This story originally featured on Outdoor Life.

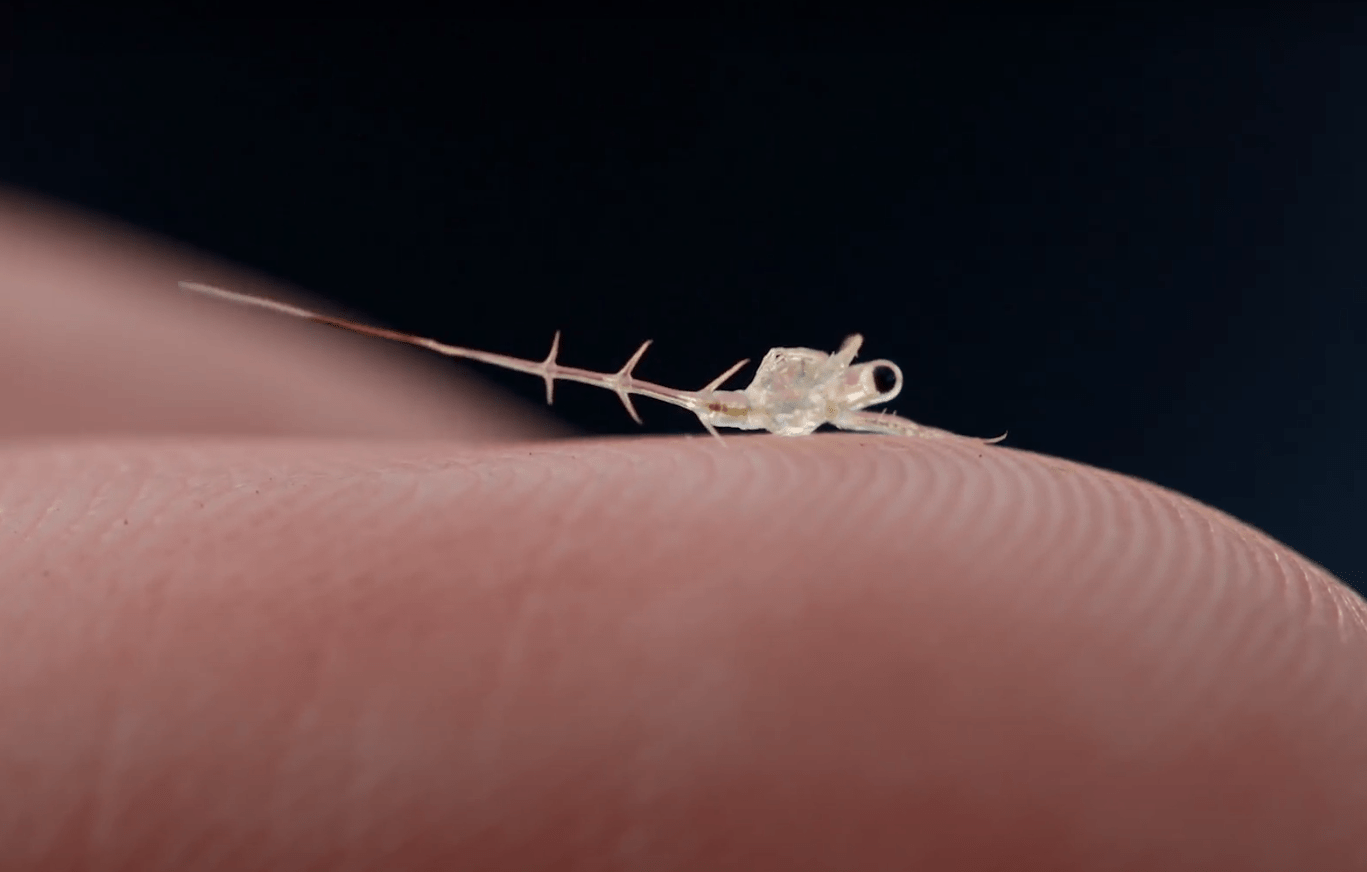

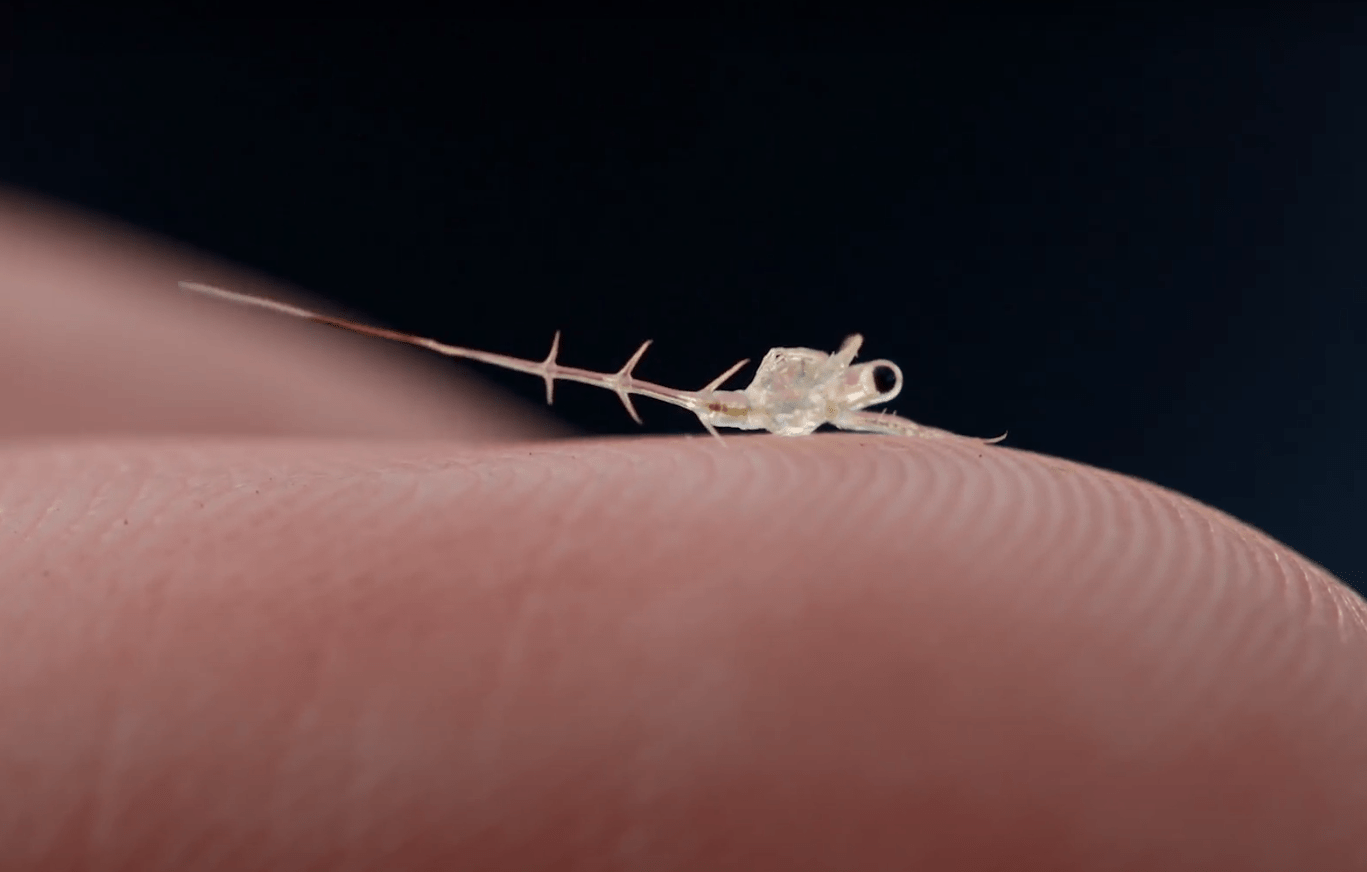

It seems that the next troublesome invasive species in the Upper Midwest is a tiny one. The spiny water flea has been latching onto fishing equipment, traveling the Great Lakes for decades, but now they are being transported to some of the most pristine waters in the Upper Midwest. The spiny water flea is about half an inch long. It’s a creepy little critter, with a single, distinctive black eyespot at the head of one to four spines. A barbed tail juts out of its backside, making up about 70 percent of its length. The translucent hitchhiker hooks onto watercraft, fishing lines—essentially everything and anything that touches the water—and then gets transported to new waters.

“Most water fleas eat algae, but a few of them, like spiny water fleas, also eat other water fleas. It’s kind of like wolves eating coyotes or foxes,” says Valerie Brady, an aquatic ecologist at the University of Minnesota.

While they present no danger to humans or domestic animals, spiny water fleas rattle ecosystems that support game fish. Spiny water fleas feed on other smaller, native water fleas, which are a vital food sources for small fish and keep algae in check. When plankton populations crash, that sinks small fish numbers, which in turn decreases game fish numbers.

“It’s not just another addition to the food web, it disrupts the food web and makes it harder for small or young fish to feed. That has potential implications for the whole food web,” Brady says.

The spiny water flea is being studied and monitored in Ontario’s Quetico Provincial Park and Minnesota’s Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. As more new anglers and boaters hit the water last year during COVID—and could be back out this spring—it’s even more critical to get the word out about this invader.

Like most damaging invasive species, spiny water fleas reproduce rapidly. At optimum temperatures, one female can produce 10 genetic replicas every two weeks.

Currently, there are no successful means to eradicate the species. With no natural predators, there’s no stopping water fleas once they land in a lake. Small fish will choke or puncture their organs if they try to consume the flea due to its long, sharp spine.

Spiny water fleas also bring a million-dollar public recreation problem. As the fleas feed on plankton that consume algae, algae blooms begin to sprout up across a lake. Water treatment costs stack up, with municipalities spending millions to return to clearer water, including Wisconsin’s Lake Mendota.

“Two to four million was the estimate of water treatment costs to get the same level of water quality that [Lake Mendota] had before spending water fleas,” says Tim Campbell, aquatic invasive species outreach specialist at the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute.

Where did the flea come from?

The spiny water flea was first identified in North American in 1984 in Lake Huron. Native to Russia’s Lake Ladoga, adjacent to the Baltic Sea, it arrived in the Midwest in the early 1980s after ships from European ports discharged ballast water into the St. Laurence River.

In the quarter-century since, the aquatic hitchhikers have spread by the “billions” across all of the Great Lakes. The creatures have begun to invade “our most pristine lakes,” the smaller inland waters of the Midwest and Canada.

“Once they get in, you can’t get rid of them. There’s no way to kill them without killing everything in the lake. That’s why we’re focusing so hard on stopping their spread,” Brady says.

Ecologists are calling on anglers and recreators to halt their spread. The most important step is to completely dry all fishing and boating equipment. The microscopic fleas can cling to fishing lines and survive in lake water at the base of your boat. Running a cloth down your fishing line can eliminate any aquatic hitchhikers reeled in.

“They cannot survive drying, so we urge anglers to get everything completely dry. The guidance is five days between boating trips [to different bodies of water], so if you [boat in spiny flea infested water] on Sunday, wait until the following weekend to go to a different body of water,” Campbell says.

Some have suggested that ducks are the culprits of cross-water spreads, but humans transporting the fleas is the clear issue. If you map out their spread, Brady notes, the majority of the fleas are found in lakes with public access.