For the past 150 years, paleontologists have warred over the ultimate dinosaur question; were dinosaurs quick, warm-blooded (endothermic) animals or ponderous cold-blooded (exothermic) ones? It’s a question that could be very simply answered by applying a thermometer to a living dinosaur, but there hasn’t been one of those around for approximately 65 million years, and taking a dinosaur’s temperature is almost certainly a difficult endeavor.

So how to resolve the debate? In a paper published today in Nature Communications researchers announced a way to take the temperature of dinosaurs that have been dead for millions of years: look at the eggshells they left behind.

Eggshells are made from calcium carbonate, a hard brittle substance that comes in subtly different variations. In this case, the researchers were looking at calcium carbonate that contained the isotopes carbon 13 and oxygen 18, which both have extra neutrons in their atomic structure, making them slightly heavier.

Even though modern birds and reptiles are separated from their dinosaur predecessors by millions of years, their eggshells are still built in roughly the same way. A female’s body ovulates at a certain time, and forms a shell of calcium carbonate inside an organ called the oviduct. In animals with colder body temperatures, the heavy isotopes cluster or clump closer together in the eggshell, and in animals with warmer body temperatures, the isotopes are spread further apart. The researchers used a similar method a few years ago to estimate dinosaur temperature using teeth.

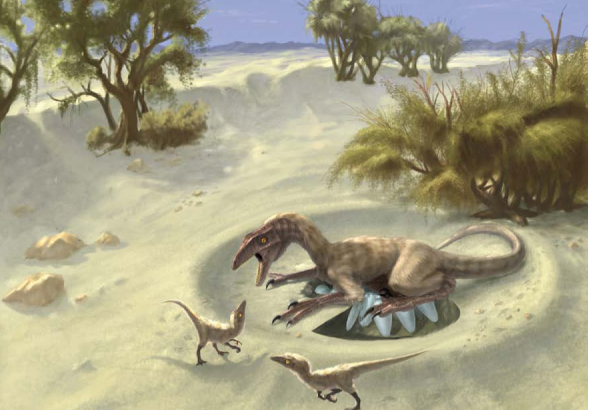

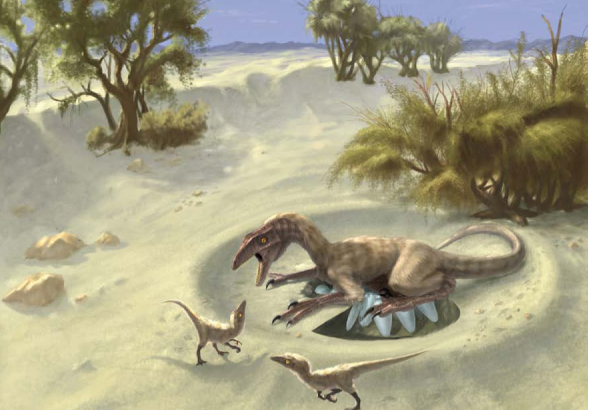

By analyzing modern eggshells, whether the eggs are from quails or giant tortoises, the researchers found they could accurately predict the body temperature of the animal that laid the eggs. After analyzing the egg-laying temperature of 13 birds (warm-blooded) and 9 reptiles (cold-blooded), they decided to put their method to the test with the eggshells of fossilized dinosaur eggs. They found that eggs from giant, long-necked sauropod dinosaurs formed at temperatures of roughly 100 degrees Fahrenheit, while eggs from smaller theropods called oviraptors formed at temperatures of just 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

When they looked at the dirt and rocks directly around the fossils, they were able to determine that the temperature in the environment near the oviraptor fossils (in Mongolia’s Gobi desert) was 79 degrees Fahrenheit around the time the dinosaurs were alive. The dinosaurs were warmer than that, but only just.

“This could mean that they produced some heat internally and elevated their body temperatures above that of the environment but didn’t maintain as high temperatures or as controlled temperatures as modern birds,” lead researcher Robert Eagle said in a statement. “If dinosaurs were at least endothermic to a degree, they had more capacity to run around searching for food than an alligator would.”

It isn’t the last word in a long-standing paleontological debate, but it does suggest that the best way forward might not be warm or cold, but somewhere in between.