What’s the weirdest thing you learned this week? Well, whatever it is, we promise you’ll have an even weirder answer if you listen to PopSci’s hit podcast. The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week hits Apple, Anchor, and everywhere else you listen to podcasts every-other Wednesday morning. It’s your new favorite source for the strangest science-adjacent facts, figures, and Wikipedia spirals the editors of Popular Science can muster. If you like the stories in this post, we guarantee you’ll love the show.

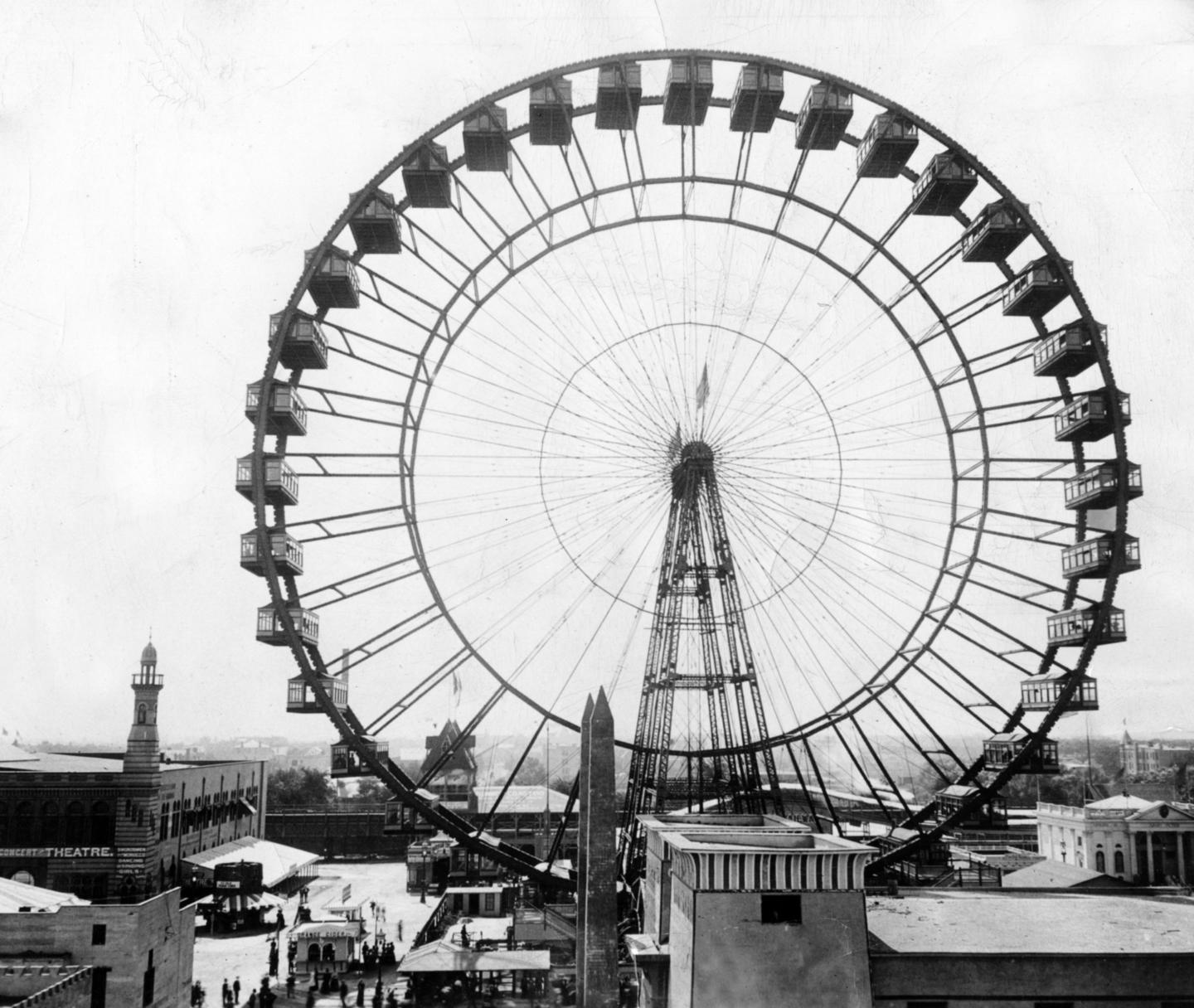

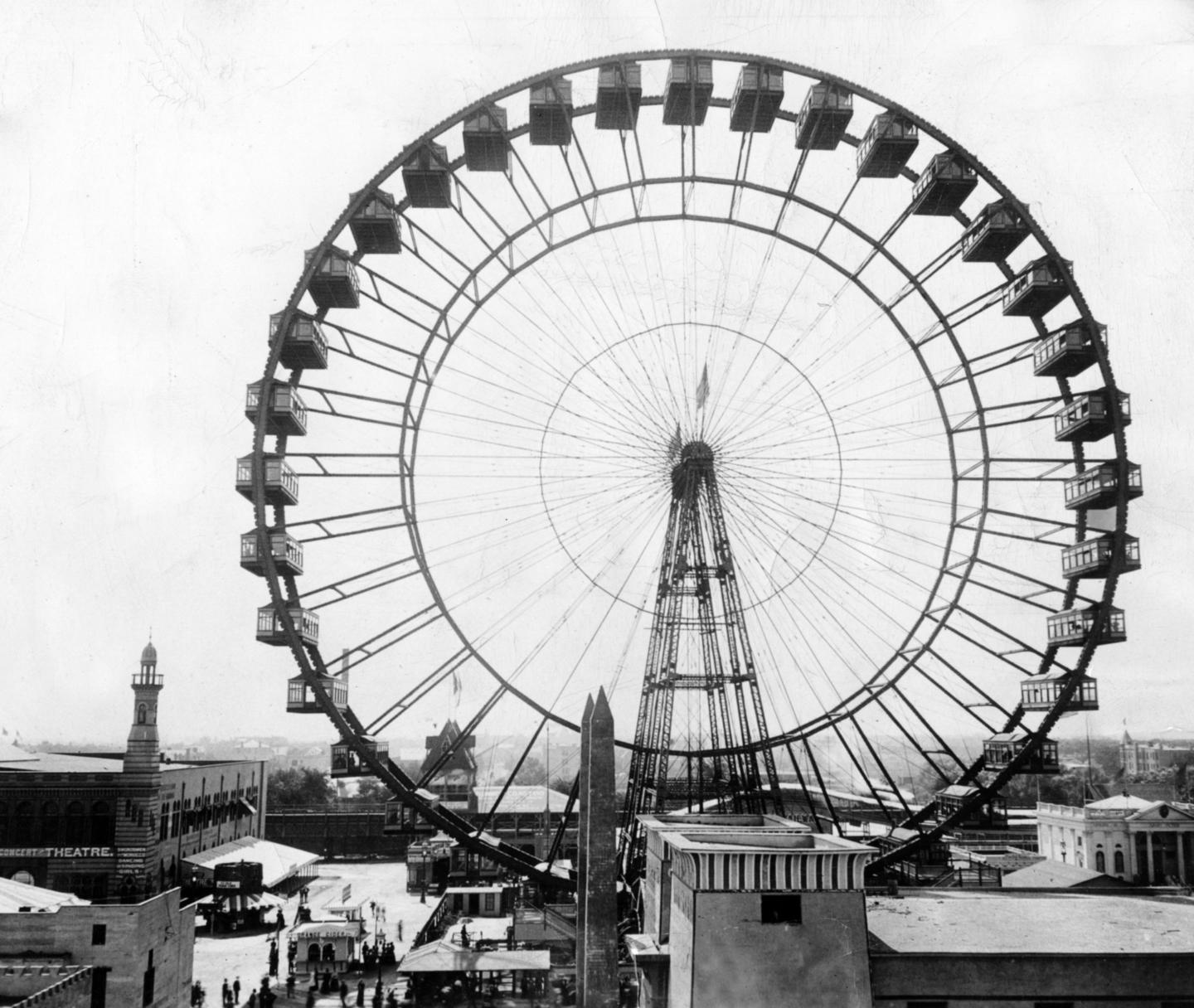

FACT: The Ferris Wheel has a shockingly sad (and short) origin story

By Rachel Feltman

The story of the world’s first and only Ferris Wheel starts as so many great stories do: With Americans desperately trying to outdo the French.

When Paris hosted the World’s Fair in 1889, entrepreneurs and engineers spent more than two years and about $1.5 million building a tower around 1,000 feet high—the Eiffel Tower, to be exact. It spent 41 years as the tallest man-made structure in the world, at which time it was just barely surpassed by the Chrysler Building in Manhattan.

So when Americans started prepping to host the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which opened in 1893, they were still smarting from France’s big success and needed a comparable spectacle.

Enter George Washington Gale Ferris Jr., born in Pennsylvania to the Galesburgh Gales. His family moved out to Nevada, but he wound up back in Pittsburgh and founded a company that tested and inspected the metals used on railroads and bridges. When a call went out for Exposition proposals in 1891, Ferris responded with a plan he said would “out-Eiffel Eiffel.” His concept? A very, very big wheel.

Now, Ferris did not invent the concept of putting people on a wheel and spinning them around. We know “pleasure wheels” existed as early as the 1600s in Europe and Asia, but these were small enough for people to crank by hand (and looked totally ridiculous).

According to many New Jersey publications, Ferris stole the idea for the modern wheel from William Somers, who put up three pleasure wheels in Atlantic City in the early 1890s. Ferris rode those wheels and definitely got his inspiration from Somers, but those attractions were only 50 feet high.

What Ferris wound up building—after spending some time convincing the World Fair committee it could be done, raising $400,000 for construction costs, and paying for the required safety tests himself—was a wheel 246 feet high. It was a feat of engineering in every sense of the word. When it was complete, it could hold more than 2,000 passengers at once for each 20-minute ride (which only included two rotations, but thrilled visitors nonetheless).

But Ferris didn’t live long enough to successfully brand the concept of a massive pleasure wheel, so the many iterations of his great invention weren’t truly his. Find out more about his tragic tale—and the explosive fate of his one true wheel—on this week’s episode of Weirdest Thing.

FACT: Animals of different species sometimes form friendships to hunt (and cuddle)

By Purbita Saha

Earlier this year, a video of a coyote and an American badger frolicking together in the Santa Cruz mountains stunned the internet. While Disney+ was presumably shopping the rights for a 10-part series about the pair, biologists pointed out that similar relationships have been documented many times in science, and for even longer in Navajo and Hopi storytelling.

But the friendship between the species isn’t just cute. It’s a tale of survival: In certain seasons and habitats, badgers and coyotes will tag team to trap squirrels, groundhogs, and other prey in their burrows. Between the badger’s digging power and the coyote’s quick feet, the two can crank up their hunting success rate by 9 percent. If all goes well, the partners might rendezvous multiple times—rounding out their feasts with some nuzzling to celebrate the end of a day’s hard work.

So, maybe it’s fair to say that the relationship isn’t just built on survival. Behavior ecologist Jennifer Campbell-Smith wrote an eye-opening reaction in High Country News that urges viewers to see collaborative hunting as an example of complex social behavior among animals. It’s something to consider—and study—in other surprising friendships in nature:

- Dolphins and whales blitz fish together. A 17-year-long study off the northeast coast of New Zealand found that pods of false killer whales and common bottlenose dolphins often mingle and forage together.

- Grouper recruit eels to prowl coral reefs. Swiss scientists snorkeling in the Red Sea observed the flabby fish leading morays to prey hiding out in nooks, sometimes using a “headstand” as a signal. The biologists think this is the first record of cooperative hunting in fish.

- Birds and humans team up to find treats in the forest. The Yao community in Mozambique follows greater honeyguides to giant, wild bee hives—and has likely been doing so for centuries. They’ve even created a specific rolling call that beckons the birds: brrr-hm.

FACT: You can totally hypnotize a chicken

By Jessica Boddy

The inspiration for this fact struck the last time I was home visiting family in the Chicago suburbs. We were reminiscing about the very first time our dog Zeke caught a possum. After marching around the yard with the beast in his mouth for quite some time, my dad finally caught him by the collar and made him drop his prey. The possum was apparently dead—frozen, stiff and drooling. Dad went inside to bring Zeke in and grab a shovel, but by the time he returned to dispose of the possum it had vanished. We thought it was dead, but it was just playing possum.

It turns out that “playing dead” is extremely useful in a survival situation, since a predator doesn’t usually want to eat something it hasn’t killed personally. It could be riddled with some disease. And it’s not just possums that take advantage of this instinct. The behavior is something called apparent death, and TONS of species use it as a defense mechanism—plenty of amphibians, iguanas, sharks, pigeons, chickens, butterflies, beetles, ants, bees, stick bugs… the list goes on.

Humans have found ways to induce this state in animals over the last few hundred years. And when they do that, they like to call it hypnosis. Adam Savage, Ernest Hemingway, Werner Herzog, and even Al Gore are all noted chicken hypnotizers. Like magic, the chickens just freeze solid for 30 minutes at a time (sometimes longer). How do the chicken hypnotists do it? Listen to this week’s episode to find out!

If you like The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week, please subscribe, rate, and review us on Apple Podcasts. You can also join in the weirdness in our Facebook group and bedeck yourself in Weirdo merchandise from our Threadless shop.