Scientists have identified an extremely rare fossilized dinosaur embryo in an egg from southern China.

The late-Cretaceous specimen belongs to a group of dinosaurs called oviraptorosaurs, which are closely related to birds. Intriguingly, the embryo’s position resembles the “tucking” posture that modern birds assume before hatching. The findings indicate that this important adaptation evolved before birds split off from other dinosaurs, the researchers reported on December 21 in the journal iScience.

“Dinosaur embryos are key to the understanding of prehatching development and growth of dinosaurs,” Fion Waisum Ma, a PhD student in paleobiology at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom and coauthor of the findings, said in an email. While fossilized dinosaur eggs are abundant, however, embryos are much harder to come by. The dinosaur embryos that paleontologists have found are usually incomplete, with bones that have separated and become jumbled.

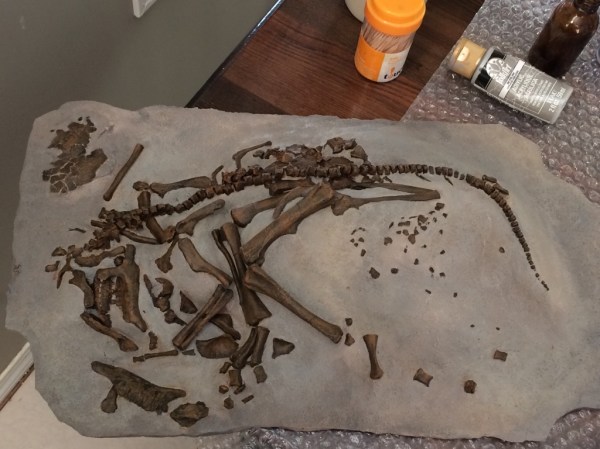

By contrast, the newly described fossil includes an almost complete skeleton with bones arranged much as they were in life. “This little dinosaur is beautifully preserved in a fossilized egg,” Ma said. “We suspect the egg was buried by sand or mud quickly enough that it was not destroyed by processes like scavenging and erosion.”

She and her colleagues were able to reveal more than half the skeleton, with the rest still covered by rocky material in the egg. The fossil, originally discovered in an industrial park in China’s Jiangxi Province, dates to roughly 71 million to 65 million years ago. The elongated egg is 16.7 centimeters (6.6 inches) long and 7.6 centimeters (3 inches) wide, while the skeleton curled inside has a total length of 23.5 centimeters (9.3 inches).

[Related: A newfound South American dinosaur had a tail like a war club]

Oviraptorosaurs have been found in present-day North America and Asia. This dinosaur family is known for its diverse variety of skull shapes, including some with very tall crests. Had the embryo hatched, it probably would have grown into a medium-sized oviraptorosaur, Ma said, perhaps reaching 2 to 3 meters (6.6 to 9.8 feet) in length. The dinosaur would have been covered in feathers and had a toothless skull.

The researchers compared the embryo’s anatomy with that of other oviraptorosaurs and theropods, the broader category of carnivorous dinosaurs that also includes Tyrannosaurus rex. The researchers also examined a fine slice of eggshell under the microscope and analyzed the evolutionary relationships among oviraptorosaurs to determine where the new embryo fell on the family tree. They concluded that the embryo belonged to a subgroup of oviraptorosaurs called Oviraptoridae.

“The most surprising observation is the posture of this specimen—its body is curled with the back facing the blunt end of the egg, [and] the head below the body with the feet on each side,” Ma said. “This posture has never been recognized in a dinosaur embryo, but it is similar to a close-to-hatching modern bird embryo.”

To prepare for hatching, bird embryos reposition themselves in a process known as tucking. The oviraptorid fossil Ma and her team examined is arranged much like a 17-day-old chicken embryo in the first, or pre-tucking, phase. Over the next three days, a chicken embryo would gradually move into the final tucking posture, in which the body is curled with the head under the right wing. This posture seems to stabilize and direct the head while the bird cracks the eggshell with its beak, Ma said.

She and her colleagues suspect that several previously discovered oviraptorid embryos are also arranged in various phases of tucking, although it’s hard to be certain because those specimens aren’t as well-preserved. Still, the team concluded that oviraptorids and modern birds may have used a similar strategy to maximize their chances of hatching successfully, unlike their more distant cousins such as the long-necked sauropods and living crocodilians.

[Related: Whoa, dinosaur eggs looked more dope than we thought]

“Tucking behaviour was usually considered unique to birds, but our new findings suggest that this behaviour could have existed and first evolved among theropod dinosaurs—the ancestors of modern birds,” Ma said.

To confirm this possibility, however, researchers will have to unearth more fossilized embryos of theropods and other kinds of dinosaurs to compare with modern birds and crocodiles. Ma and her colleagues also plan to investigate the skull and other body parts of this embryo still hidden within the rock.

“We hope to answer more questions about dinosaur early development and growth with this exceptional specimen,” she said.