Earlier this year, Breakout Labs, the subsidiary organization created by PayPal co-and billionaire-investor Peter Thiel, announced a few select biotechnology startups that would receiving funding to further their ideas. Breakout Labs’ mission is to invest in companies that are looking to make “radical scientific advances” mainstream, essentially boosting the best underfunded inventions to the tune of up to $350,000 (plus consultation help from Breakout Labs).

Well, Breakout Labs is at again, announcing funding ventures for the second time this year. This time, the ideas range from adhesives that mimic the skin of geckos, low-cost sensors that can tell if food has gone bad, metals that repel water, and a mission to fight aging. The overarching trend in this announcement is funding advances in microstructure: three companies use mechanical innovation on a nanoscale to seemingly change the property of the material.

Here’s more about the next projects that could change the world.

NanoGriptech

Geckos can climb almost any surface, scuttling up walls and across ceilings with relative ease—this is because their feet are covered in microscopic hairs that grip onto porous materials. NanoGriptech is using this idea to build materials that grip without leaving sticky adhesives that leave residue. They call this dry adhesive Setex, which is repeatable and pressure-sensitive. Under a microscope, Setex looks like a uniform field of mushroom-shaped suction cups. The cups grab onto surfaces and can stretch up to 700 percent of their original length to remain attached to a surface. They’re fabricated from polyurethane.

NanoGriptech sees applications for Setex across fields like computer and furniture manufacturing, medicine, and robotics. The Pittsburgh-based company even released a video showing a robot with Setex fingertips delicately (for a robot) turning the pages of a book.

C2Sense

The era of the sniff-test might be soon over, thanks to Cambridge-based C2Sense. The technology, developed at MIT’s Swager lab, uses carbon nanotubes to tell you when your food has gone bad. Basically, the sensor is a bunch of very sensitive carbon nanotubes between two electrodes. When the nanotubes come into contact with specific substances in the air, like mold, they stick to the nanotubes and the electrical current changes. C2Sense says they can fit 30 sensors into the size of a credit card.

The sensors are incredibly low-energy, using only 0.00001 Watt, and C2Sense says they can detect ethylene, amines, and other gases expelled by rotting food at even sub-parts per million concentrations.

CyteGen

Google’s Calico Lab made headlines in 2013, when the company announced it was going to “cure death.” Now, Thiel is investing in a similar mission. CyteGen tackles aging from the perspective that aging is a holistic process, not specific deterioration of body parts.

“There is an assumption that aging necessarily brings the kind of physical and mental decline that results in Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and other diseases. Evidence indicates otherwise, which is what spurred us to launch CyteGen,” said George Ugras, co-founder and president of CyteGen.

While CyteGen has held their cards close in regards to technique, the team members from eight universities will focus on neurodegenerative diseases. The name, CyteGen, is a close parallel to the field of cytogenetics, which looks at chromosomal structure in individual cells.

Maxterial Inc.

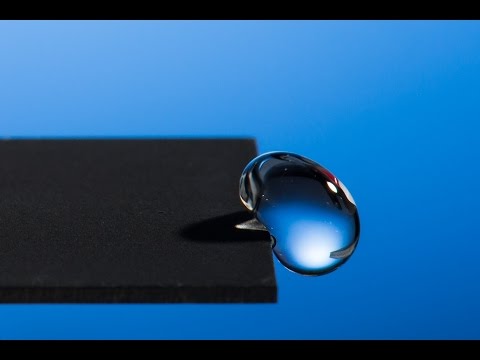

The modern world is built with metal: steel girders serve as the backbone to our skyscrapers, and bridges would not serve as long or stretch as wide if not for metal piers and piles. An inherent problem in exposed metal, however, is rust. Maxterial Inc., by re-engineering the outer layer of metal, has actually caused the material to repel liquids. Materials with this property are called hydrophobic, although the most common way to make something hydrophobic now is to spray it with a water-repellent coating.

Maxterial designed their outer coating to have tiny air pockets, reducing the surface area so water can’t latch on. They think this technology could reduce ice formation and corrosion on structures. They might not be the only researchers with this idea: A similar concept developed by the University of Rochester and released in January details a laser-etched surface that repels water in a similar way, though the Rochester team created a surface with the opposite effect—water crawled up against gravity. A demo video shows their water-repellent technology in use for a cooking pan, to which moisture doesn’t stick.

Breakthrough Labs points out to us that Maxterial published information about its technology two years before the research at University of Rochester, however, and that the company can produce on a large scale more sustainably and affordably than competitors. We’ll see how those claims pan out once the technology is more widely available.

The next round of funding

Breakout Labs has already funded 26 companies, and they’re constantly looking for more. You can submit an inquiry via their online form, and if they are interested in a full application, you must provide one in 30 days. The full application requires a scientific abstract, mission statement, biographic summary, and the full disclosure of other outside financial support.

Updated to include further information on Maxterial provided by Breakthrough Labs