Current EV Motors Founder Rocco Calandruccio grew up surrounded by cars; his grandfather opened a Ford dealership and then a Buick dealership and collected vintage and sports cars throughout his life. Calandruccio’s family lived in a rural part of Tennessee, where it wasn’t uncommon to find fields full of “rusting carcasses” of vehicles that had been abandoned when the engines or transmissions had failed.

Calandruccio had those rusted-out cars on his mind when he started his company. He wasn’t willing to accept that cars are disposable entities and set out to figure out a way to give them new lives. Centered on that goal, Calandruccio secured two patents for EV conversion kits. Internal combustion engines are complicated beasts with thousands of failure points, he says; he wants to provide a simplified, streamlined path to all-electric driving.

Here’s Calandruccio’s plan to bring EV conversions mainstream.

Bypassing the transmission

Crate engines have been available for decades. These fully assembled internal combustion engines provide a cornerstone for automotive restoration projects as replacement or power upgrades. You can buy a basic LS9 block with nothing else included, or opt for a package like Chevrolet’s “connect and cruise” setup that also contains a transmission.

Less common is what Chevrolet calls an “eCrate,” which includes a single all-electric motor and some of the elements you’d need to convert a gas-powered GM vehicle to an EV. The kit includes a low stall torque converter, transmission control module kit, flex plate, and hardware. Launched just this year, Chevrolet presents the eCrate as a motor “designed to connect directly to a GM 4-speed automatic transmission with an external mode switch.”

One defining aspect of the eCrate is the standard one-size-fits-all 66 kilowatt-hour lithium-ion battery pack. For scale, Chevy’s Bolt carried a 66-kWh battery for a little more than 250 miles of range. Now imagine you own a fleet company that only needs a range of about 50 miles per day; you’d be carrying a lot of surplus battery. That affects the range and can cost thousands more than a smaller, right-sized battery to match the vehicle.

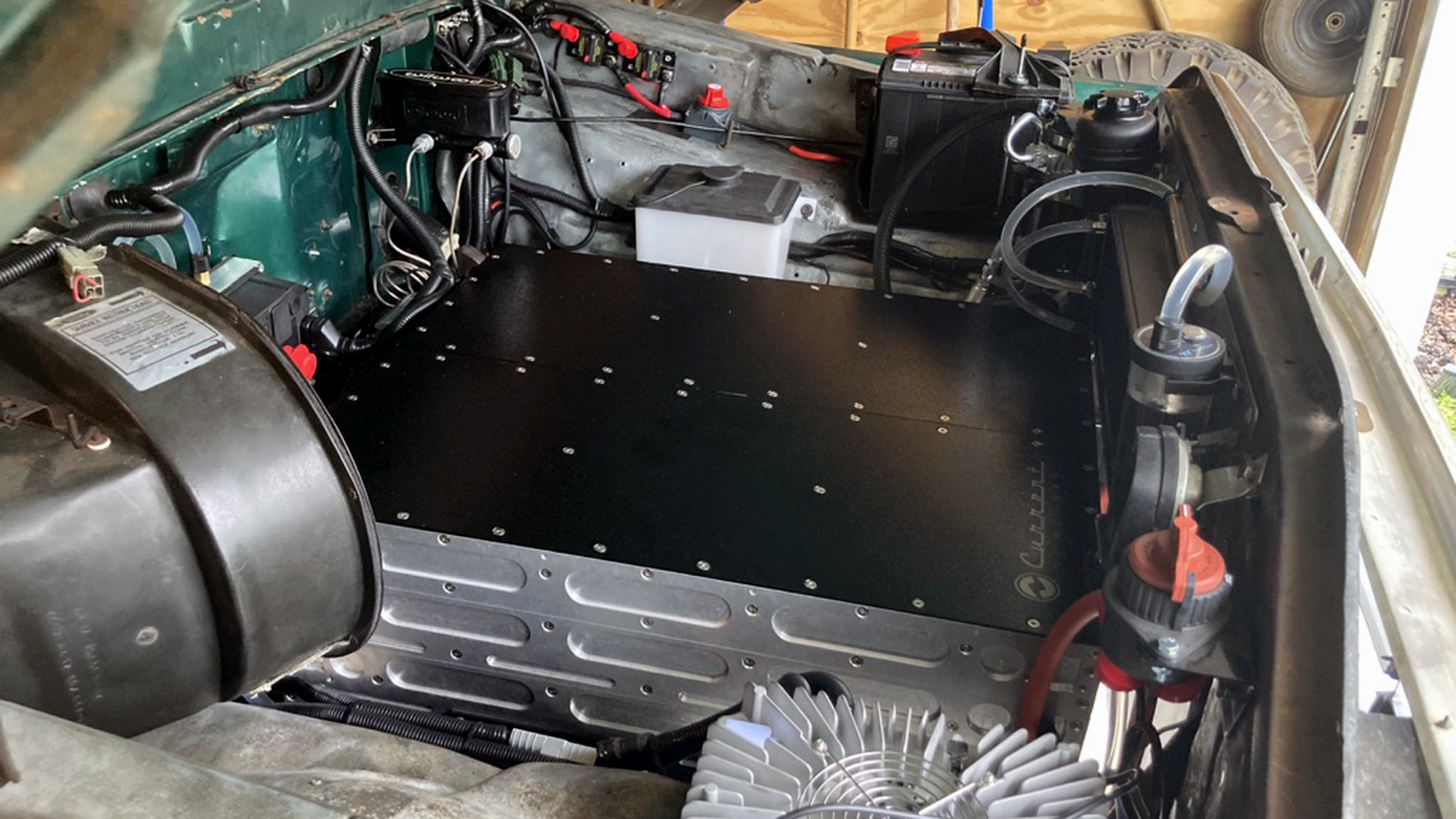

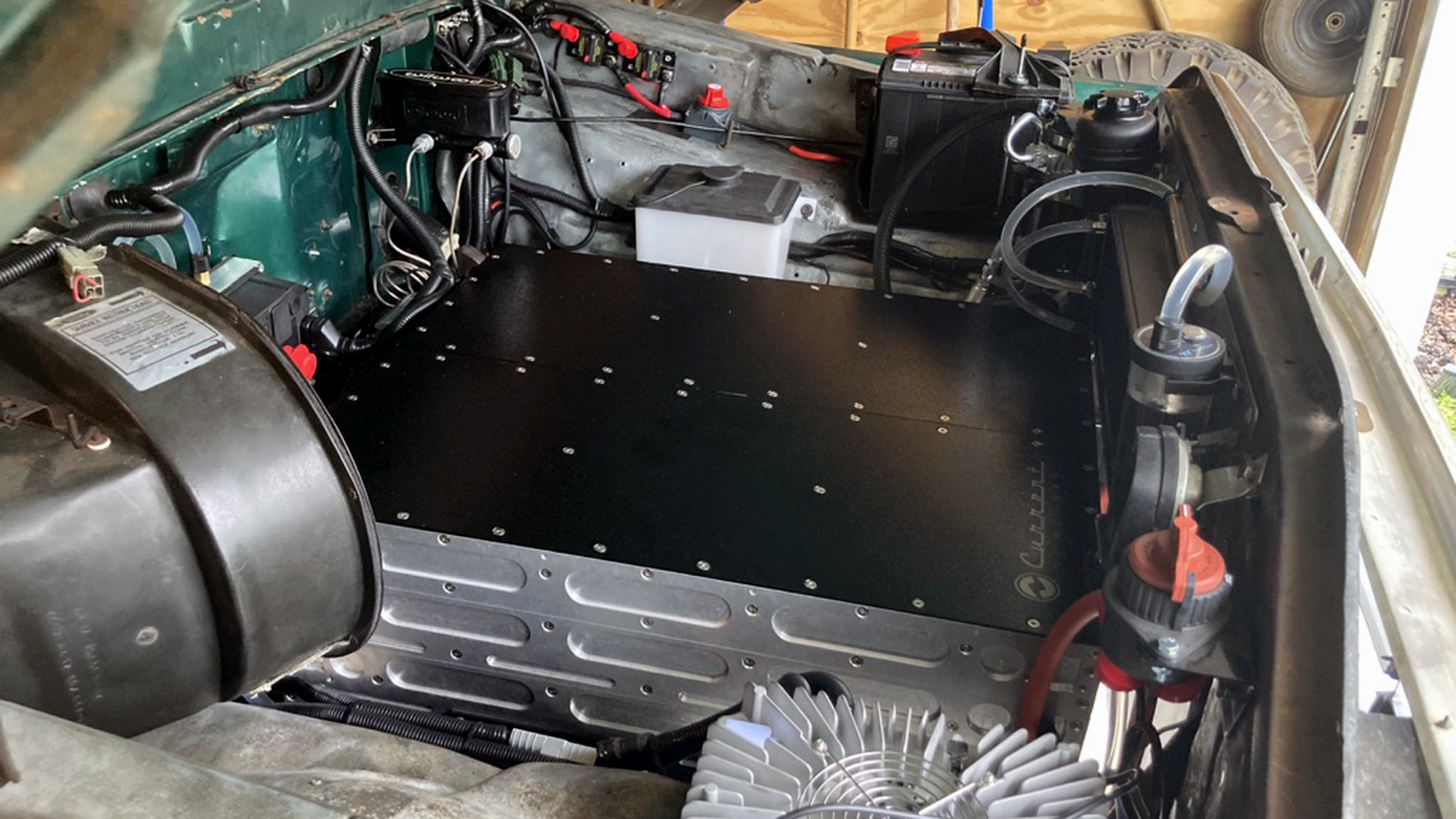

What Current EV is offering is more than a crate engine, Calandruccio says. His kit is instead engineered to bypass the transmission to improve the electric motor’s performance and efficiency. Instead of using a transmission to convert energy from the engine to turn the wheels, the motor is bolted directly to the axle.

“We’re focused on a bolt-on, all-inclusive solution for electrification,” he explains. “For this solution to be sustainable, it has to appeal to everyday mechanics and be safe, quick, and effective.”

Calandruccio’s marquee project is a 1978 Ford F-150 he named Gator for its signature green finish. A rolling example of what can be done when a solid mass-produced body meets an all-electric motor, Gator is one of about 10 million Ford trucks built between 1961 and 1978 on that chassis. That’s a key factor for Current EV, which plans to build kits in volume to bring the cost down. As a result, smaller conversion shops can complete projects in shorter amounts of time.

“We want this to be a solution that helps people in the EV industry see better margins and turn around more vehicles in their shops,” he says.

Quicker, easier conversions

One major challenge is that the conversion process isn’t typically a plug-and-play option. It’s a complex process to take a car designed to support an internal combustion engine; pulling the engine shifts the center of gravity one direction and adding a battery pack and motor shifts it again. Everything about the drive is effectively different, and that’s partially why it’s an expensive, customized undertaking.

EV West, a custom conversion shop in San Diego, California, converts classic and specialty cars into EVs. Even with costs topping $40,000 to $60,000 per conversion, CEO Michael Bream told U.S. News and World Report that his shop has a four to five-year wait list.

While individuals may be able to wait it out, some organizations cannot. Case in point: the University of the South in Tennessee wanted to convert a 12-vehicle fleet of Ford Econoline vans to continue shuttling students around campus. The university’s fleet was starting to age, and it became clear that replacement was necessary. Unfortunately, there was a multi-year wait for replacement vans, and swapping the old units for new EVs would cost between $80,000 and $120,000 each.

The listed starting price for a gas-powered Econoline is about $35,000, or $46,000 for Ford’s E-Transit all-electric van. That’s just a starting point, though, because those prices reflect the vehicle as a cutaway. Basically, a cutaway is a cab that seats two with a frame and axle behind it that can be fitted with a bus body and seats or even a box truck. Upfitting an interior can add tens of thousands of dollars to the invoice for each vehicle.

Instead, the university signed on with Current EV Motors for a cost of $35,000 to $50,000 per vehicle. A driving study uncovered the fact that the vans require minimal range, Calandruccio says, at less than 10 miles per day, so the conversion kits would price out on the lower end of that spectrum with smaller battery packs. As one of the most significant costs for an EV is the battery pack, that means the university could purchase what it requires without overspending.

How that translates to one-off conversions

The next frontier for Calandruccio’s company will be kits for vintage (model years 1964-1977) Bronco SUVs and Scouts. Incidentally, the classic Scout Motors relaunched itself not long ago as an EV company, and will be selling its own electric SUV and truck starting in 2026. Those with an older-model Scout on their hands might consider a retrofit if they don’t want to wait.

Meanwhile, Current EV Motors is actively working toward making EV kits easier and more accessible to more drivers while refreshing cars that might otherwise be put out to pasture. To do so, Calandruccio is working toward scaling production and on the hunt for investment partners or collaborators to scale operations and buy in bulk.

Calandruccio’s dream is for any mechanic or fleet maintenance staff to be able to swap out any gas-powered vehicle with a bolt-on kit. That’s the tipping point, he believes, toward larger-scale conversion rates.