Lidar, a way to use laser light to measure how far away objects are, has come a long way since it was first put to work on airplanes in 1960. Today, it can be seen mounted on drones, robots, self-driving cars, and more. Since 2016, Leica Geosystems has been thinking of ways to apply the technology to a range of industries, from forensics, to building design, to film. (Leica Geosystems was acquired by Swedish industrial company Hexagon in 2005 and is separate from Leica Microsystems and Leica Camera).

To do this, Leica Geosystems squeezed the often clunky, 3D-scanning lidar technology down to a container the size of a soft drink can. A line of products called BLK is specifically designed for the task of “reality capture,” and is being used in a suite of ongoing projects, including the mapping of ancient water systems hidden beneath Naples that were used to naturally cool the city, the explorations of Egyptian tombs, and the modeling of the mysterious contours of Scotland’s underground passages, as Wired UK recently covered.

The star of these research pursuits is the BLK360, which like a 360-degree camera, swivels around on a tripod to image its surroundings. Instead of taking photos, it’s measuring everything with lasers. The device can be set up and moved around to create multiple scans that can be compiled in the end to construct a 3D model of an environment. “That same type of [lidar] sensor that’s in the self-driving car is used in the BLK360,” says Andy Fontana, Reality Capture specialist at Leica Geosystems. “But instead of having a narrow field of view, it has a wide field of view. So it goes in every direction.”

[Related: Stanford researchers want to give digital cameras better depth perception]

Besides the BLK360, Leica Geosystems also offers a flying sky scanner, a scanner for robots, and a scanner that can be carried and work on the go. For the Rhode Island School of Design-led team studying Naples waterways, they’re using both the BLK360 and the to-go devices in order to scan as much of the city as possible. Figuring out the particular designs ancient cities used to create conduits for water as a natural cooling infrastructure can provide insights on how modern cities around the world might be able to mitigate the urban heat island effect.

Once all the scans comes off the devices, they exist as a 3D point cloud—clusters of data points in space. This format is frequently used in the engineering industry, and it can also be used to generate visualizations, like in the Scotland souterrain project. “You can see that it’s pixelated. All of those little pixels are measurements, individual measurements. So that’s kind of what a point cloud is,” Fontana explains. “What you can do with this is convert it and actually make it into a 3D surface. This is where you can use this in a lot of other applications.”

[Related: A decked out laser truck is helping scientists understand urban heat islands]

Lidar has become an increasingly popular tool in archaeology, as it is able to procure more accurate dimensions of a space than images alone with scans that take less than a minute—and can be triggered remotely from a smartphone. But Leica Geosystems has found an assortment of useful applications for this type of 3D data.

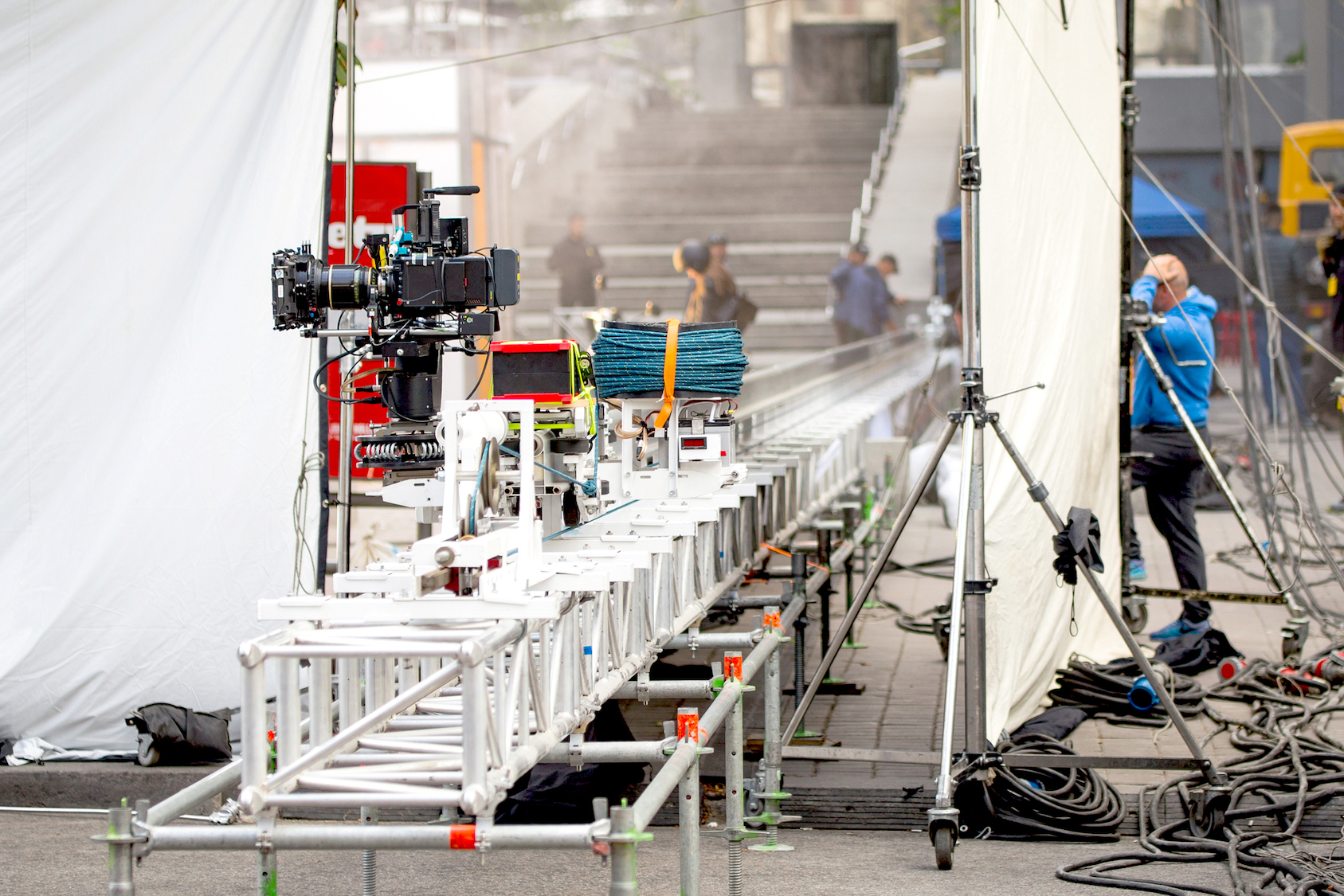

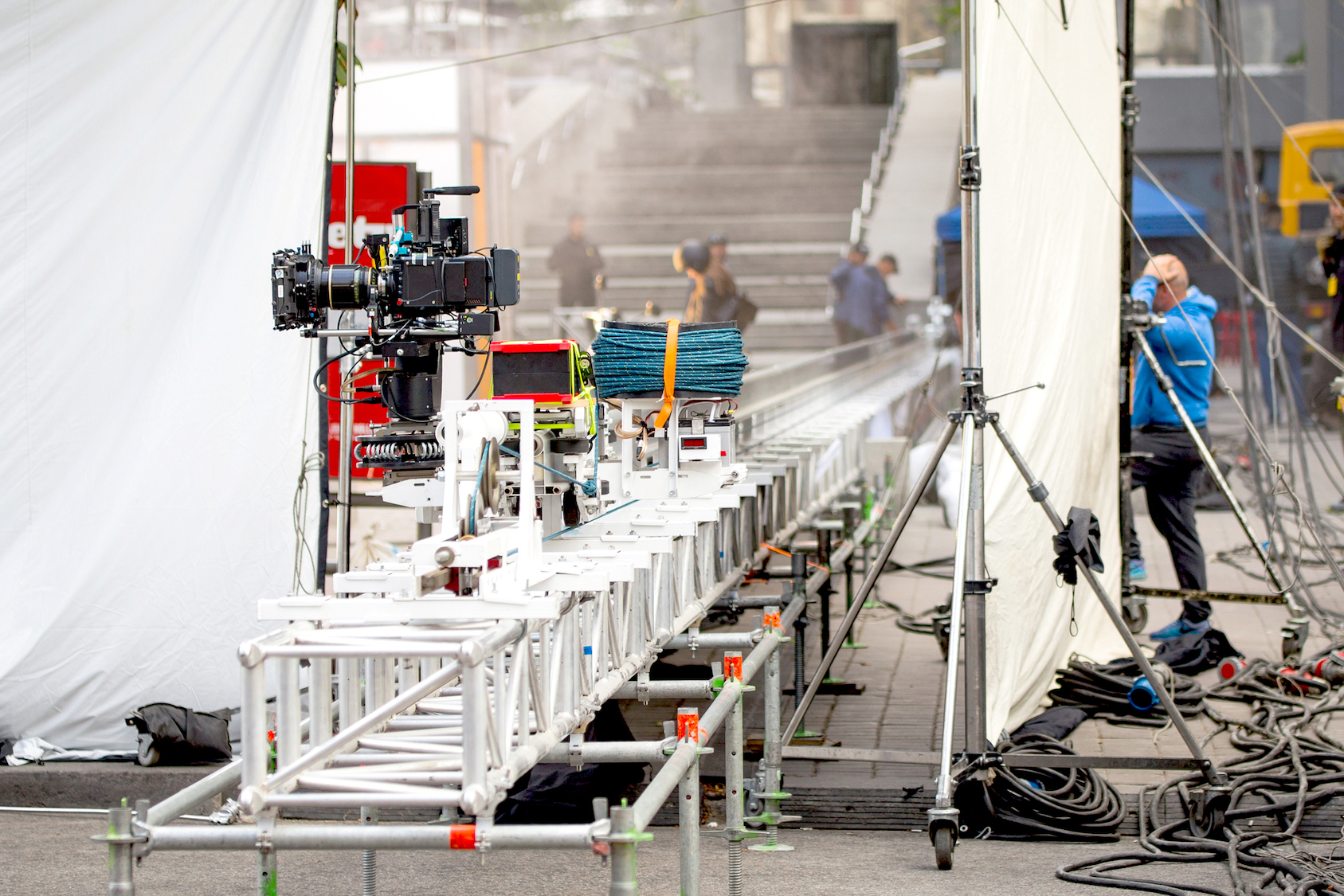

One of the industries interested in this tech is film. Imagine this scenario: a major studio constructs an entire movie set for an expensive action film. Particular structures and platforms are needed for a specific scene. After the scene is captured, the set gets torn down to make room for another set to be erected. If in the editing process, it’s decided that the footage that was taken is actually not good enough, then the crew would have to rebuild that whole structure, and bring people back—a costly process.

However, another option now is for the movie crew to do a scan of every set they build. And if they do miss something or need to make a last-minute addition, they can use the 3D scan to edit the scene virtually on the computer. “They can fix things in CGI way easier than having to rebuild [the physical set],” Fontana says. “And if it’s too big a lift to do it on the computer, they can rebuild it really accurately because they have the 3D data.”

[Related: These laser scans show how fires have changed Yosemite’s forests]

Other than film, forensics is a big part of Leica Geosystems’ business. Instead of only photographing a crime scene, what they do now is they scan a scene, and this is done for a couple of different reasons. “Let’s say it’s a [car] crash scene. If they take a couple of scans you can have the entire scene captures in 2 minutes in 3D. And then you can move the cars out of the way of traffic,” says Fontana. “That 3D data can be used in court. In the scan, you can even see skidmarks. You can see that this person was braking and there were these skidmarks, and they can calculate the weight of the car, compared to the length of the skidmark, to see how fast they were going.”

With more graphic situations, like a murder or a shooting, this 3D data can be used to create “cones that show a statistical confidence of where that bullet came from based on how it hit the wall,” he says.

As lidar continues to be expanded in tried and true applications, the growing variety of use cases will hopefully inspire innovators to think of ever more new approaches for this old tech.