One hundred years ago, the Panama Canal opened for the first time. A triumph of turn-of-the-century engineering, it connected Pacific and Atlantic, expanding the worlds of maritime commerce and re-writing the sea lanes of the Western Hemisphere.

But with the canal came one major constraint: size. The locks of the canal are only so wide and so long and so deep, and while much of the ocean itself is boundless in what its depths can accommodate, the canal is a finite place. The maximum size for a modern vessel that wants to use the canal is known as Panamax. A Panamax vessel can be no longer than 965 feet, no wider than 106 feet, may extend no more than 190 feet above the waterline or 39 feet 6 inches below it, and no more than 65,000 deadweight tons.

The limitation was seized upon by naval theorists as soon as it was created. In 1916, Commander William Adger Moffet of the U.S. Navy wrote about the possible maximum size of warships, and came pretty close to the Panamax limit. Popular Science reported on it then in “The Thousand-Foot Battleship”:

Included with the story was an estimation that the theoretical size limit of battleships was 995 feet in length and with a displacement of 60,000 tons. Moffet’s theorized ship would have been as long as the American battleships Oregon and Pennsylvania, which were in service at the time, stuck together end-to-end.

Shortly after the Great War, this limit became less an exciting space to fill and more a cage that impeded ship size. In response to submarine attacks during the war, British vessels attached pontoon boats around the outsides of many vessels (this is what’s known as “blistering” a ship). In a 1919 article, Popular Science wondered if blistering American warships would mean forsaking the canal:

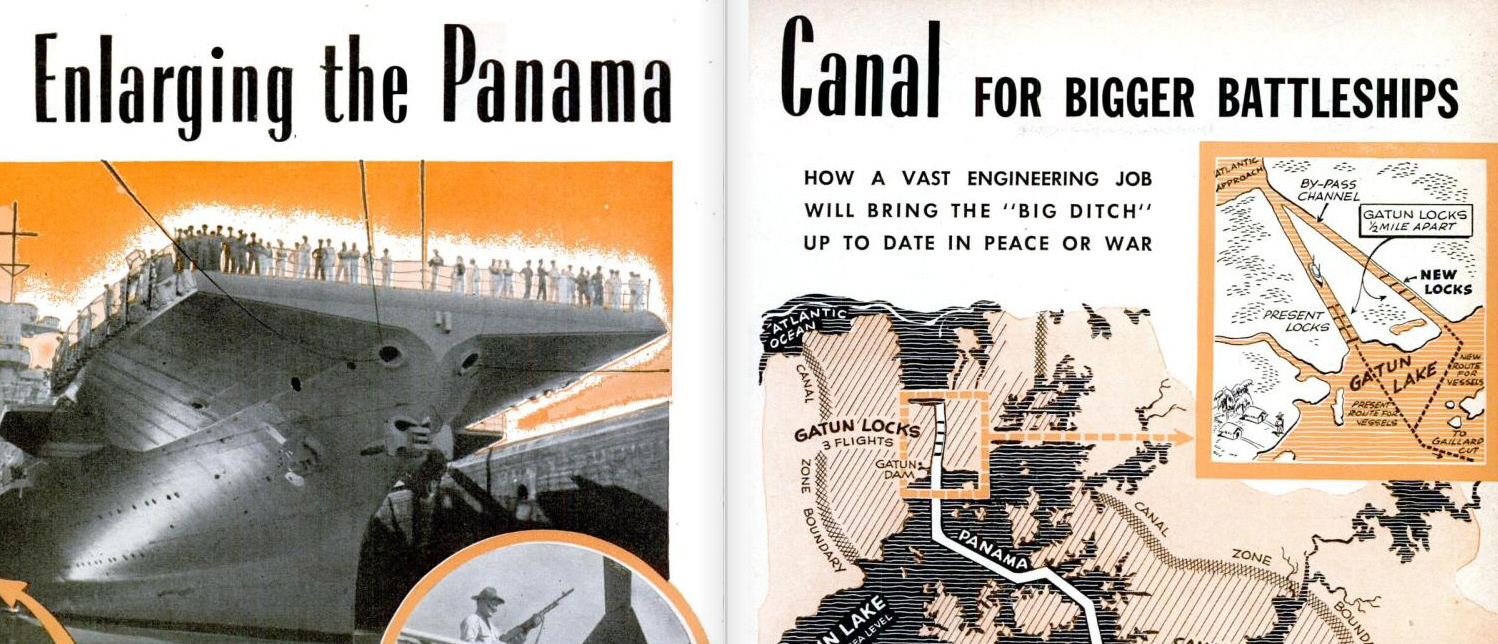

One possible solution to the narrow canal was adding another, larger set of locks. The United States, which completed construction of the canal and retained formal control over the canal zone for decades afterwards, attempted an expansion in the 1940s. The plan? Add a new set of locks at each entrance, and let more traffic traverse the main stretch of canal. “Enlarging the Panama Canal for Bigger Battleships,” in the September 1940 issue of Popular Science detailed this process, and explained the rationale behind it:

The project continued until 1942, when the demands of actually fighting the war caused the United States to cancel the project.

In the years since, most warships have remained within the constraints of the canal, but a few haven’t. The U.S. Navy’s Enterprise- and Nimitz-class carriers are all too big for the canal (at around 1100 feet long and 130 feet wide), and the new Gerald R. Ford class of carriers will be as well, even after the canal finishes its latest expansion project. Commander’s Moffet’s prediction was almost true: there was just one power willing to sacrifice the ability to send its ships through the canal, and that’s the same superpower that built it.