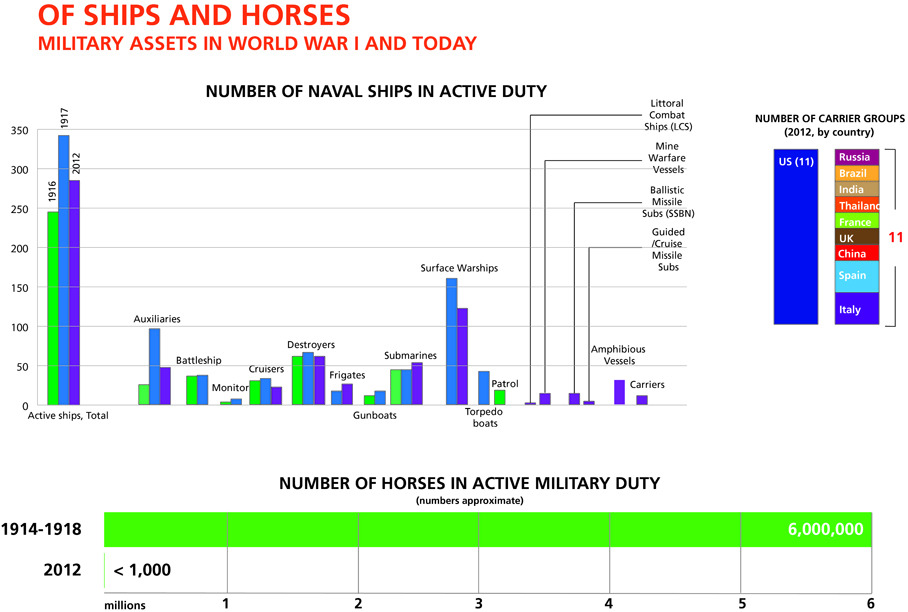

“Horses and Bayonets” was a meme the instant it came out of President Obama’s mouth during last night’s debate. The phrase was part of a rebuttal against Governor Romney’s claim that we’ve had the smallest number of ships since 1916 (the implication being that our Navy is currently weak).

It is true that we have fewer ships today than we did in 1917, but Romney misses the point entirely about the capabilities of the modern Navy and what other countries’ capabilities are. This does not just include the number of carrier groups currently deployed (or planned), but also an improvement in strike capabilities of the modern fighter-bomber (or drone) versus those of World War II. (There wasn’t much bombing in WW I, so that’s a pointless comparison to make.)

So, how does today’s US Navy match up? Are we are underpowered as Romney is suggesting?

Answer: No.

Clay Dillow elaborates:

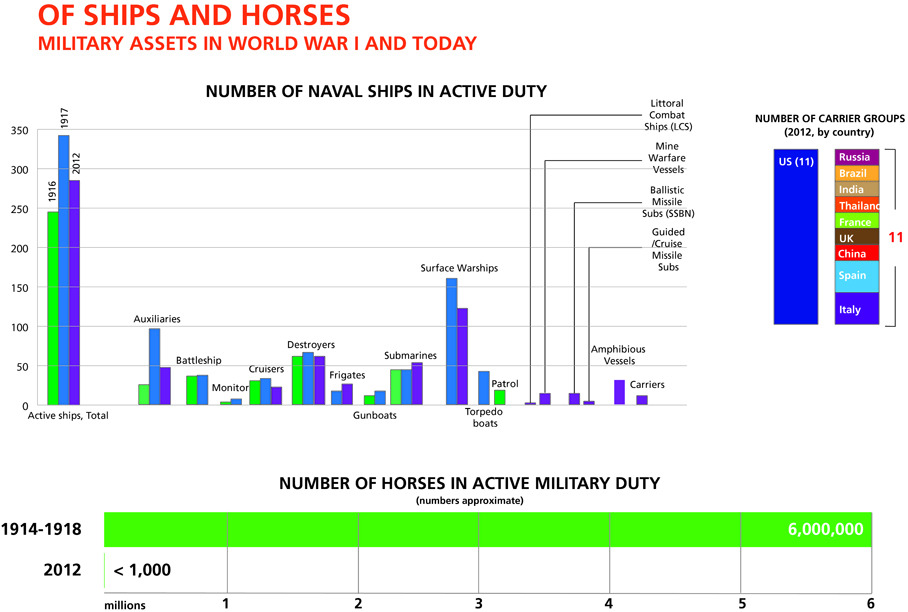

The U.S. Navy lists its active ship force at the end of 1916 at 245 total ships, a number that jumped to 342 the following year as the United States joined World War I in progress. At the end of 2011, the Navy officially lists its active ship force at 285 vessels.

So far, so good, Romney. From 1917 forward the number of actively listed ships fluctuates much like you might expect, peaking at the end of 1945 with nearly 7,000 active vessels, and troughing between periods of military conflict (though never dipping back below 300). Until, that is, the 2000s, when the Navy’s active fleet shrunk to its lowest level since the 19th century in 2007 under the leadership of George W. Bush. But Romney is comparing apples to oranges. His comparison, for the purposes of measuring the Navy’s strength, is meaningless.

Back in the first half of the last century, the Navy was a very different beast than it is today and the official ship accounting tallied a lot of ships that, by today’s standards, are not considered part of the active fleet. In 1916 there are battleships (36) and cruisers (30) on the list, sure, but there are also monitors, gunboats, steel gunboats, and torpedo boats–classes of ships that are either antiquated (seen an ironclad lately?) or that have been made redundant by advances in technology.

A single modern carrier group consisting of fewer than ten ships could easily sink the entire 1916 U.S. fleet. So not only are total active fleet numbers counted differently in 2012 than they were in 1916, but comparing the two doesn’t even give you a sense of what you really want to measure: capability against a militarily sophisticated foe.

In his book Wired for War, Peter W. Singer notes that during World War II the Allies needed roughly 108 planes to take out each target. They sometimes attacked targets over and over again until they were finally able to destroy them, as their unguided bombs and mid-century bombsight technologies weren’t exactly surgical in their precision.

In Afghanistan in 2001, each warplane averaged 4.07 destroyed targets per mission. Since World War I, technology has completely inverted the equation; instead of sorties per target, we now talk in terms of targets per sortie.

In other words, there are plenty of things for the presidential candidates to argue about this time around, but the strength of America’s Navy–especially as it compares to the strength of our Navy in 1916–is not one of them. America currently has 11 carrier strike groups at its disposal (we had zero aircraft carriers in 1916). That is the same number as all the other active aircraft carriers in the world combined.

If we’re simply counting how many ships are floating in the water, Romney’s math is correct, but that’s not how you measure the strength of a modern Navy.