To mark our 150th year, we’re revisiting the Popular Science stories (both hits and misses) that helped define scientific progress, understanding, and innovation—with an added hint of modern context. Explore the entire From the Archives series and check out all our anniversary coverage here.

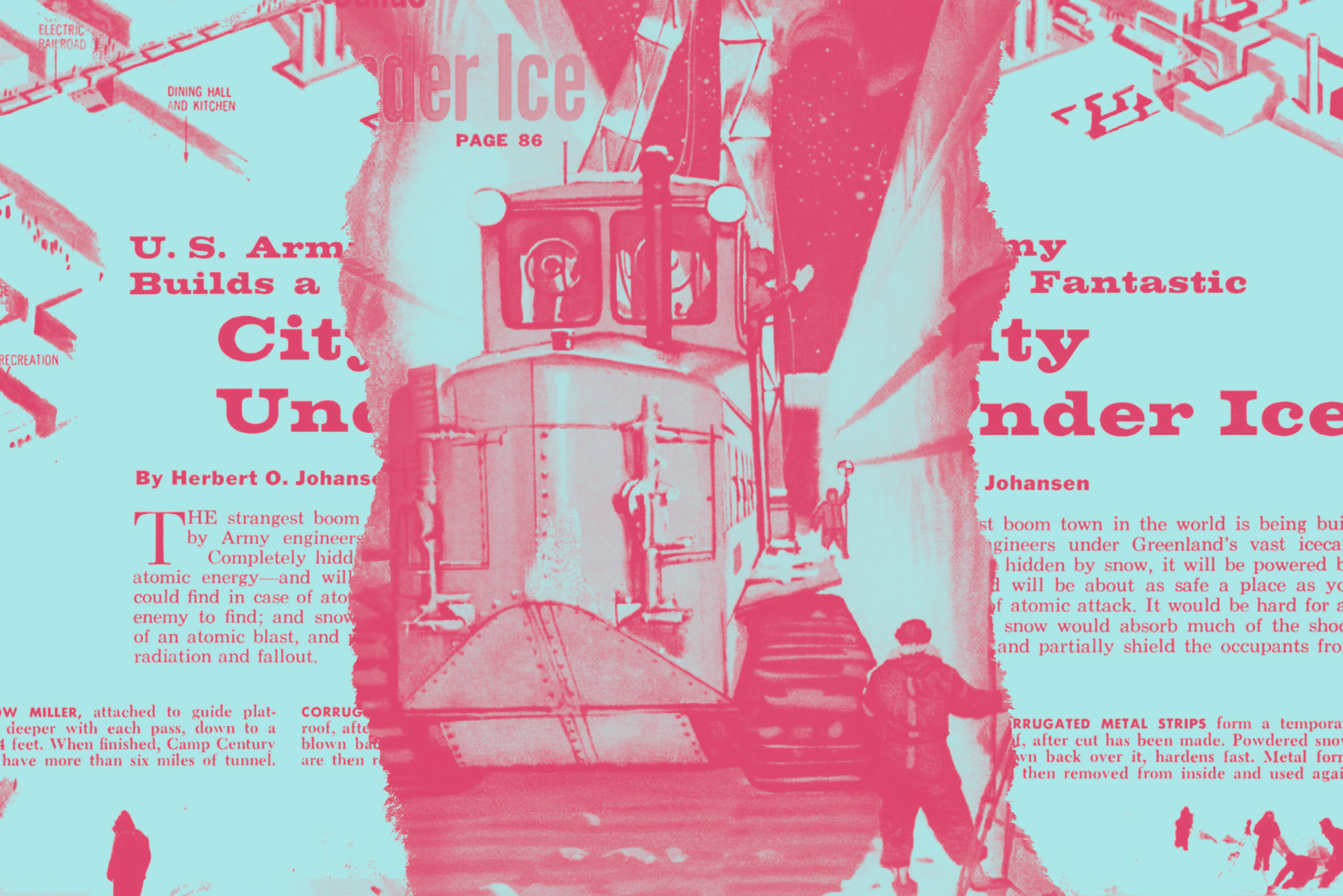

The 45-year Cold War probably never got colder than when the US Army decided to build Camp Century, a facility more than 30 feet below Greenland’s ice sheet. Herbert O. Johansen’s February 1960 Popular Science feature, “US Army Builds a Fantastic City Under Ice,” describes the Army’s unusual project, which turned out to have hidden Cold War ambitions.

The US Army Corps of Engineers began work on the camp in 1959, claiming it as a site to conduct polar research. While it’s true that the team drilled the first—and one of the most geologically revealing—ice cores ever to study climate change, the camp’s location was suspiciously close to Russia.

Johansen acknowledges that Camp Century was “about as safe a place as you could find in case of an atomic attack,” and that it “would be hard for an enemy to find.” But the story only mentions, in passing, that the site might be handy for the military. He otherwise steers clear of the usual Cold War themes (Popular Science ran many such stories throughout the 19th century) to focus on the camp’s luxurious subglacial living conditions, with “spacious dormitories,” “hot and cold showers,” and “a laundry and a barber shop.”

By 1967, the military abandoned Camp Century. In 1997, the Danish Institute of International Affairs released reports about Camp Century’s undisclosed military goals. Codenamed “Iceworm,” the US Army’s original plans included expanding the facility to 52,000 square miles of ice tunnels capable of deploying nuclear missiles. Even if the Danish government had approved the plan (it did not), the Greenland glacier refused to cooperate. As Johansen reported, “one thing the engineers haven’t been able to lick is the slow, plastic movement of the ice, which causes the walls to close in and the corridors to twist.” Now, climate change threatens to expose the site’s nuclear and other hazardous waste, which were supposed to remain ice-entombed forever. Perhaps, the early thaw will uncover other unsavory truths?

“U.S. Army builds a fantastic city under ice” (Herbert O. Johansen, February 1960)

The strangest boom town in the world is being built by Army engineers under Greenland’s vast icecap. Completely hidden by snow, it will be powered by atomic energy—-and will be about as safe a place as you could find in case of atomic attack. It would be hard for an enemy to find; and snow would absorb much of the shock of an atomic blast, and partially shield the occupants from radiation and fallout.

In building the fantastic community, 800 miles from the North Pole, Army Engineers, in cooperation with the Danish Government (Greenland is a part of the Kingdom of Denmark), have proved that the traditionally antagonistic Arctic can be tamed.

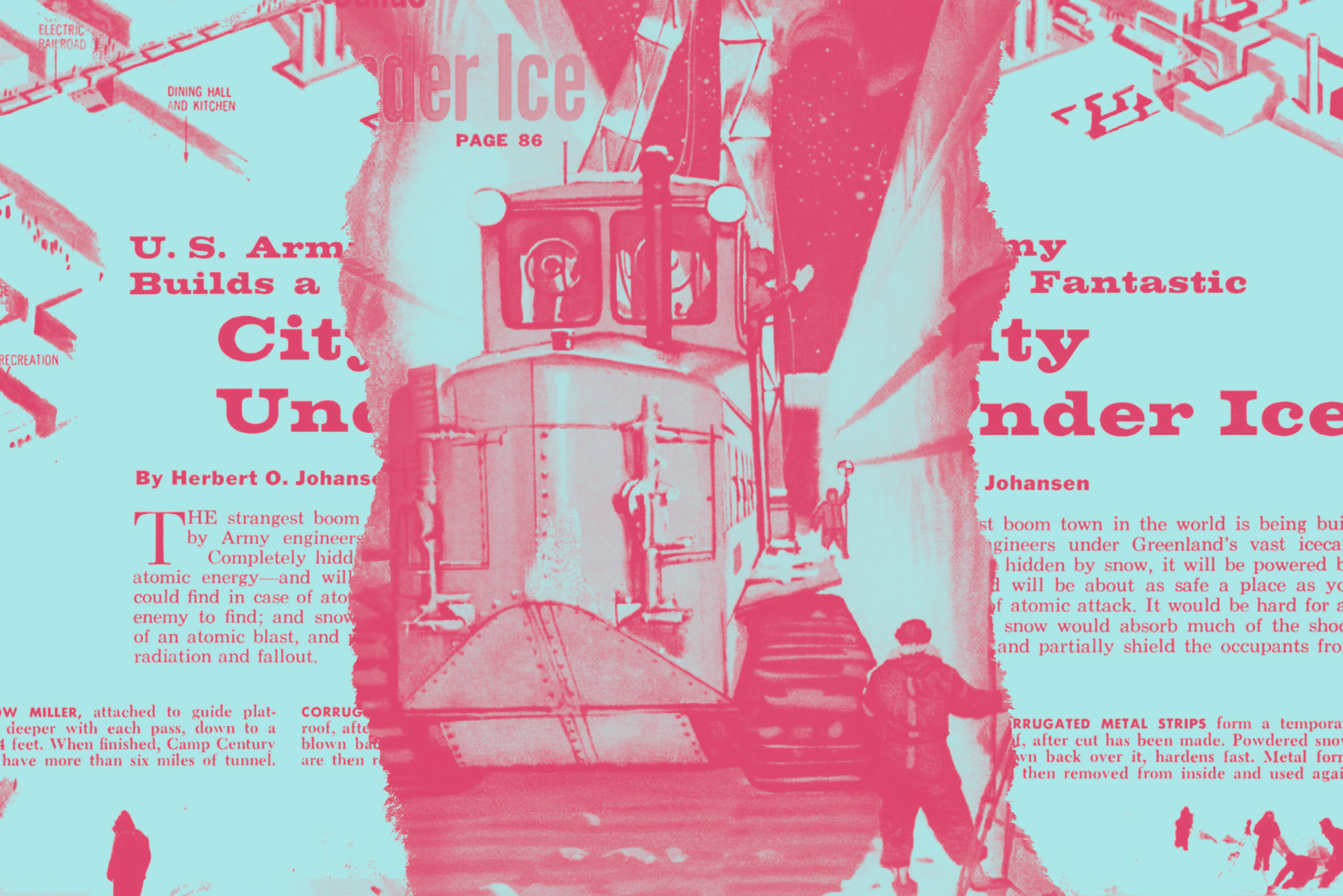

An electric railroad running through a tunnel cut in the snow will connect the town with the supply base at Thule Air Base 152 miles to the west. For air supply there will be landing strips of compacted snow for the largest cargo planes, and landing pads for helicopters.

It will be home—snug, comfortable, and warm—for 100 scientists, engineers, and soldiers who are expected to move in late this year. After a hard day’s work they will be able to relax with tall drinks cooled by deep-dug ice that was formed long before Columbus discovered America.

It is Camp Century—a year-round haven for the men who will study problems of living, working, or fighting in one of the world’s harshest environments, where winter temperatures drop to 70 below zero and winds whirl snow in a blinding fury at 100 miles an hour. With previous shelters, the open season was limited to five months—May through September.

Now the men will live and work in a series of insulated prefabricated buildings connected by snow corridors. Cumbersome Arctic clothing—parkas, bulky mittens, mukluks, scratchy woollies—won’t be needed even in the work areas, where the temperature will be kept at 40 degrees. It will be upped to 60 degrees in living quarters. A ventilation system will exhaust warm air from the tunnels to keep the snow walls at 20 degrees or below so they won’t melt. To prevent the snow floor from becoming slush, the buildings will be raised slightly to permit a circulation of cold air underneath.

Life in Camp Century

The inhabitants will never see daylight unless they venture outside. But during the worst months of the year—December and January— that won’t matter: The sun never rises.

At first glance the unnatural life within the confines of a buried snow town four blocks long, and three blocks wide looks forbidding, depressing, killing in its monotony. It would be if a man didn’t keep busy and have cheerful surroundings, and facilities for recreation.

Here the residents of Camp Century will score on all points. They will be busy at their jobs—from cooking to researching—eight to 10 hours a day. After that it’s up to a man’s individual taste. There will be a recreation hall and game rooms, a gymnasium, a hobby shop. A library will share quarters with a Base Exchange.

Movies will be shown every night. Television programs will come from the military TV station at Thule. Radios will tune in perfectly on Radio Moscow across the Arctic. Eating will be in a clublike dining room. Food will be the best (with an extra half ration to compensate for faster-burned-up calories) and steak will be in plentiful supply.

Spacious dormitories will replace double-down, zip-up sleeping bags; hot and cold showers the occasional lick-and-promise basin bath. A laundry and a barber shop will keep the outer man clean and neat; a 10-bed hospital with an operating room, the inner man in repair. A chaplain and chapel will serve spiritual needs.

Only one comfort of man—beyond the scope of the Army—will be lacking. It is hoped that fast air mail, ham radiotelephone chats with wife and family in the United States, and rotating four-month tours of duty will make icecap isolation seem less far away from home.

Some problems solved

Camp Centur —so named because its original site was 100 miles out on the icecap—is being built by the Army Corps of Engineers after five years of preliminary construction experiments on the Greenland icecap. Its research programs will be directed by the Army’s Chief of Research and Development. The working areas will be dominated by scientific laboratories, but should the need come for a similar military installation—perhaps an under-ice launching site for intercontinental ballistic missiles or interceptors—we have the blueprints, the techniques, the machines. At Camp Century, the Engineers have proved that they can:

- Make efficient use of construction materials at hand—snow and ice.

- Dig cut-and-cover trenching with an adaptation of Peter Snow Millers—huge rotary snow plows that for years have been keeping passes in the Swiss Alps open during winters.

- Adapt mechanical coal-mining machines to carve caverns into ice-hard snow to make expanded quarters, as well as space for storage and food refrigeration.

- Solve the water-supply problem, always serious in the Arctic, by drilling wells 150-feet deep, shooting down jets of steam, and pumping out water.

- Utilize an air-transportable nuclear power plant, with a capacity of 2,000 kw., to furnish light, heat, and power. A core of U-235 weighing less than 50 pounds will produce a year’s supply of electricity—doing the work of 35,000 barrels of fuel oil.

One thing the engineers haven’t been able to lick is the slow, plastic movement of the ice, which causes the walls to close in and the corridors to twist. With periodic shaving of the ice, they expect the camp to last about 10 years. Then it will be completely reconditioned.

The machines used for this maintenance also will carve out new and bigger storage vaults. Equipment and tools stored in them don’t rust, and food keeps indefinitely. With the techniques developed to build Camp Century, the engineers say they could hack out great ice caves to store surplus crops for use by future generations in times of famine.

Why a Camp Century?

The Greenland icecap, with a big, permanent supply base at Thule, is the ideal laboratory for studying snow and ice. Aside from weather implications, these are two elements we will be living with more and more. The entire Distant Early Warning radar network (DEW line) lies above the Arctic Circle—from the Kuriles at the western tip of Alaska, across Canada and Greenland. Lessons learned in the North Polar areas can be applied in the Antarctic, now increasingly important.

Greenland, with 708,000 square miles of icecap, two miles deep at its crest, is the birthplace of weather for much of the Northern Hemisphere. By drilling and bringing up core samples of ice formed through the ages, scientists can study the history of snowfalls and get information on the movement of air masses covering thousands of years.

“This information,” says Dr. Henri Bader, chief scientist of the Army’s Snow, Ice, and Permafrost Establishment, “will enable us to make fairly accurate predictions on future weather cycles.”

Air samples from the past, preserved as bubbles, are trapped in these ice samples. One Camp Century project is to try to determine how much air pollution has increased since the Industrial Revolution of the 18th Century introduced man-made smog. Ice cores from a depth of 160 feet contained volcanic dust from the great Krakatoa eruption of 1883 in the Dutch East Indies. And in the threefoot layers of snow that are deposited on the icecap each year, there is a permanent annual record of atomic fallout since Hiroshima.

This year-by-year accumulation of snow-become-ice is easily identified and accurately dated, somewhat as rings tell the age of a tree.

Samples of ice formed from snow that fell when Eric the Red set foot in Greenland in the year 982 already have been studied by scientists. With new thermal drilling equipment that will be used at Camp Century, they hope to go down 10,000 feet. The ice they then bring up will date back beyond the dawn of history—to the days when the footprints of Stone Age man were fresh upon the earth.

Some text has been edited to match contemporary standards and style.