What’s the weirdest thing you learned this week? Well, whatever it is, we promise you’ll have an even weirder answer if you listen to PopSci’s hit podcast. The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week hits Apple, Anchor, and everywhere else you listen to podcasts every-other Wednesday morning. It’s your new favorite source for the strangest science-adjacent facts, figures, and Wikipedia spirals the editors of Popular Science can muster. If you like the stories in this post, we guarantee you’ll love the show.

FACT: Dinosaur sex might’ve been simpler than we thought

By Dustin Growick

Listen. We’re not quite sure how dinosaurs literally came together to make more dinosaurs…but there are some pretty wild theories out there. Did male T. rexes use their tiny arms to tickle the backs of the females while mating? Probably not. Did giant long-neck sauropods—the largest animals to ever walk the face of the Earth—have to go to “sex lakes” in order to breed? Come on now. One thing we’re pretty sure about—based on modern reptile and bird corollaries—is that dinosaurs had cloacas. What’s a cloaca? Well, it’s kind of like one hole to rule them all, out which comes pee, poop, and the sexytime juices. So, yes, like most modern birds, dinosaurs probably practiced a “cloacal kiss” in order to reproduce. How romantic!

FACT: The Monty Python “silly walk” can be great exercise

By Rachel Feltman

The 2022 holiday issue of the British Medical Journal had a real Christmas cracker of a study: An investigation into the biomechanical implications of the Monty Python “silly walk.”

This actually isn’t the first time the silly walk has shown up in peer-reviewed literature. In 2020, Dartmouth researchers published an analysis of the gaits of the two silly walkers—dubbed Putey and Teabag in the sketch—for the journal Gait and Posture. They basically measured how much variation between steps there was, and unsurprisingly found that both were way more variable than a normal gait, but that Teabag’s was much more so than Putey’s.

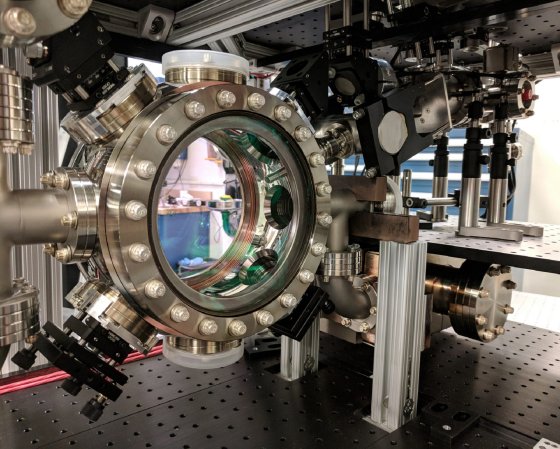

Researchers from the University of Virginia, Arizona State University, and Kansas State University took things a silly step further in this new BMJ paper. They gathered 13 healthy adults and had each of them put on a rig to measure how much oxygen they were taking in, how much energy they were expending, and how intensely they were exerting themselves. Each of them first walked around in a normal gait, then tried to mimic Teabag and Putey.

The scientists found that while the Putey walk didn’t expend much more energy than a normal stroll, the Teabag walk basically amounted to intense exercise.

Based on their findings, the researchers say that doing the Teabag silly walk for 11 minutes a day could provide adults with their recommended amount of physical activity.

Even if someone can’t or doesn’t wish to kick their legs into the air and shuffle strangely for a dozen minutes or so a day, the researchers point out that the key is that the movement is inefficient, from an energy expenditure standpoint. Anything that makes movements less efficient—like traveling in a zigzag—can accomplish the same goal. And since the best physical activity is whatever activity gives you joy to do, a silly walk could sometimes be better than the gym!

FACT: Two ground-shaking discoveries were recently found in old museum cabinets

By Sara Kiley Watson

As someone who doesn’t clean their desk out often enough—do it more often. Especially if you happen to work at a museum. For two museums, the finds in the back of their cupboards were game changing. Researchers found both a hidden lizard relative that holds the key to when squamates originated and the remains of the last Tasmanian tiger on the planet.

When it comes to the lizard, scientists at the Natural History Museum in London originally thought a unique fossil belonged to the Clevosaurus family, a part of the Rhynchocephalia group. These guys only have one living relative, the tuatara of New Zealand, and the oldest fossils go back to the Middle Jurassic, some 238 to 240 million years ago. These guys split from squamates, which includes most of today’s lizards and snakes, way back then. Scientists decided to take a closer look at the fossil, doing x-ray scans and reconstructing the skeleton in 3D, and discovered that this wee lizard has more in common with the ones scampering around your backyard than the unique Tuatara—pushing back lizard evolution as we know it quite a bit before we thought.

The next reason to clean out your old drawers comes from the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) in Hobart, Tasmania. And while these remains aren’t millions of years old, they are still a big deal. For 85 years, the remains of the last known Tasmanian tiger or thylacine were missing—until they were found recently in a museum cupboard. This means the well-photographed “last Tasmanian tiger” wasn’t the last one at all.