What’s the weirdest thing you learned this week? Well, whatever it is, we promise you’ll have an even weirder answer if you listen to PopSci’s hit podcast. The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week hits Apple, Anchor, and everywhere else you listen to podcasts every-other Wednesday morning. It’s your new favorite source for the strangest science-adjacent facts, figures, and Wikipedia spirals the editors of Popular Science can muster. If you like the stories in this post, we guarantee you’ll love the show.

FACT: Scientists and high-society ladies once used radiation to grow mutant flowers and veggies

By Rachel Feltman

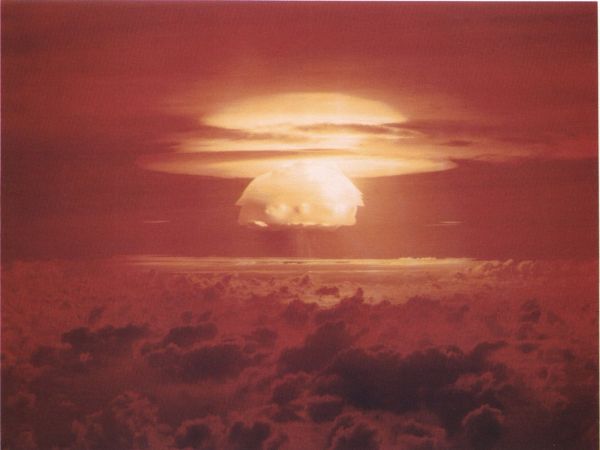

Most folks know that during World War II, the Manhattan Project figured out how to harness nuclear chain reactions to commit unspeakably horrifying acts of mass-murder and war. But in the early 1900s, when we were just starting to understand radioactivity, nuclear science had a much more fantastical and optimistic following. This led to plenty of dangerous and misguided nonsense, like irradiated slippers designed to glow in the dark, but also a general sense that understanding physics would give us unlimited energy and unlimited food—that it could make resources so abundant that utopia simply had to follow. Part of that research involved using x-rays to try to induce helpful mutations in plants like peanuts. Radiation can break down the bonds that keep DNA together, causing cancers when cells start reproducing out of control or radiation burns when they start dying. But DNA damage in sex cells can also get passed on to offspring, and result in literally any kind of physiological change.

All those rosy utopian avenues for using nuclear physics were put on hold so the US could make a terrible bomb, which we did. But the Manhattan Project did keep at least half an eye on radioactive plants. They understood that radioactive fallout was going to fundamentally alter the ecosystem of any place where bombs were tested or dropped.

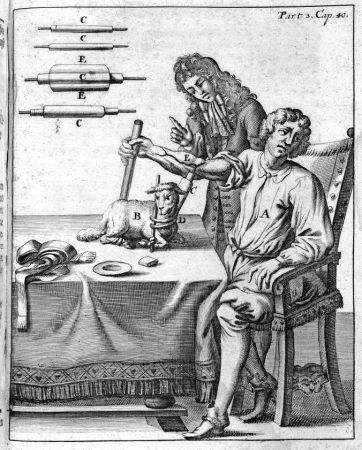

Enter gamma ray gardens, where scientists would essentially plunk a tube of radioactive material (usually the isotope cobalt-60) into the center of a field. They’d plant various crops in a kind of pizza pie configuration of concentric circles. Eventually the isotope rod would get dropped into a bunker that shielded the surface from its gamma rays, and scientists could safely go check on their spoils.

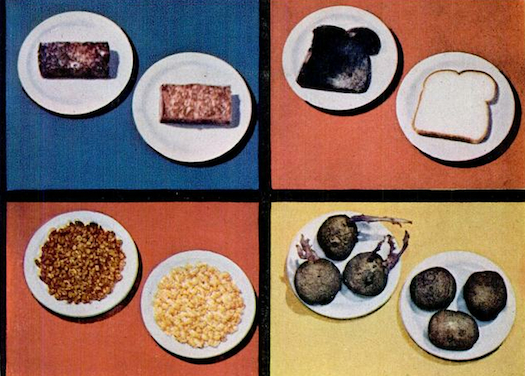

Gamma rays have an even smaller wavelength than x-rays—they’re something you can only get after you split into an atom—and they can shoot through basically anything like a bullet. So, surprise surprise, the plants right next to the radiation center would die. Some of the closest ones to survive would grow tumors. But somewhere farther out in the circle, you’d start to see plants that were just…a little different than what you’d planted. Maybe they’d grow especially tall, or have especially high fruit yields, or produce an unusual variety of colors in each flower.

That became very interesting to the US government during the cold war; politicians wanted to prove to the world that there was a bright side to the whole nuclear weapon thing. There were a bunch of initiatives designed to get nuclear physics into our everyday lives in a helpful and morally palatable fashion, and one of them was using those gamma gardens to create exciting and useful new plant varietals.

Researchers would start by trying to spot any potentially useful adaptations that cropped up thanks to irradiation. Then they’d take the mutant plant and try to improve on it; they might cross-breed with something else, or irradiate a second or third or fourth generation of it, for example. At each stage they would store some seeds, so that when they found something really neat—either for aesthetic or agricultural purposes—they could get those nuclear plants out to the public.

Even folks without any interest in nuclear science interacted with some of these plants, and we still do today. The Rio Star grapefruit, which is now very common, is just one example, which was bred in an atomic garden to have very dark flesh and sweet juice. Most of the world’s mint oil comes from a peppermint cultivar called “Todd’s Mitcham,” which is resistant to certain fungi, and was bred at Brookhaven National Lab’s gamma garden. There are more than 3,000 registered plants that got to be the way they are because of radiation.

But some civilians wanted to get an even closer look at this exciting new science. One of the most famous was an oral surgeon named CJ Speas, who shot seeds up with radiation in a backyard bunker and sold them across the world. This provided a hint of the same mystery of a gamma garden without having to bury cobalt-60 in your own backyard; you never knew what kind of mutation the seed might have taken on until you planted it.

One of Speas’ most prolific overseas distributors was a British woman named Muriel Howorth. She also started the Atomic Gardening Society, which did things like put on interpretive dance performances to explain how nuclear physics worked.

Some countries still use gamma gardens to find new and better plant varietals, but more targeted genetic engineering has made the practice pretty obsolete. While post-war proponents talked about irradiation as if it jump-started the process of evolution, it actually only jump starts the process of mutation. For more info on this strange era of botany, listen to this week’s episode of Weirdest Thing!

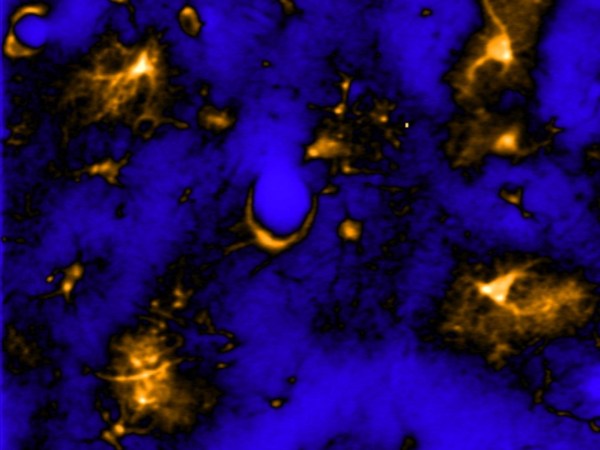

FACT: Pain is subjective—but that doesn’t make it any less painful

By Leigh Cowart

Every time you experience pain, the brain cooks it up fresh, which sometimes means mistaking a snake bite for a pointy stick. Pain is, simply and maddeningly, always subjective. There’s no machine in existence today that could peer inside your head and quantify the exact amount of pain you’re in. There’s just no standard experience of pain! When you have pain, the brain takes into account your surroundings, emotional state, expectation, arousal, and a slew of other factors to calibrate and deliver the aversive sensation we know so well. But this doesn’t mean pain isn’t real, quite the contrary: the experience of pain is as real as the brains that provide the suffering itself. And I would know. Even my scientific understanding of the trickster capsaicin could not save me from sobbing through the exquisite burn of Dante’s gazpacho when I ate the world’s hottest pepper. For more agony in the name of science, tune into this edition of The Weirdest Thing and check out my book, “Hurts So Good: The Science and Culture of Pain on Purpose.“

FACT: Puppies get emo, too

By Sara Kiley Watson

Ever wonder why your seemingly perfect pup turned into a total menace over night right before their first birthdays? It might just be teen angst.

Until fairly recently, there’s not been a whole lot of proof that animals that aren’t human undergo the same kind of parental-mind-boggling teen drama during puberty. Especially when it comes to the animals that we really see as our own babies. That is, until a study came out in 2020 about teenage puppies going through shockingly similar dramatic changes in attitude—especially towards their parents. A team of British researchers worked with the charity Guide Dogs to see if around doggy puberty, around six to nine months, and substantial behavioral differences were spotted.

The team of researchers took two different groups of pups, all German shepherds, golden retrievers, labrador retrievers or crosses of these breeds. The first group was around five months old, still in their bouncy baby phase where their human parents are the light of their lives, much like kids before hormones start running amok. The second group was at eight months—peak of potentially grouchy teen angst era. They took these two teams of dogs and did the classic “sit” command. At five months, pups responded pretty well to their parents telling them to sit, and not so much a stranger. But by eight months, this reverses—a teenage pup will more gladly sit when some random person asks them to, but when it comes to mom or dad, they’ll be more angsty about it.

Considering, however, that we can’t really give up our teens for adoption when they are driving us up the wall, folks do have the ability to rehome their dogs if they start acting out of control—even if it is just their hormones making them a little grumpier than usual. So if your pup is acting out a little more than usual, remember how you were when you were going through puberty, because growing up can certainly be ruff for man’s best friend.

If you like The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week, please subscribe, rate, and review us on Apple Podcasts. You can also join in the weirdness in our Facebook group and bedeck yourself in Weirdo merchandise (including face masks!) from our Threadless shop.