It might be time for the megalodon to move over and make room for a new ancient aquatic animal. There’s a newly discovered dinosaur species that may also be pretty good swimmer with duck-like diving abilities.

Natovenator polydontus was a theropod (a hollow-bodied dinosaur) that had three toes and claws on each limb. It lived about 145 to 66 million years ago in Mongolia, during the Upper Cretaceous period. Its recent discovery was outlined in a study published last week in the journal Communications Biology. The name Natovenator polydontus means “many-toothed swimming hunter.”

[Related: Were dinosaurs warm-blooded or cold-blooded? Maybe both.]

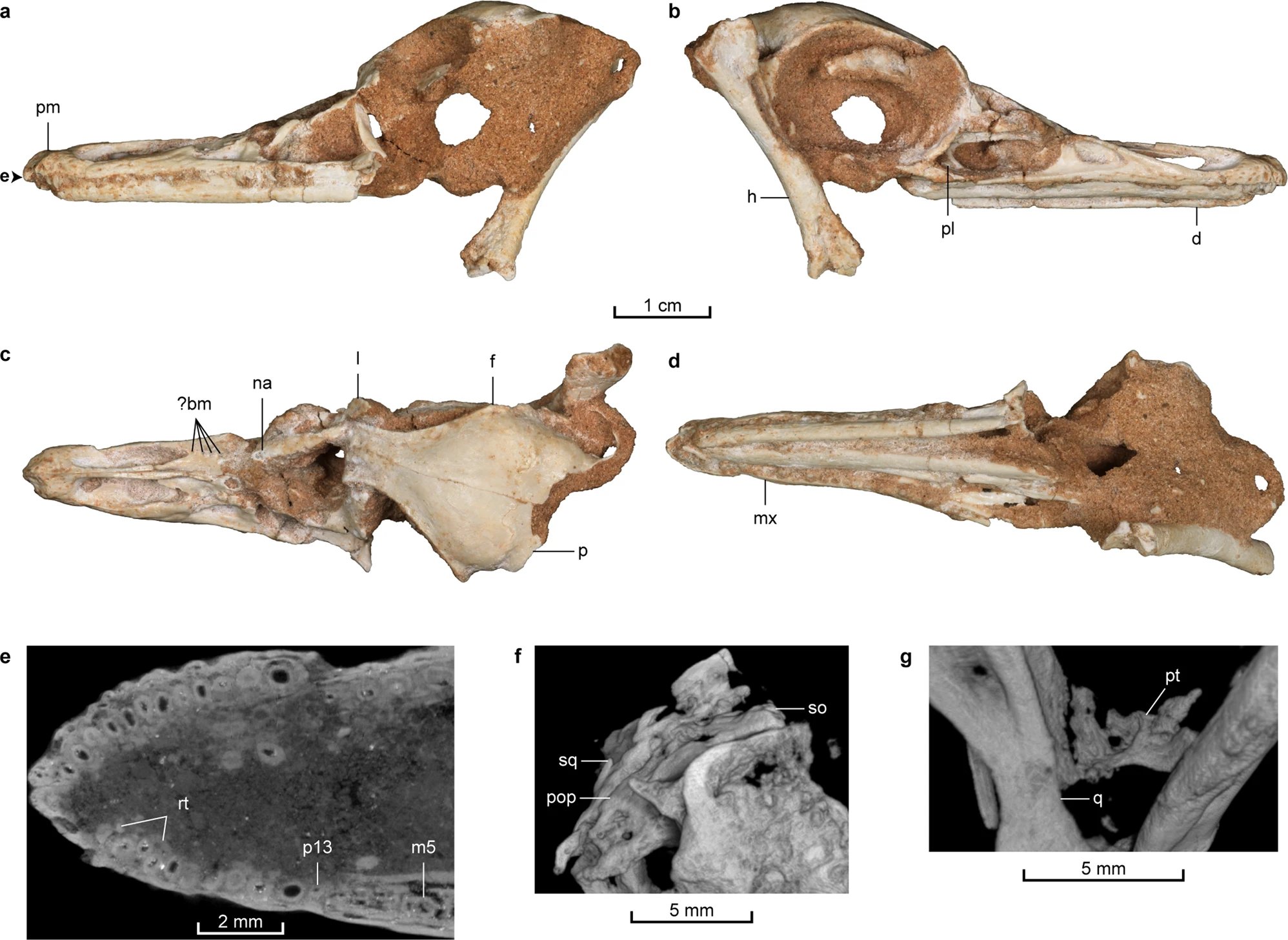

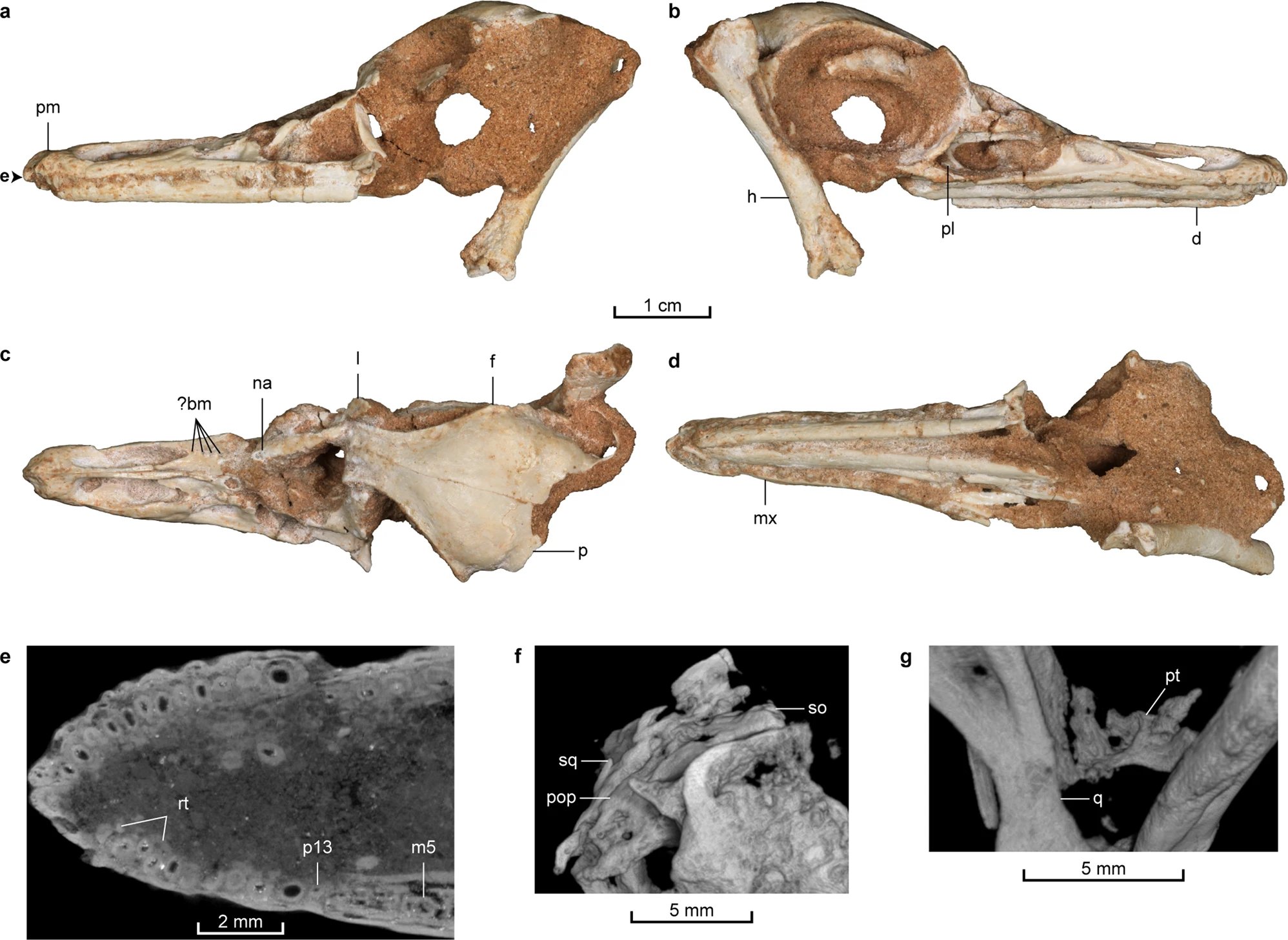

One of the similarities that Natovenator has with modern, diving birds is it’s streamlined ribs.

“Whereas diving birds are well known to have streamlined bodies, such body shapes have not been documented in non-avian dinosaurs,” wrote the authors in the study. “Its body shape suggests that Natovenator was a potentially capable swimming predator, and the streamlined body evolved independently in separate lineages of theropod dinosaurs.”

The specimen that the team from Seoul National University, the University of Alberta, and the Mongolian Academy of Sciences examined in this study is similar to Halszkaraptor, another dinosaur that was discovered in Mongolia. Scientists believe Halszkaraptor was likely semiaquatic, but the Natovenator specimen in the study is more complete than one of the Halszkaraptor. This makes it easier for scientists to see Natovenator’s streamlined body shape.

Natovenator is a cousin of the famous Velociraptor, but has a much more streamlined look, with its long jaws and tiny teeth. The specimen was discovered at a spot in the Gobi Desert called Hermiin Tsav or (Khermen Tsav), which is a hot spot for preserving multiple dinosaur species.

David Hone, a paleontologist and professor at Queen Mary University of London, told CNN that it is difficult to say exactly where the new species falls on the spectrum of totally land-dwelling animals to totally aquatic animals. However, the specimen’s arms, “look like they’d be quite good for moving water,” he said. Hone participated in the peer review for this study.

[Related: Spinosaurus bones hint that the spiny dinosaurs enjoyed water sports.]

According to Hone, the next steps to understand Natovenator’s motion should be modeling of the dinosaur’s body shape to help scientists understand exactly how it might have moved. “Is it paddling with its feet, a bit of a doggy-paddle? How fast could it go?”

Additional research should also look back at the environment in which Natovenator lived. “There is a real question of, OK, you’ve got a swimming dinosaur in the desert, what’s it swimming in?” Hone said. “Finding the fossil record of those lakes is gonna be tough, but sooner or later, we might well find one. And when we do, we might well find a lot more of these things.”

In addition to biomechanical studies that will test how Natovenator and related water-dwelling species moved around, studies of geochemical clues in the dinosaur’s teeth and bones, will either confirm or challenge the idea that Natovenator was as strong a swimmer as the study suggests.