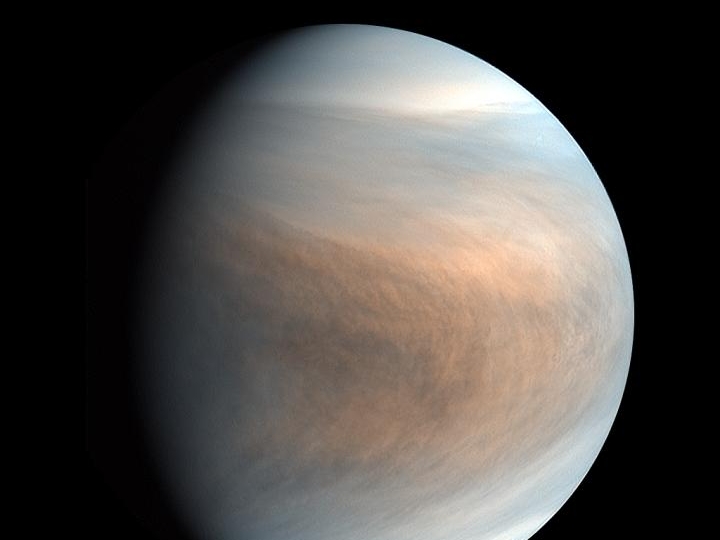

For decades, Venus has been considered a broiling, radiation-bombarded toxic hellscape of a planet in which nothing can survive. But now, in an unexpected twist, a group of scientists say they have found possible signs of extraterrestrial life in a place where few had thought to look: 30 miles up high in the planet’s yellow, hazy clouds.

An international team of researchers may have found tantalizing traces of phosphine, a potential sign of life, on the planet next door. “With high confidence, we have detected the phosphine on Venus, which was very unexpected and very exciting,” Jane Greaves, an astronomy professor at Cardiff University and lead author of the study, told reporters at a press briefing on Monday. “This is very encouraging for the hypothesis of life, but at the same time we are being very careful.”

Using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii and the Atacama Large Millimeter Array in Chile, researchers detected a spectral signature—a kind of chemical barcode taken from Venus’s atmosphere by reading its wavelengths of light—that is unique to phosphine. They estimated an abundance of 20 parts-per-billion of phosphine in Venus’s clouds, or at least a thousand times more than we find on Earth. The research, published today in the journal Nature Astronomy, not only has implications for Venus but the search for life beyond our solar system.

According to Greaves, phosphine is “ammonia’s evil cousin,” in that it’s extremely close in chemical composition. But, she adds, phosphine is a biomarker on Earth, found in some of its foulest places like dung heaps and swamps. It’s produced by life, but it is so reactive that it should disappear shortly after something crafts it. So you wouldn’t expect to see it in large abundances in an alien atmosphere unless life was constantly replenishing it.

Put simply, phosphine shouldn’t be in the Venusian atmosphere. It’s extremely hard to make, and the chemistry in Venus’ clouds should destroy the molecules. Researchers considered many alternate sources for what could be producing the gas, from lightning, volcanoes, and even meteors. Still, they settled on an explanation guided by what they know about our own planet: On Earth, if it isn’t being made by human industrial processes, phosphine is produced by microorganisms.

To be clear, the discovery is “not robust evidence for life” on Venus, emphasized Greaves. But natural sources of phosphine would only generate one ten-thousandth the amount actually detected. The presence of phosphine may yet be from some as-yet-unknown non-biological chemistry going on there, but scientists can’t rule out the possibility of a biological explanation. “It’s very hard to explain the presence of phosphine without life,” Greaves says.

“Planets can produce phosphine through ordinary geological and atmospheric processes. Known processes don’t work for Venus, so there must be a process we haven’t considered yet,” Andy Skemer, an associate professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz who wasn’t involved in the new study, told Gizmodo. “The data [in the new paper] look robust. Now we will need to spend several years brainstorming explanations. It’s fine to consider the possibility that phosphine is a signature of life on Venus, but there will be other explanations as well.”

Figuring out whether life is the source of Venusian phosphine, or whether it came from some other source, will take more data and better modeling of the planet’s behavior. Venus has now become one of the closest spots in the universe to investigate whether life exists beyond our own planet. Alas, Venus is woefully unexplored compared to some of our other stellar neighbors. A mission to send a probe plunging through the atmosphere of Venus and sample the cloud’s chemistry is currently in the works.