Q&A With SciBabe On GMOs, Swearing, And More

Science blogger Yvette d’Entremont fights pseudoscience with snark

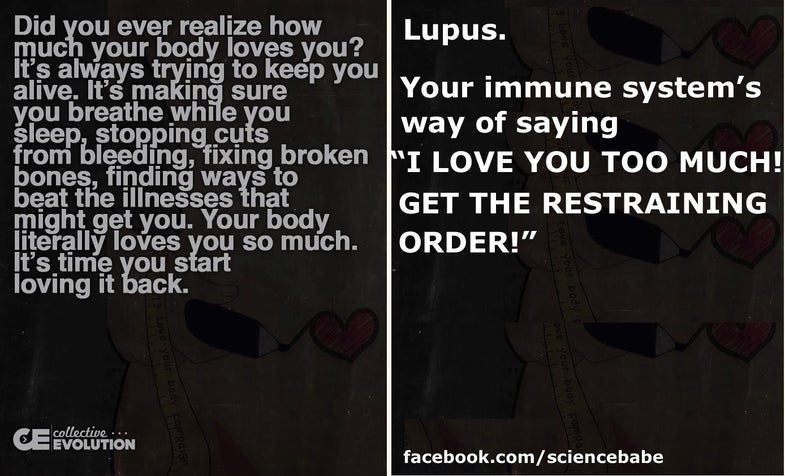

Earlier this month I was traveling in California for work, and during one stop I attended the 1st Annual Institute for Food and Agriculture Literacy Symposium at UC Davis. One of the speakers at the symposium was Yvette d’Entremont, a blogger and writer briefly known as the Science Babe and now known as SciBabe. I first heard of d’Entremont in April when she wrote a post for Gawker about Vani Hari, aka the Food Babe, a popular and controversial food blogger. The tone of the piece is clear from the title: “The ‘Food Babe’ Blogger Is Full of Shit.”

It went viral: As of today, the post has more than 4.6 million views and 3,319 comments. Among science and health writers, though, the reactions were pretty mixed.

During her talk in Davis, d’Entremont said two things that struck me. One was her theory on using snarky humor as a vehicle for science communication—the same tone that divided readers on her Gawker piece. The other was the fact that she used to be adamantly anti-GMO, in part because of a health scare, which sounds a little like the Food Babe’s own origin story.

So why have these two women (I’m not a big fan of the “babe” monikers, to be honest) end up with such divergent views on food? I spoke with d’Entremont on the phone recently to better understand how her views changed. We also talked about her new projects, a recent Twitter spat with the founder of IFLS, and why she swears so much.

Below is a transcript of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

BB: So before SciBabe, what were you up to?

Yd: I have a BA in theater, a BS in chemistry, and a Master’s in forensics, and I really wasn’t using the theater degree. The other two, I had worked since I got out of grad school. I taught college for a year. I’d gone on after that to work as an explosives chemist for a homeland security contractor, then worked as a toxicology chemist for four years, and then most recently worked as an analytical chemist for a pesticide company. And I started the blog when I was working there, and it’s partially because I kept seeing really bad information online about pesticides. People kept saying things are being doused in them.

I’m like, I’m telling you, this isn’t how it works. I see really horrible information about science on the Internet. So I started to combat that. I never thought that it was going to become a full-time thing.

BB: So, that was right after the Gawker article?

Yd: It was last November. I did a YouTube video where I downed an entire bottle of homeopathic sleeping pills, just to prove that they’re just sugar, that they don’t work, and it went kind of viral. There were about a third of a million views on it, and that was where a literary agent found me. So that was last October. The Gawker article came out in April, and at that point I’d been doing this for about seven, eight months.

BB: When I saw you speak in Davis, I was surprised to hear that you used to be pretty adamantly against GMOs for a variety of reasons. Now your writing has the opposite slant. Why did you feel that way back then?

Yd: I fell into all the propaganda that I side against now, is what it came down to. This is part of the reason why I tell people if someone is against GMOs and against vaccines, don’t look at them as somebody who’s stupid, and don’t look at them as somebody who can’t understand your point of view. They’re somebody who got bad information. Give them the right information, and give it to them in a way that, the other side is giving them little bitty sound bites and little bitty memes online. That’s how we have to fight this battle. I mean, part of the reason I fell into some bad information with GMOs, I was really, really sick.

I got the worst headache of my life, and it never went away. And you know, there’s probably years of struggling with doctors and medications, and the first eight months of that were just a living hell of not having the right medication combo, trying to figure out if it was a dietary thing, just struggling, and I went through all the different food blogs and health blogs, and they all said, “You did this to yourself. It was your horrible diet. Go vegan, go organic,” and I’m like, “Maybe this will save me.”

I think people fall for this out of desperation of looking for answers and wanting to improve their health. And you know maybe, partially a little bit of suspicion of the science that they don’t understand. So there are a lot of reasons why people fall for the bad information on GMOs, and I think that if we are given a chance to understand good information and don’t just go, “Well, they don’t understand it, they’re in the crowd against us,” like I said, these are the ones that march against Monsanto crowd, there’s people who wake up on a Saturday and march in the streets about food. These are passionate people. Give them the right information. You know, I was almost one of them.

BB: What changed your mind?

Yd: It was a combination of things. Partially that I finally got a right diagnosis on my headaches and the right medication, and realized that I could eat GMOs and didn’t give me headaches, but it was partially Penn & Teller’s show “Bullshit,” and watching their episode on GMOs. I think communicating the science with humor was such an effective tool on me. Whenever I saw the argument online that these things aren’t tested for safety, I realized in my own pesticide lab that I was working in, we were. I’m like, “How can these not be tested for safety when my exact job is testing for safety?” And sometimes I spent two weeks calibrating one instrument, and I’m just one cog in a machine. And I know the other sides are just as meticulous as I am. So it was kind of a turning point, seeing it in my own lab and seeing it communicated with some humor from Penn & Teller. It really did bring it all together and make me realize that there was a lot of bad information out there.

BB: After the Gawker piece, I noticed very different reactions on Twitter. Some people were sort of chortling, saying, “This is great,” or “This is funny,” or “Way to go.” And I also saw people who didn’t like the snarky tone. So I was curious, what happens if an audience doesn’t like your brand of humor? What if it’s off-putting to them in some way—is that something you consider, worry about, or think about when you’re writing?

Yd: I’ve learned not to worry if somebody doesn’t like my brand of humor. If somebody doesn’t like what I do, they can find someone else to listen to. If I water down how I work, if I try to change it, then it becomes—I keep on being told by everyone who I’m writing for, “Don’t change how you work, in terms of the writing, because there’s something good here.” There’s a distinct voice in how I write. If I’m writing a more serious piece, I’ll tone down the swearing and tone down the snark, but for the type of writing I’m doing on Gawker, the type of writing I do for my blog or for my book, I’m exactly in my wheelhouse. And if somebody doesn’t like it, there are a lot of other wonderful science advocates out there.

BB: And as far as the persona SciBabe goes, at what point did that emerge, and why that particular persona?

Yd: It’s not, how to phrase this, it’s not really a persona so much as it’s just me.

BB: So do you consider this to be an online persona, or is there no separation? Are you in fact SciBabe?

Yd: I’m not the woman behind the mask. I guess there’s not really a mask. I mean, I think I kind of ham it up. I know I said earlier, my theater degree collected dust for a long time. This is kind of, it’s kind of me, a little bit of funny and a little bit of, how to phrase this? It’s adding jazz hands to science, although that’s an oversimplification. I think the difference between SciBabe—I’d say there’s a hair-width of difference. I think that’s what makes it work, that I’m not faking anything here. You see what you get. When you’re looking at the type of humor I put in there, it’s not put-on. It’s just this type of writing, this type of personality that goes on the page. It’s just me.

So, I mean, I am a scientist. I am kind of a goofball. When I was in college, I felt like I was kind of too science-y for the theater kids and too theater-y for the science kids, so somehow SciBabe is kind of a perfect amalgamation of what I do, and what my brain likes. So I think it’s just really me.

BB: Okay. And is this SciBabe name, is that an answer to Food Babe, or was that something entirely separate?

Yd: There was kind of an answer. Like I said, I didn’t think this was going to become a career, and I kind goofed. At first, it was Science Babe. I didn’t realize there was already a Science Babe. We had a phone call, and I apologized profusely.

BB: Is that why you changed it to SciBabe instead of Science Babe?

Yd: Yeah, and I asked her if SciBabe was okay, and she said yes. Her name is Debbie Berebichez, and we’re both speaking at a convention in a couple weeks. I’m looking forward to taking her out to drinks and apologizing for all the mail she’s had to redirect to me. I’m very sorry about that, but it was direct poke at the Food Babe. I mean, it was just supposed to be a little Facebook page. I didn’t think that I was going to be sitting at home writing a book, less than a year later. This was not the plan, so yeah, direct poke at the Food Babe, not in the long-term plan.

BB: So what’s the SciBabe philosophy?

Yd: I think the tag line, “Come for the science, stay for the dirty jokes” is a perfect summary of what I do. I mean, it’s science, with a bit of snark. And I mean, it’s also breaking down, telling people how to be able to tell if something is real science or not. That’s a huge focus on it, because sometimes I’ll post science links, but the biggest thing I do is break down why something, break down why something isn’t science, because I go after pseudoscience quite a bit. And I don’t just tell people, “This is bullshit.” I’ll tell people, “Here’s how you can tell if somebody is bullshitting you,” and arming a consumer to be able to not waste their time or money on a product that’s bad science. That’s kind of the focus of my book, and that’s kind of become more the focus of my site over time.

BB: And yesterday, I saw you interacting with Elise Andrew from IFLS. What happened there?

Yd: I like what she does on her site overall, and I love that in the course of the day, somebody who might not get any science whatsoever is going to see a science article or two by following her site. What I don’t like is occasionally I’ll see something on her site just very much in opposition to scientific consensus, and I’ve seen this a few times now between colony collapse disorder. Like, the causes of that are not, it doesn’t seem to be linked to the neonicotinoid pesticides. It seems to be linked more to varroa mites and a couple other conditions. I mean, just showing how one Tweet, I got 3 million nasty Tweets back from her, and I looked on her entire Twitter feed. It’s not very positive.

BB: So you mentioned a book. Tell me about that.

Yd: I’m working on a book: “SciBabe’s Ten Rules to BS Detection.”

BB: Ten rules to what?

Yd: BS detection, BS meaning “bad science,” but of course they have to try to say something will get attention. But I also, as you’ve noticed, I’m quite comfortable using a little bit of bad language here and there. Part of the reason I do that in my articles in because it keeps me safe from lawsuits. So calling someone, I don’t know if you’re going to be able to publish this, calling someone a bullshitter, as opposed to calling them a scam artist, keeps you out of lawsuit territory. It’s part of the reason why I use the term bullshit so much.

BB: Interesting. I’m not sure if that’s how defamation lawsuits work—if you just swear, I don’t think that protects you from a lawsuit.

Yd: It’s worked for me so far. But I mean it’s partially, you know, there’s, what’s the legal definition of “asshole”? I mean, you can swear at someone all day long, but as long as, I think there are a handful of words, there’s a legal definition of them. Like, if you call, if one is to call someone a fraud, that’s, or a liar, there’s a legal definition to that. If one calls someone an asshole selling bullshit, you’re pretty safe. I mean, someone can, there are probably ways they can hit you with a slap suit, but most of the time, you’re going to be able to get that dismissed.

As long as you preface it with, you can preface it with, “In my opinion, this is what this person is doing,” and you’re fine.

[Note to readers from Brooke: Before taking this approach, I suggest brushing up on libel and slander definitions and law]

BB: When’s the book out? And what else is next?

Yd: It’s due December this year, so it should be out in winter of 2016 or spring of 2017. More articles for Gawker, more writing on my own site. I’m doing some TV appearances now, and I have some other stuff in the works I can’t talk about yet, because I’m at the weird stage of my life where I have people. I keep looking at this going, “I’m just a little kid from New Hampshire who never thought I was going to make it anywhere.” Now I have people, it’s very weird. I’m at a very strange point in my life, and I’m enjoying it.

BB: Well, that’s it—thanks for chatting, I appreciate your time.

Yd: No problem. Thank you so much.