More than 60 years after the first known case of human HIV infection, and 40 years after the beginning of the deadly HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States, a vaccine could be on the horizon.

In a Phase I Clinical trial that began in 2018, scientists at the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) and Scripps Research gave 48 participants two doses of either the vaccine candidate or a placebo, spaced two months apart. Results show that, in 97 percent of recipients, the vaccine stimulated the immune system to produce immunoglobulin G (IgG) B cells—a first step to making rare but powerful antibodies required to protect against various strains of HIV.

Now, IAVI and Scripps Research have announced they will continue building on the success of that first study by partnering with Moderna—the producers of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine—to apply their mRNA-based technology to speed up the HIV vaccine’s development.

[Related: How does an mRNA vaccine work?]

HIV has infected approximately 75.7 million people globally since the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, and killed 32.7 million. Though deaths are much lower now (roughly 38 million people are currently living with HIV), the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 1.2 million Americans live with HIV today, and UNAIDS estimates that around 690,000 people died from AIDS-related illnesses in 2019.

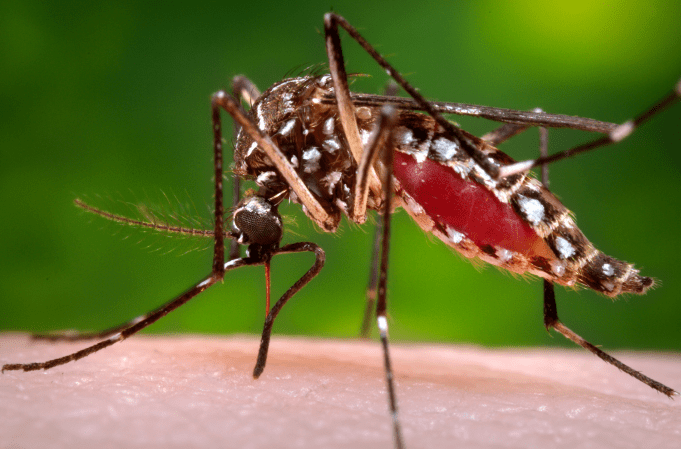

Developing a vaccine for HIV has been a huge challenge. The virus replicates in less than 24 hours and mutates at a rapid rate. But its deadliest quality is the fact that HIV directly targets the immune system, taking out the very cells that usually act as the body’s main line of defense.

This new potential vaccine works by stimulating the immune system to produce IgG B cells, which can then go on to produce what are called “broadly neutralizing antibodies,” or bnAbs. These are specialized blood proteins that scientists first found in AIDS survivors in 1990. These bnAbs can attach to hard-to-access HIV “spikes” and disable the virus. If researchers can spur bnAb production in humans, it could lead to vaccines for other difficult-to-manage viruses, too.

News of this trial and its success has been a long time coming. In tweets and postings online, several people have pointed out that though mRNA vaccine technology has been in the works since the 1990s, it took COVID-19 to bring it to fruition. HIV vaccine research has been going on a decade longer, since the 1980s.

One viral tweet reads, “It’s certainly not lost on me, a queer person, that a global pandemic that affected ‘everyone’ spurred the development of an mRNA vaccine in *record time* and that that mRNA technology is now being used to develop a vaccine for AIDS nearly 40 years after that epidemic started.”

These results, though positive, are still very preliminary, so there’s much work to be done before a vaccine that prevents HIV is available. A working preventative vaccine against a disease that has taken so many lives—especially in marginalized communities—would be uplifting news. If an HIV vaccine does eventually come out, it could potentially save a great number of lives for years to come.

Correction April 12, 2021: This article previously stated that HIV has taken the lives of 75.7 million people globally. In fact, HIV has infected that many people, but has killed less than half of those infected.

Correction: This post has been updated to reflect the fact that the current preliminary trial showed that the treatment produced immunoglobulin G (IgG) B cells, not broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs). These IgG B cells would be the first step in a process that eventually produces bnAbs.