A key to lizard evolution was buried in a museum cupboard for 70 years

The sharp-toothed specimen could show the much-earlier origins of the modern lizard.

A new fossil find in the United Kingdom is a victory for de-cluttering and organization enthusiasts everywhere.

The fossil specimen of an ancestor of present day lizards first unearthed in the 1950s was recently found stored in a cupboard at the Natural History Museum in London. The discovery potentially shows that today’s lizards likely originated in the Late Triassic period (about 200 million years ago) and not during the Middle Jurassic as previously believed.

[Related: A Scottish fossil is helping scientists fill the gaps in the lizard family tree.]

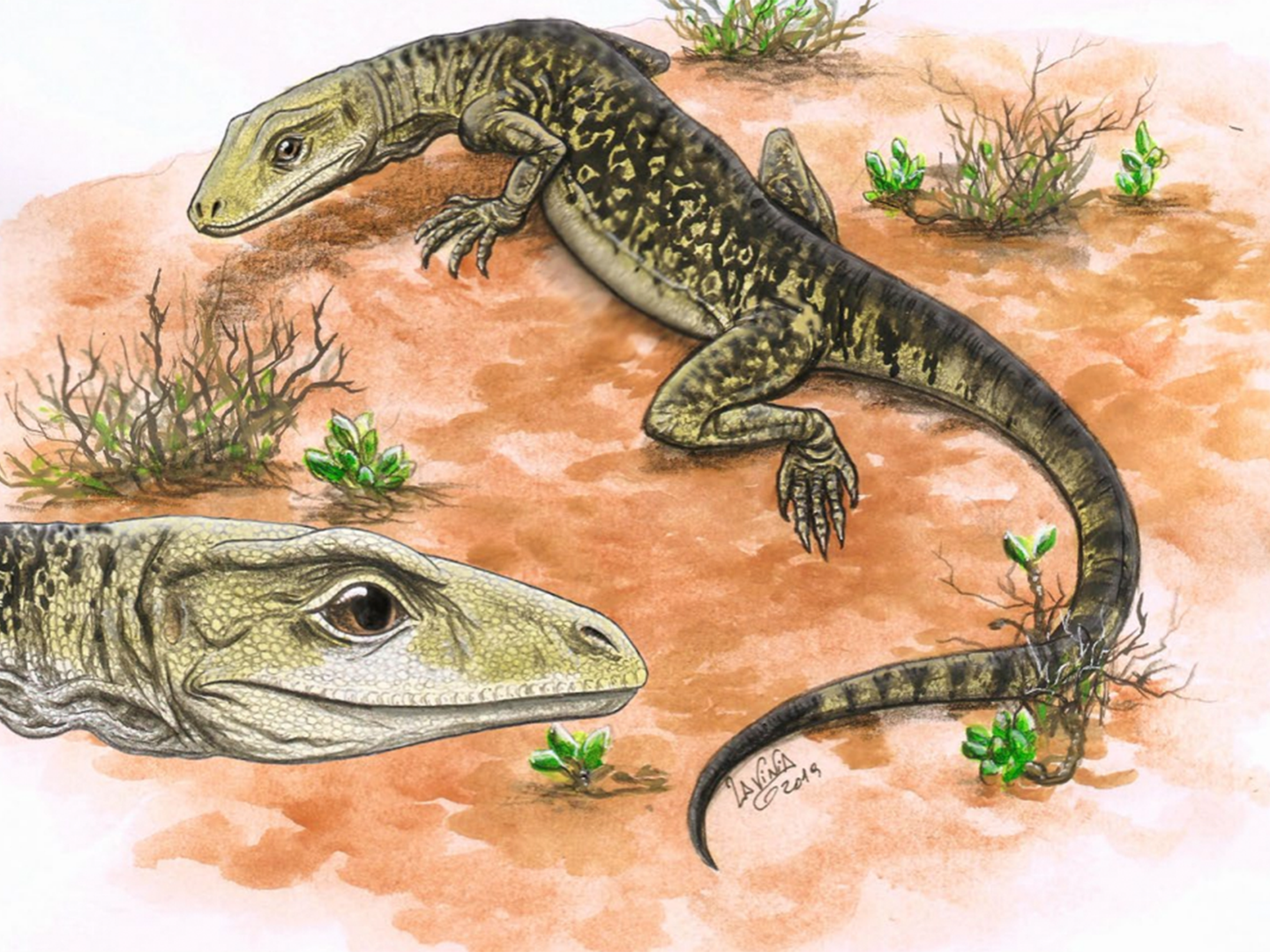

The findings are described in a paper published today in the journal Science Advances. The team named their discovery Cryptovaranoides microlanius, which means meaning “small butcher,” as a tribute to the animal’s jaws filled with sharp-edged slicing teeth.

“I first spotted the specimen in a cupboard full of Clevosaurus fossils in the storerooms of the Natural History Museum in London where I am a Scientific Associate,” said David Whiteside, from the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences and a co-author of the paper, in a statement. “This was a common enough fossil reptile, a close relative of the New Zealand Tuatara that is the only survivor of the group, the Rhynchocephalia, that split from the squamates over 240 million years ago.

The specimens were originally unearthed from a quarry in southwest England.

“Our specimen was simply labelled ‘Clevosaurus and one other reptile.’ As we continued to investigate the specimen, we became more and more convinced that it was actually more closely related to modern day lizards than the Tuatara group,” Whiteside added. “We made X-ray scans of the fossils at the University, and this enabled us to reconstruct the fossil in three dimensions, and to see all the tiny bones that were hidden inside the rock.”

The age of the new fossil impacts the general estimates of when Squamata, the order of reptiles that includes lizards and snakes, evolved, how quickly they evolved, and even what triggered the general origin of the order.

The study shows that Cryptovaranoides is clearly a squamate due to multiple features including its braincase (which encloses the brain), neck vertebrate, upper median tooth in front of the mouth, and the way that the teeth are set on a shelf in the jaws. It also has features seen in more primitive squamates, including an opening on one side of the end of the upper arm bone (the humerus) where a nerve and an artery pass through and few rows of teeth on the bones making up the roof of the lizard’s mouth.

[Related: These tiny ‘dragons’ flew through the trees of Madagascar 200 million years ago.]

“In terms of significance, our fossil shifts the origin and diversification of squamates back from the Middle Jurassic to the Late Triassic,” says co-author Mike Benton a palentologist also from the University of Bristol, in a statement. “This was a time of major restructuring of ecosystems on land, with origins of new plant groups, especially modern-type conifers, as well as new kinds of insects, and some of the first of modern groups such as turtles, crocodilians, dinosaurs, and mammals.

Adding in older modern squamates help complete this evolutionary picture as the Earth rebuilt after the end-Permian mass extinction, which killed about 95 percent of the Earth’s marine species and 70 percent of land species about 252 million years ago.

“The name of the new animal, Cryptovaranoides microlanius, reflects the hidden nature of the beast in a drawer but also in its likely lifestyle, living in cracks in the limestone on small islands that existed around Bristol at the time,” Sofia Chambi-Trowell, co-author and PhD research student at the University of Bristol said in a statement.