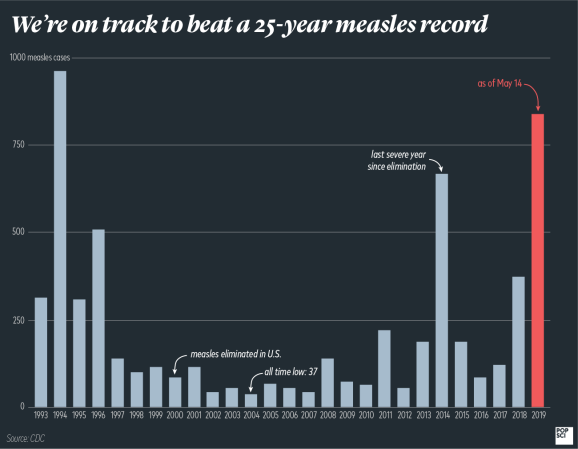

It’s been nearly two decades since the U.S. officially eliminated measles, but we may lose that status before we hit the 20-year mark.

This week, the Department of Health and Human Services announced that we’ve now topped 1,000 cases in 2019. Elimination isn’t about case numbers, though, it’s about time—and just last week, the Director of the CDC warned that we could be in danger of losing our status as a measles-eliminated country.

What does it mean to lose elimination status?

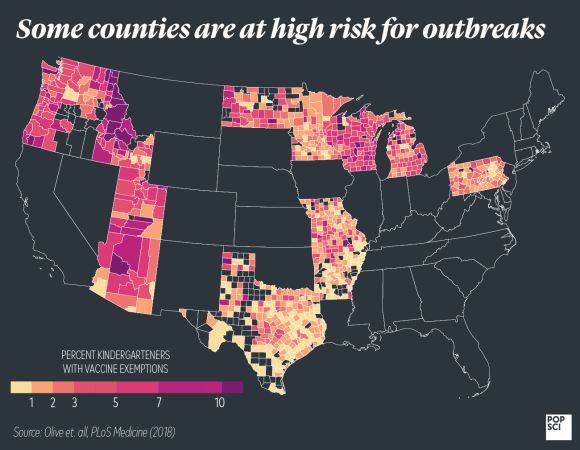

The World Health Organization defines “elimination” as the absence of endemic measles—meaning continuing transmission of the disease within the country—for more than 12 months. If someone entered the country with measles and spread it to a handful of people, that’s not endemic transmission. But if those infected people then spread it to other folks in the U.S., those would be considered endemic cases.

Though we only really started to hear about them recently in the news, the ongoing outbreaks in New York State have been raging for the past eight months. That puts us just four months away from potentially losing our status.

If we do lose it, it wouldn’t just be a question of stopping these outbreaks. We would have to go at least another full year with no endemic transmission of the disease.

How bad would it be for measles to come back?

It’s easy to fearmonger here and cite statistics about how 500 people, mostly children, died annually in the U.S. from measles before the vaccine was available. Measles used to account for one in five deaths of kids under five years old. Roughly 48,000 people would be hospitalized, and 3 to 4 million total would fall ill.

The truth is, we’re not going to jump back to that state. Even though we never achieved our target goal of 95 percent immunity, the U.S. as a whole still reaches above 90 percent—making it almost impossible for us to reach 1950s-level measles anytime soon.

But the truth is, it’s been so long since measles was a routine childhood disease that there are genuine concerns about what would happen if it came back. Though the virus ravaged many, most of the kids who got measles grew up to be adults who couldn’t get infected again. Vaccines don’t necessarily provide that extremely high level of immunity, though, and we now have an older population that hasn’t been exposed to the constant circulation of measles—it’s possible those people could be susceptible in ways we haven’t yet seen.