In our solar system neighborhood, there’s one planetary family that we haven’t met properly: the ice giants, Uranus and Neptune. Thanks to Voyager mission flybys, we’ve said hello and we know their faces—but we’ve never stopped over for a visit. Now, planetary scientists have decided to make long-overdue plans to walk over and ring the doorbell for a house tour.

The 2022 Planetary Science Decadal Survey, an influential document for planning future missions run by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, recommended NASA prioritize sending an orbiter and probe to Uranus in the coming decades. Past decrees from this process have launched some of the most exciting projects of the 2020s, including the Mars Sample Return and the upcoming Europa Clipper mission.

With eight planets and countless smaller rocks to explore in our solar system, how could planners possibly settle on a single destination—especially when that decision involves millions, or billions, of dollars and affects hundreds of careers? In a recent commentary for Science, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab planetary scientist Kathleen Mandt argues why Uranus is the right choice—and other researchers seem to agree.

“We’ve sent missions to every other planet, to comets, to asteroids, and to trans-Neptunian objects. We’ve sent missions out of the solar system and to the surface of the sun…. Uranus and Neptune are the enigmas of the solar system,” says Will Saunders, an astronomer at Boston University who studies Uranus’s atmosphere.

Humanity’s last up-close glimpse of Uranus, and its sibling ice giant, Neptune, was back in the 1980s with the Voyager probes. Although Neptune would be nearly equally scientifically interesting—its captured Kuiper Belt Object moon, Triton, is of particular curiosity due to its icy volcanoes and more—the extra billion miles to that planet was the dealbreaker.

“The main reason that we chose Uranus first is because it is easier to get to,” Mandt tells Popular Science. “And we have already waited more than three decades for a mission to these planets. Going to Uranus first means less risk and a mission that can arrive at the planet sooner.”

For a planetary mission, “soon” means within the next few decades—the trip to Uranus takes 10 to 15 years, and engineers still need to design and build the spacecraft. As of now, the plan is to launch by 2032, hopefully reaching Uranus by the mid-2040s. The mission would have two parts: an orbiter, which would circle the planet for at least five years, and a probe to dive into the clouds and collect information about the Uranian atmosphere.

Some key measurements that astronomers have for Jupiter and Saturn are still missing for Uranus, such as the amount of noble gases and the ratio of different types of nitrogen. The probe will measure these chemical markers because they’re fingerprints of how and when the planet formed. “The formation of the four giant planets and the way they moved to new locations had a major impact on the whole solar system,” says Mandt. This planetary rearrangement “may be how we got water on Earth,” she adds, and that motion launched many of the objects in the Kuiper Belt and Oort Cloud to their current positions.

[Related: Expect NASA to probe Uranus within the next 10 years]

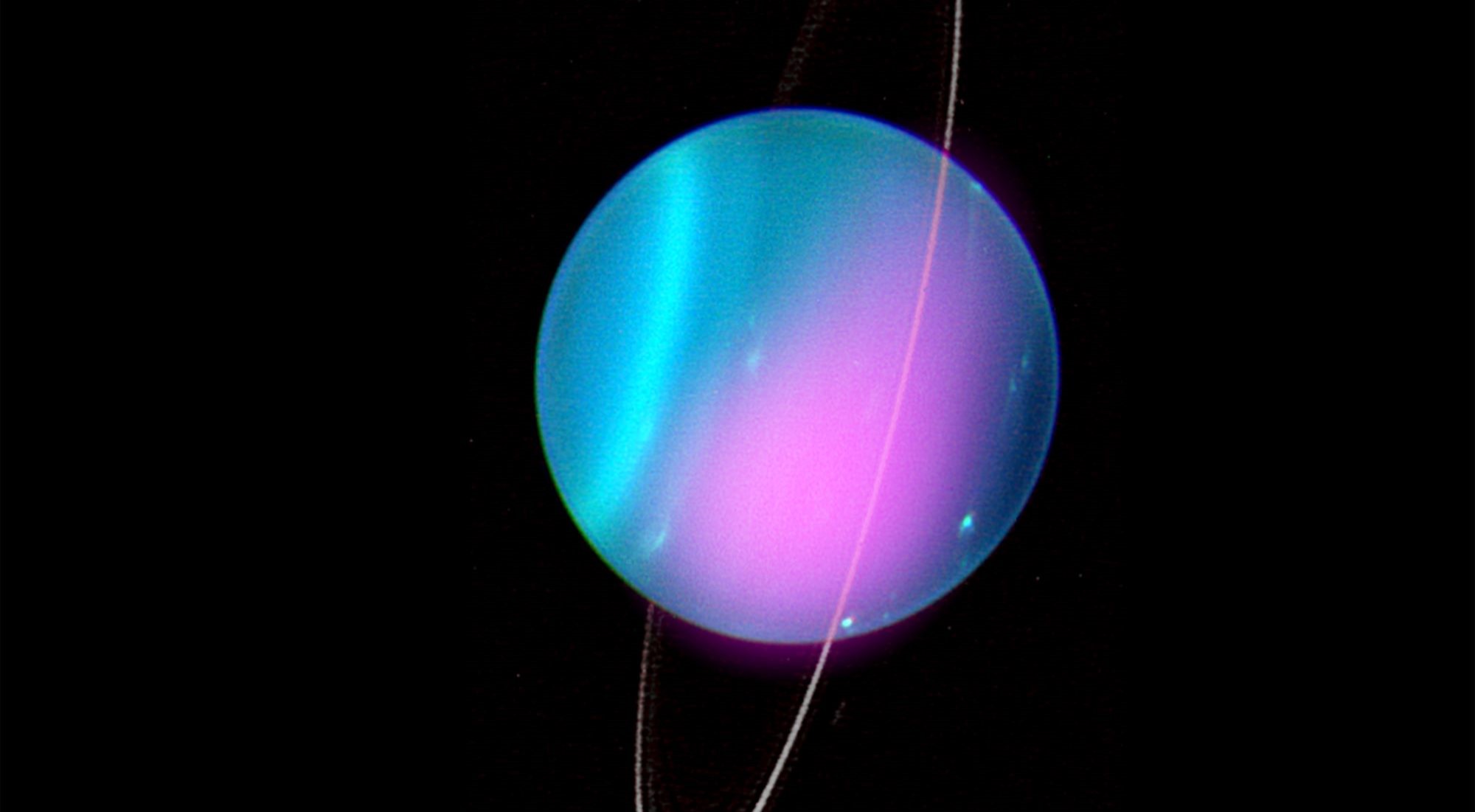

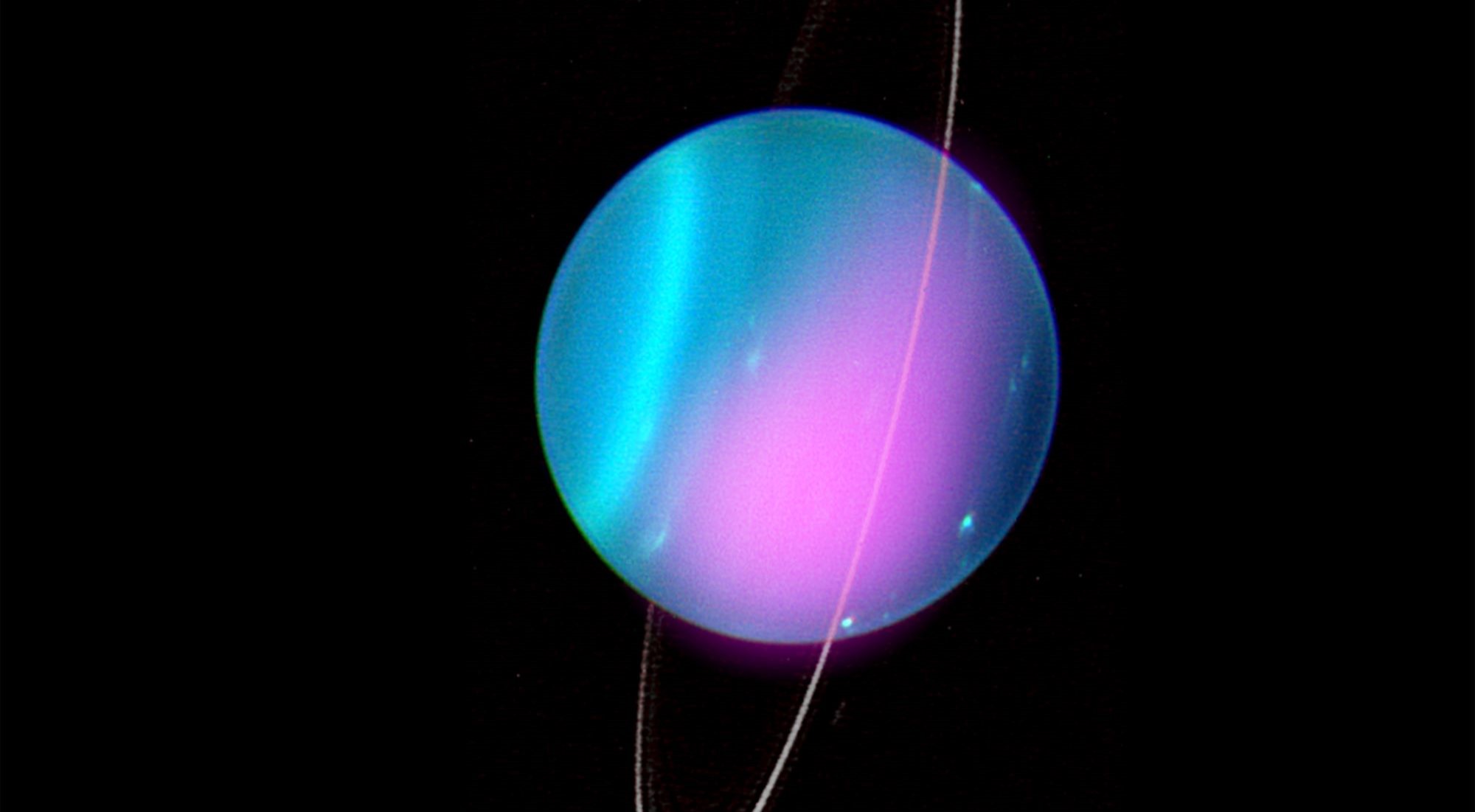

Plus, Uranus is the only planet fully knocked on its side: It’s tilted 98 degrees, which is wild compared to Earth’s 23-degree angle. That causes some quirks in its atmosphere. Planetary scientists are puzzled by the resulting patterns of clouds and wind on Uranus, which they hope to resolve in this mission.

Uranus also has 27 moons, some of which may host oceans below their thick icy surfaces. Subsurface oceans are, of course, one of astrobiologists’ favorite targets for extraterrestrial life, and the satellites of Uranus are no exception. One of the major surprises from Voyager was that Uranus’s five largest moons—Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon—weren’t “cold dead worlds,” as Mandt describes in the article, but were instead geologically active.

“Simply put, I want another picture of Miranda before I die,” says Adeene Denton, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. “Miranda is, to me, one of the coolest and most unusual places in the solar system, covered in geologic terrains we haven’t seen anywhere else.”

The lessons from Uranus aren’t bound to our solar system, either. In the past few decades, exoplanet astronomers have found that Uranus-sized worlds may be the most common type of planet out there. An up-close study of our local example will be invaluable for astronomers trying to understand distant exoplanets—particularly helpful will be determining properties of Uranus’s core and internal structure, such as whether it’s made of rock or ice.

[Related: Uranus blasted a gas bubble 22,000 times bigger than Earth]

“We have not seen Uranus up close since before I was born. That was before we knew about the existence of exoplanets,” says University of Bristol astronomer Hannah Wakeford. “This mission to Uranus is going to change our understanding of our solar system, and planets across our galaxy.”

The upcoming Uranus orbiter and probe mission has the potential to be a revolutionary event in science, bringing our understanding of the ice giants up to par—doing what Cassini did for Saturn and Juno for Jupiter. “An orbiter is really what we need to do profound science that characterizes the entirety of the Uranian system,” says Denton. “There is so much to see and do, and committing to an orbiter is really truly worth it.”

Plus, it will return incredible images of the edges of our solar system, certain to excite and inspire future scientists and space fans. Whenever NASA comes knocking, it always packs cameras, and this meet-and-greet is no exception.