Last December, television reporter David Jones tweeted a time-lapse of an impenetrable cloud of snow overtaking Manhattan and swallowing it whole by the end of the 32-second clip.

“Run!” one person responded to the video, which has now been viewed about 350,000 times. “Produced by Stephen King,” another joked, joined by more than a few references to the Game of Thrones’ “Winter is coming” tagline.

About a minute before Jones posted the video, the National Weather Service inundated cellphones around the New York metro region with a rare emergency alert for a “Snow Squall Warning.” It was the second time New Yorkers received such a push alert, but the Northeast has long experienced the short-lived burst of heavy snowfall characteristic of a snow squall.

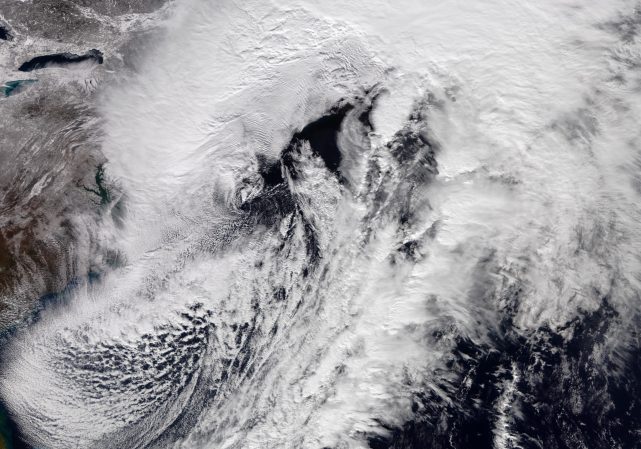

“We’re more used to precipitation in wide swaths: a field of snow or a shield of rain,” says University of Oklahoma meteorologist Jason Furtado. But during a squall, he says, “it goes from not really experiencing anything to a downpour of snow.”

To be clear: snow squalls are distinct from flurries or blizzards. Flurries happen when snow suddenly stops and starts. Sometimes they are so mild they don’t even leave evidence on the ground. Snowstorms are more enduring and intense. By definition, blizzards reduce visibility to a quarter-mile, feature winds of at least 35 miles per hour, and maintain those conditions for at least three hours. A snow squall is none of these things, says Brian Jackson, a meteorologist for the National Weather Service: “It’s a quick, heavy burst.”

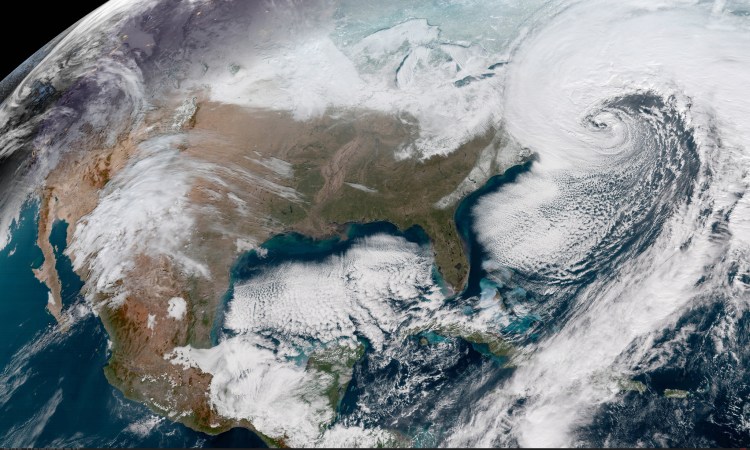

Squalls are the worst of both weather conditions. Unlike snowstorms, short-lived and quick-hitting snow squalls can travel up to 60 miles per hour and move in and out of an area in less than an hour. And unlike flurries, squalls can accumulate significant amounts of snow and are accompanied by seriously strong winds and occasional lightning, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (The word “squall,” by the way, refers to violent winds and probably comes from the Swedish skvala “to gush” or the Old Norse skvala “to cry out.”)

They’re not terribly uncommon. One NWS study of snow squalls in northern New York and Vermont identified at least 36 of these weather events over a 10-year period. Researchers found the median duration of heavy snow clocked in at 17 minutes, and that most occurred during daylight, with almost 70 percent of squalls falling somewhere between 1 p.m. and 11 p.m.

Some weather events, like tornadoes and halos, occur under very specific circumstances. But there are many ways to make a snow squall, Jackson says. For starters, they’re not necessarily a byproduct of major winter storms. Instead, snow squalls tend to form as narrow bands of heavy, wind-driven snow along or behind sharp cold fronts, according to the National Audubon’s Field Guide to Weather. Counterintuitively, warmer winters can actually lead to more snow squalls, says Ryan Stauffer, a research scientist at the University of Maryland and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. The same way a hot day can feed summertime thunderstorms, he says, a clear and sunny winter sky can provide an open path for snow squalls to travel farther and drop more snow.

A snow squall’s abrupt white-outs and temperature drops can be lethal, especially for drivers on interstates who have no reason to expect suddenly slick roads or heavy snowfall. “Snow squalls are probably the top of the list for most dangerous winter weather,” Stauffer says. “They’re small in scale, but very intense.” Snow squalls regularly lead to deadly highway pileups, which is one of the reasons NOAA decided in 2018 to add the phenomenon to its nationwide shortlist of weather events that qualify for an emergency alert. (This is why, last December, so many New Yorkers heard of snow squalls for the first time through push alerts on their phones.)

“It’s instantaneous—like a flash flood or severe thunderstorm warning,” Jackson, of the National Weather Service, says of snow squalls. “There’s no lead time,” he says, except “now we provide an alert.”

The NWS suggests that drivers who receive a snow squall alert or start to notice these conditions should slow down, turn on their headlights, and avoid slamming on their brakes—or better yet, pull over (if it can be done safely) or delay travel until the squalls fizzle out. “They can drop a lot of snow, very fast,” Furtado says, “but they don’t tend to last for very long.”

One historical record claims a surprising upside to a snow squall: On April 27, 1932, a Mr. Alpers, of Westfield, New Jersey, reported seeing a rainbow during one. Rainbows can be visible after large amounts of precipitation, including snowfall. In fact, according to Jackson, a snow squall is perhaps the most likely snowy event after which you might catch that signature streak of colors. Because squalls pass through an area so quickly, it could be possible to witness one during the bookends of a squall, when some sunlight is still streaming, Jackson says. But spotting one in the midst of a squall’s whiteout, Stauffer says, is probably apocryphal.