This summer, billions of cicadas will rise from under the East Coast, shed their grub-like bodies, and clumsily fly to perches in trees, where they will make a terrible racket. The insects are singing to attract mates, but this year, they’ll have the ear of the U.S. Navy, too. Researchers at the U.S. Naval Undersea Warfare Center are dissecting cicadas in an effort to develop a better underwater sensor. Yesterday they presented a paper on their work at the International Congress on Acoustics.

The major mystery the Navy would like to solve: How does a bug so small create a noise so loud? The answer could have major implications for compact sonar systems. Although such systems currently exist, those are based on passive sonar, which can listen to other objects underwater generating noise, so long as the noises are louder than the vessel doing the listening. A passive sonar system cannot send out sound of its own to locate other vessels.

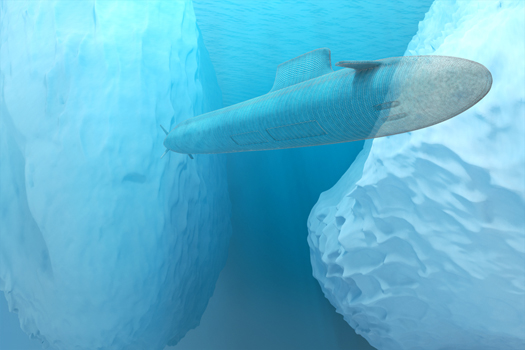

Active sonar systems, on the other hand, emit sound and then listen for sound waves that bounce back from underwater objects. Current active sonar systems require large and complicated equipment, which means not every ship can carry them. The Navy researchers hope that by replicating cicada noisemakers, small ships like unmanned underwater vessels could begin to use active sonar. An unmanned vessel with a cicada-inspired sonar system could locate hostile forces, while also appearing to be a far bigger, more distracting threat than it really is.

To understand the cicada song, Navy researchers are using lasers to track the parts of cicadas that make sound. Cicadas’ internal noisemaker consists of two parts: a pair of plates on their thorax, each of which are attached to ribs that bulge outward. Cicadas contract the plates, making the ribs click inward. A large air sac behind the ribs makes the sound reverberate in the same way that blowing air over an empty bottle creates a deeper sound. Cicadas bulge the pair of ribs over their air sac 300 to 400 times a second. Because the resultant sound waves are out of phase with each other, they somehow combine and amplify, thus creating the discordant rattle that animates the East Coast every 17 years.

Listen to Brood II cicadas below: