Perhaps the most amazing thing about fossils is that they don’t just show us what extinct animals looked like, they can also reveal how those animals lived. Even a fossilised dinosaur egg can provide a wealth of clues about its parents’ behaviour.

Dinosaur hunters in the Javkhlant region of the Gobi Desert in Mongolia recently discovered 15 exceptionally well preserved clutches of eggs that came from a species of theropod dinosaur. Through some fantastic detective work, the researchers argue that this fossil site provides the strongest evidence yet that such dinosaurs nested in colonies and protected their eggs.

I’m a behavioural ecologist. I study how animals live their lives and how species fit together in ecosystems. We can uncover the behavioural ecology of past species and ecosystems by using fossils and our knowledge of animals and habitats today. In this case, I suggest that these dinosaurs may have protected their eggs as a community rather than caring solely for their own nests. It is also possible that these dinosaurs didn’t need to care for their young once they had hatched.

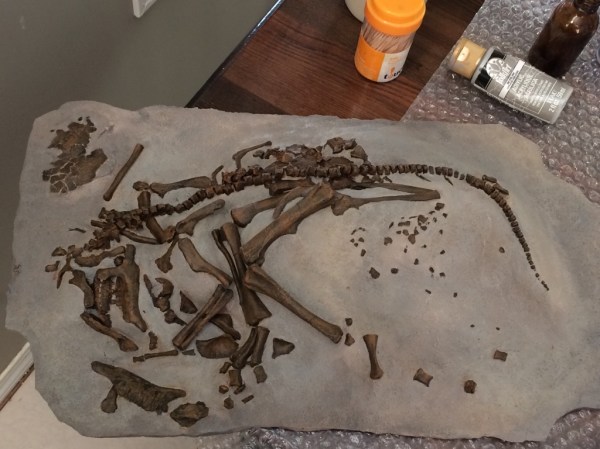

The spherically-shaped eggs were found in clutches of between three and 30 eggs in what was a seasonally arid flood plain. They were laid towards the end of the Cretaceous period around 66m years ago, not long before the dinosaurs disappeared.

The eggs are between 10cm and 15cm in diameter, similar in size to those of the largest living bird species, the ostrich. By comparing the eggs with fossilised embryonic remains in other eggs, the scientists identify that these specimens likely came from the Therizinosauroidea family.

The shells of the eggs have a high porosity, meaning they contain lots of tiny holes. The researchers looked at how this compares to the eggs of living species. We know these dinosaurs lived in a dry, arid environment, and animals in these habitats (such as ostriches) typically lay eggs with few pores in order to minimise water loss.

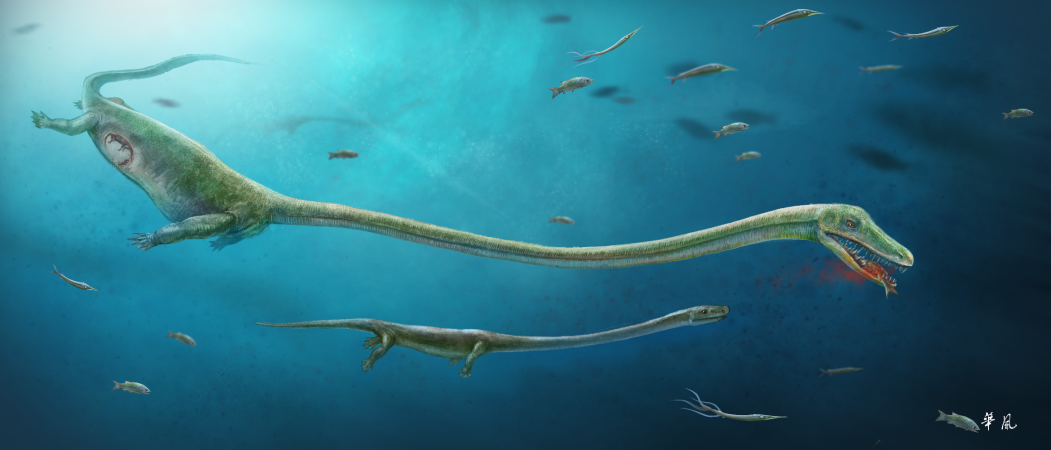

Instead, the high porosity of the Javkhlant eggshells is similar to those of Australasian megapode birds such as the mallee fowl, and crocodilians. These species cover or bury their eggs in organic-rich material, which generates heat as it rots, in order to incubate the eggs. The high porosity of the Javkhlant eggs suggests these dinosaurs did the same because the pores would have made it easier for the developing embryo to breathe in the damp, oxygen-poor environment of rotting vegetation.

The fossils also indicated that all the eggs were laid and hatched in the same nesting season, providing evidence that the dinosaurs nested in colonies. About 60% of them hatched successfully, a relatively high hatching rate similar to that of modern birds and crocodilians that protect their eggs. This supports the argument that these dinosaurs also looked after their nests.

Evidence for dinosaur parental care most famously comes from a fossil of what was thought to be a mother Oviraptor found sitting on a nest of eggs. New understanding of dinosaur skeletons suggests this “Big Mama” should actually be renamed “Big Papa”. Male (paternal) care may have been the ancestral form of parental care, with birds evolving from theropod dinosaurs (birds are avian dinosaurs). In the most primitive group of living birds (including the ostrich) it is usually the male birds that sit on eggs.

However, in the case of our Therizinoid dinosaurs, we think the eggs were buried, which would mean the parents wouldn’t need to sit on them for incubation. But that doesn’t mean they abandoned the eggs completely.

Modern megapode bird and crocodilian species that abandon or rarely attend their eggs after laying and burying them have relatively low hatching success rates (under 50%) because of predators attacking the nests. But, as we’ve seen, the Javkhlant eggs had a higher hatching rate of 60%.

Communal breeding

If the adult dinosaurs didn’t physically incubate their eggs but did protect the nests at a communal site, this could indicate communal defence of the eggs or communal breeding, whereby individuals provide “alloparental” care for the offspring of others.

However, megapode chicks are superprecocial. This means when they hatch they can survive completely independently and so don’t receive any (post-hatching) parental care. So, while the high hatching success indicates these dinosaurs looked after their eggs, it may be that they didn’t need to protect their young once they did hatch.

Unfortunately, the constraints of the fossil record mean it would be very difficult to find direct evidence of communal breeding and cooperative care in dinosaurs. We would need evidence of more than two adults caring for a single brood, or of one adult caring for more eggs than could be laid in a single clutch.

Whatever future fossil finds serve up, there is no question that they will open more windows of understanding into the behavioural ecology of long-extinct dinosaurs. Our understanding will also be informed, not only by the fossils themselves, but by interpretation of the behaviour of modern species. The behavioural dynamics of dinosaur ecosystems were not so different from those of today.

Jason Gilchrist is an Ecologist, Edinburgh Napier University. This article was originally featured on The Conversation.