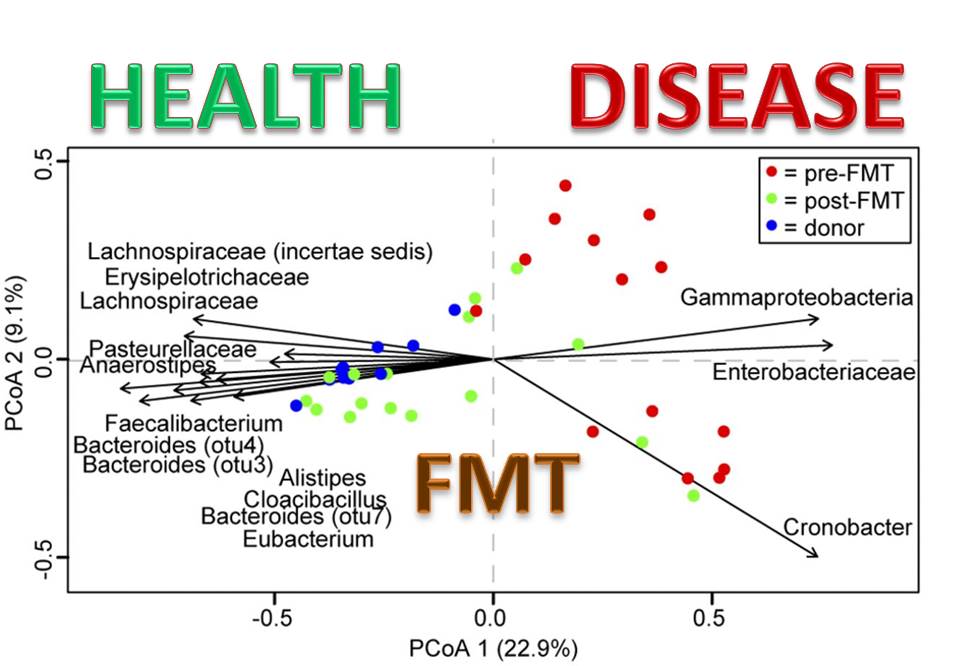

As with the 2013 study, the team focused on those individuals who had suffered from several C. difficile infections. They also studied the nature of fecal matter from both those who donated as well as recipients both before and after intervention. The results demonstrated a significant shift in the nature and diversity of the feces after transplantation. The difference was in the depth of study. When the team took the samples back to the lab, they went as far as they could to identify specific types of bacteria known to be involved in either health or infection.

The process of identification was genetic in nature allowing for an inspection of the entire bacterial population. With that accomplished, they then went hunting for signs of change. While there were several shifts seen in the nature of the bacteria, a few were indicative of the changes occuring deep inside the body. They included in addition to an 86% clearance of _C. difficile _symptoms:

- a loss of Cronobacter, known to cause a plethora of infections particularly in neonates;

- a loss of members of the Proteobacteria, which are associated with inflammation and the onset of C. difficile infection;

- an increase in the normal microbial flora Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes;

- an increase in the Lachnospiraceae family, a recognized member of healthy gut microbiota

- an increase in Akkermansia, a mucus-degrader in the human gut known to be associated with healthy individuals and thought to be involved in the prevention of obesity and colitis.

The observations suggested intervention allowed bacteria more harmonized with the human gastrointestinal tract to find a home and re-colonize the lining. Mechanistically speaking, the team had revealed how over a short period of time, the entire structural landscape benefitted from FMT and that even in as little as a few weeks, C. difficile could be remedied solely by using good germs.

The results of this study and a collection of others show FMT is here to stay as a remedy for infection and possibly other diseases. While the practice may not be widespread at the moment, considering the continuing rise in people suffering from gastrointestinal disorders, there is every reason to believe the practice will be as common as many ambulatory surgeries. This can only help to calm fears for those suffering and offer them hope for a not-too-distant future when they can finally have a practical, effective and inexpensive resolution.